Third-year Hawks took flight, and nearly reached the peak

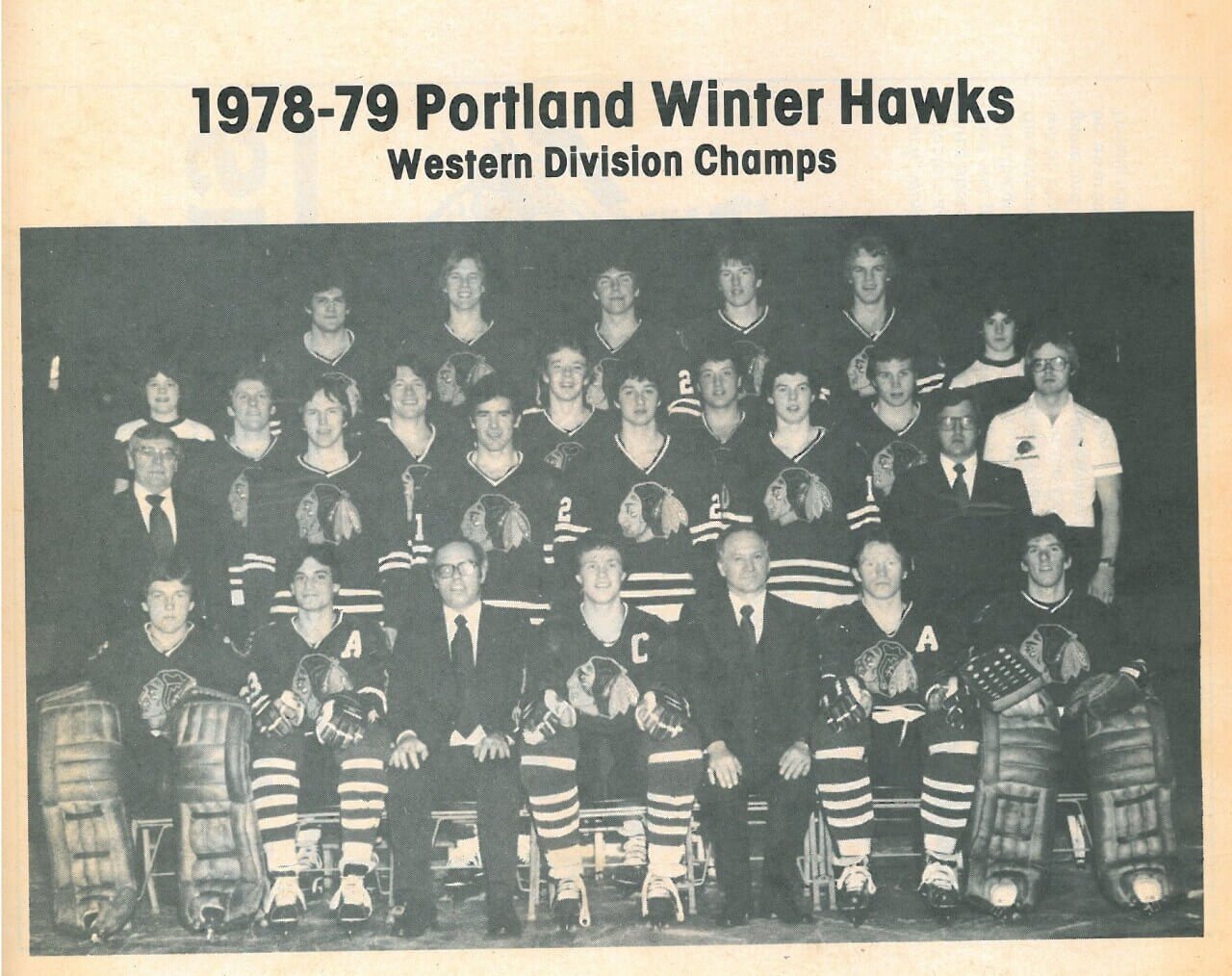

The 1978-79 Winterhawks, who lost in six games to Brandon in the WHL championship series (courtesy Winterhawks)

Updated 1/16/2026 6:38 PM, 1/17/2026 11:18 AM

(The Portland Winterhawks are celebrating their 50th Western Hockey League season. This is second of a two-part series detailing the Hawks’ first three seasons. You can read Part I here. Another recent story on the Babych brothers can be read here.)

After a promising first season in Portland, the Winterhawks were loaded for Bruin, er, bear heading into the 1977-78 season. They appeared to be a team that could challenge New Westminster — which had ousted the Hawks in the West Division finals in the ’77 playoffs — for supremacy in the West Division and, perhaps, in the entire WHL.

The Portland roster was stocked with talented veterans such as forwards Brent Peterson, Wayne Babych, Paul Mulvey, Dale Yakiwchuk and Perry Turnbull and defensemen Larry Playfair, Blake Wesley and Eric Christianson. Rookie Keith Brown, only 17 but brimming with talent, buffed up the blue-line crew. He had been his league’s Rookie of the Year with Tier II Saskatchewan the previous season.

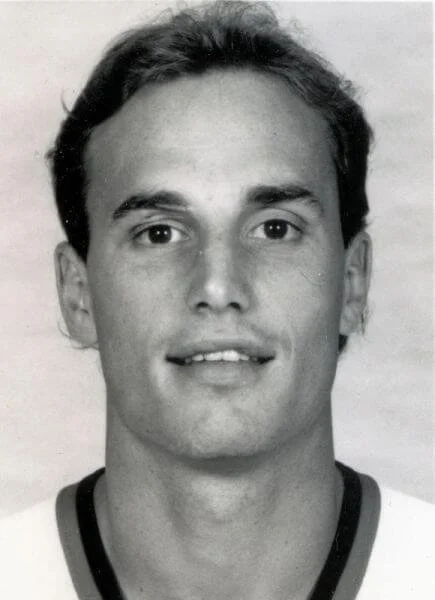

Keith Brown came to Portland as a fresh-faced 17-year-old rookie and left as the WHL’s Defenseman of the Year

“Coming from Edmonton, it was very different, but I loved Portland,” Brown says. “It was an incredible city. I made so many good friends there. We shared an arena with the Trail Blazers. They had just won the NBA championship. I got to watch some of their games. The ‘Big Redhead’ (Bill Walton) was pretty special.”

Rookie forwards Tim Tookey, Ron “Igor” Chorney and Bart Yachimec were ready to help right away. Veteran Jerry Price was acquired from Calgary to divide time in goal with up-and-coming Bart Hunter.

Calgary sent another key piece to Portland — Doug Lecuyer in a seven-for-two trade that also brought the Hawks 15-year-old defenseman Randy Turnbull, Perry’s cousin. (Randy’s greatest claim to fame through three seasons in Portland is that he reigns as the career leader with 1,087 regular-season penalty minutes to go with 236 in 31 playoff games. He might be the greatest fighter in the club’s history.)

Lecuyer, homesick after the team’s move to Portland, had asked for a trade to his native Calgary the previous season. Hodge was open in calling Lecuyer out for what amounted to insubordination. Coach Ken Hodge said then that Lecuyer had reached out to him twice during the offseason to ask if he would take him back.

“This will be his draft year; he feels like he has matured,” Hodge said. “He told me, ‘Anybody is entitled to one mistake.’ ”

Today, Lecuyer explains it this way: “Things didn’t work out in the first season there, and I got traded to Calgary. Growing up is what happened. I don’t know if it was my fault or just a combination of things. I was really happy to be back with them the last season.”

Before the 1977-78 campaign, the Centennials moved to Bighorn and became the Bighorns. The Hawks were the much better team, and Lecuyer made them even better.

“Doug was a very good player,” Brown says. “To be his size in our era, you had to be good with your stick and be willing to use it. That was Dougie. He had an element of being a little bit out there with craziness. He would chop you. He couldn’t fight the giants, but he would do whatever he had to do.”

Brown looked at his veteran teammates for guidance.

“Babych was a WHL superstar,” he says. “Brent was a wonderful captain. He was much more mature than most of us in leadership. Larry was a really solid player and teammate, one of the greatest guys you’ll ever meet. A kind, special guy.”

That’s how Turnbull felt about Brown. Years down the road, Brownie would be best man in his wedding. “Had I not had a small, private wedding, Perry would have been best man in mine,” Keith says.

“Brownie became my best friend,” Turnbull says. “What a player he was. His commitment was so good. He worked so hard, and his skill level was top-notch.”

Brown made an immediate impact as a blue-line regular. Playfair recalls a moment in the preseason, however, when Hodge took him aside, and he realized Tier I hockey was new to his teammate.

“We were doing a drill one day, and every time I would go back and get the puck,” Playfair says. “Hodgie blew the whistle and called me over and said quietly, ‘Larry, how the hell is that kid going to get better if you don’t let him get the puck once in awhile?’ That hadn’t dawned on me.

“But as he matured, Brownie was awesome, way more capable of handling the puck than I was. We played as partners (on defense) a lot of that season. He was a class guy. I loved playing with him.”

Brown was the son of a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police force. He loved his time as a youngster growing up in Edmonton, but had no reservations about coming to Portland to play his major junior hockey.

“My time with the Winterhawks was probably the most enjoyable time I ever had playing hockey,” says Brown, who played 16 NHL seasons, the first 14 with the Chicago Blackhawks. “In the pros, the guys are older and they have families. In junior hockey, you are very young, away from home, and you all have the same goals, desires and dreams — to play in the NHL.

“It was just a fun time for me. Brian (Shaw, the Hawks’ owner and general manager) put together some great teams. We had some real talent during my time there.”

Brown was a finesse player, at 6-1 thin and working toward sinewy. “In training camp my last season,” he says, “I weighed in after Perry. He was like 212 (pounds). I was 172.”

But Brown got bigger during his time in the NHL, bulking up to about 195. He was ahead of his time lifting weights, and he followed the workout routine of Olympic speed-skating champion Eric Heiden.

“I got big-time into doing squats,” Brown says. “When I was 23, I got up to 60 reps at 225 (pounds). I had to get stronger, which makes you faster.”

Jim Dobson, who played with Brown during the 1978-79 season, held great respect for his teammate.

“Brownie was a class act,” he says. “Hard worker. He was one of the first guys who was in shape. He took care of himself, lifting weights. He had the body of a professional athlete. He was dedicated. And he was a good, rah-rah, enthusiastic teammate.”

Brown was a living, skating assist-maker, smart and intuitive in setting up teammates with the puck. He would have fit in superbly with the NHL game today.

“It’s a different world now than what they allowed you to get away with then,” Brown says. “Hockey is so fast today. The players are so talented, but they play with their heads down because they can. They can turn their backs on the boards and not worry about getting run from behind. Those are all great rules to protect the players. It’s a speed and talent game now.”

“At first, Brownie was thin as a pencil,” Mulvey says. “But what a great skater, with superb hands and puck control. I remember somebody tried to roughhouse him in training camp. I didn’t fight the guy, but I stepped in thinking, ‘This guy (Brown) is so good, he doesn’t have to be a tough guy at all.’ He was just a soft-spoken guy and one of our best players right away.”

Entering the 1977-78 campaign, the Hawks’ expectations couldn’t have been higher.

“We thought we had a great shot at winning the Memorial Cup,” Mulvey says, referring to junior hockey’s equivalent to the NHL’s Stanley Cup finals. “Year One in Portland was good, and Year Two was good until the playoffs.”

The Hawks went 8-0 in the preseason, including a 6-4 win at Medicine Hat in which the teams combined for 16 game misconducts and 347 penalty minutes. Despite early injuries to Peterson, Yakiwchuk and Turnbull, they got off to a good start in the regular season.

Shaw would occasionally pop off about opponents through the media. Early in the season, Seattle goalie Gary Nakrayko’s comment about the Hawks playing “dumb hockey” struck a nerve with the volatile Portland GM, who told me for print, “He better watch himself. One of these days one of our players is going to take his challenge — maybe they will take that mask right off him. They should be worried about their own team. They’re in last place, for Christ’s sake.”

A 7-6 win at New West lifted the Hawks to 9-9-4 on the road and 25-12-8 overall past the midway point of the season. Eight Hawks represented Portland in the league midseason All-Star Game — Peterson, Babych, Mulvey, Lecuyer, Turnbull, Playfair, Wesley and goaltender Bart Hunter.

Momentum was building. Actress Jamie Lee Curtis, hot off the release of her film debut “Halloween,” was invited to drop the ceremonial opening puck prior to a home game with New West. Curtis rewarded Bruin captain Stan Smyl with a kiss — and Hawk captain Peterson with two — after which Portland won 6-4 before a record crowd of 7,081.

Afterward, New West coach Ernie “Punch” McLean said the key to the Hawks’ win was their “intimidation of the referee.”

“Happens every time we come down here,” he told me. “They scare the heck out of (the officials). The crap the refs take from Portland — so much stick work. They’re all penalties. It makes me sick.”

Portland stayed hot on the road. Turnbull scored five goals in a 10-3 win at Lethridge on Feb. 24, 10 days after Babych netted five in an 8-2 romp at Victoria. The Hawks edged New West in the regular-season finale to win the West Division with a 41-20-11 record and a franchise-record 93 points. New West and Victoria tied for second, far behind with 77 points. Average regular-season attendance at the Coliseum for the season increased slightly to 3,853.

The Bruins had gone without McLean as coach for much of the second half of the regular season. In February, he clocked referee John Fitzgerald with a punch to the head from his spot on the New West bench in a game at Memorial Coliseum. That earned “Punch” a 25-game suspension carrying through the rest of the regular season. But he was back in the coaching box as the postseason began.

Prior to that, though, there was more chaos as New West came in for a late regular-season matchup at the Coliseum. In the Portland dressing room before the game, Hodge confronted Turnbull at his locker.

“You guys were out again last night,” Hodge told his captain.

“He’s sticking his finger into my chest bone, and he keeps doing it,” Turnbull recalls, “I said, ‘Hodgie, Do that again, it’s on.’ He did it again.

“I shoved him back, and he came back after me. He tripped, fell on my ankle and hit his head against the locker. I was in pain with my ankle. He got up and was bleeding. There was a big chunk out of his head. It was a beauty.”

Things were broken up quickly. A few minutes later, a cleaned-up Hodge returned to the dressing room. Turnbull’s ankle wasn’t in great shape.

“Don’t tell ‘Snuffy’ (Shaw) that this happened,” Turnbull says Hodge told him. “I’m going to tell him you’re injured and not going to play tonight.”

With Turnbull — almost as adept with his fists as with his hockey skills — watching in dress clothes from the stands, a first-period brawl ensued.

“I came down from the stands, got behind the bench and started punching guys,” Turnbull says.

A number of players on both teams were ejected. After the period ended, Turnbull approached Hodge in the dressing room.

“We hardly had any players left,” Turnbull says. “I told Hodgie, ‘Let me suit up. I want to play.’ ”

“Well, I did put your name on the scoresheet,” Hodge said. “You can dress, but I don’t want you going out and doing anything stupid.”

When the remaining Hawks came out to warm up for the second period, Turnbull was with them. Once the fans noticed, they rose to their feet and cheered. They sensed something was going to happen.

“As I started skating, (the fans) started doing the wave,” he says. “It was maybe my most special moment in hockey. They knew I was going to go out and get into one. I got into a fight my first shift, just like Hodgie asked me not to do. I couldn’t help it. The adrenaline took over.”

► ◄

The playoff format that season had the Hawks playing a first-round double round-robin with Victoria and New West, with Portland holding home-ice advantage against both. During the regular season, Portland had gone 5-0-1 against Victoria and 5-0-2 vs. New West in games at Portland’s Memorial Coliseum.

The Hawks won the playoff opener 4-3 over Victoria, but health was a major issue. Peterson, Lecuyer, Turnbull, Christianson and winger Max Kostovich were all sidelined with injuries in Game 2. Portland added three players to the roster, including a 17-year-old forward named Mark Messier. The youngster, who had been with the St. Albert Saints of the Tier II Alberta Junior League through the season, played all seven remaining playoff games for the Hawks, scoring four goals.

Lecuyer remembers Messier when he was 14 and stick boy for a team that had Lecuyer’s two older brothers as players and Messier’s father, Doug, as coach.

“At that age, Mark was about as wide as he was tall,” Lecuyer says. “You could tell he was going to be a brick house. By the time he was 17, you could see it happening for him.”

Mark Messier had taken part in the Hawks’ training camp before the season.

“He rode with me as we drove down from Edmonton to Portland,” Peterson says. “He played in a couple of exhibition games for us. He was unbelievable, already big and strong.”

Doug Messier had ended his played career with six seasons with the Portland Buckaroos from 1963-69.

“We wanted to recruit Mark,” Hodge says. “We wanted him to finish his junior career in Portland.”

The Hawks brought Messier to training camp before the 1978-79 season. Glen Sather, head coach of the WHA Edmonton Oilers, watched an exhibition game in which he played for the Hawks in Alberta. After the game, the Oilers signed him to a contract at age 18. Messier, on his way to a Hall of Fame career, never played a shift of minor league hockey.

“If we’d have had him (in the 1978-79 WHL finals), we’d have had a good shot against Brandon,” Brown says. “He would have been the X factor for us. He actually could have used a season in juniors for his development.”

Messier’s presence couldn’t save the Hawks in the ’78 playoffs, though. They lost their final seven games of the double round-robin and were eliminated. They dropped to 1-5 when the Bruins came from behind for a 5-4 win in Vancouver, B.C., watched by a league-record crowd of 10,987 at Pacific Coliseum. The Hawks’ hopes ended with a 9-2 beatdown at Victoria the following night. During the regular season, Portland had never lost more than two in a row.

“We went in with high expectations but folded our tent pretty early,” Hodge says today. “We had a good club and a strong regular season, but that’s about all I can say.”

Shaw was furious afterward, and I quoted him this way: “We may not go for talent in the future; we’ll go for a little guts and desire. There were a number of our veterans who played without pride and dignity in the playoffs. We were the toughest junior hockey club in (North America); then we became little kitty cats. We weren’t the intimidators; we were being intimidated.”

For sure, injuries played a part in Portland’s demise. Too many penalties led to too many power-play opportunities for opponents. Hunter, who led the league with a 3.88 GAA and an .894 saves percentage during the regular season, had moments of indecision in goal.

“I blame myself for what happened in the playoffs that season,” he says today. “I did not play well.”

Hunter pauses for a minute, then adds, “It’s hard to put a finger on what happened. We just didn’t have it. It wasn’t for lack of effort. It just wasn’t there.”

“That was a letdown,” Babych says. “We had the guys to win. We had injuries, but you don’t talk about that stuff in hockey. Just part of the game. We took it hard. Our fan base was fantastic. We wanted to do better for them. It was such a great place to play.”

“That was a funky playoff scenario,” Playfair says. “Nonetheless, nobody needed to help us lose that series. We lost it on our own. It felt like a step backwards. Instead of progress, we didn’t build off what we had done the season before.”

“If you have a ready-made excuse like you had a bunch of injuries, I guess it’s easier to live with,” Turnbull says. “I was just thinking, ‘I got another year.’ ”

New West — which managed four victories in 14 regular-season meetings with Portland — went on to win its fourth straight WCHL crown and second straight Memorial Cup title.

“It was so disappointing that we couldn’t beat them,” Playfair says. “We had the team to do it. We were big enough. We had everything we needed. They were just a little bit grittier than we were, and when it mattered, they seemed to be able to pull it out.”

In an interview I did with McLean following the Memorial Cup that season, he was kind in his evaluation of the Hawks’ season.

“All season long, they had the worst kind of luck with injuries to key guys,” McLean said. “Those things hurt, and they couldn’t recover. They have a good organization, and they would have been a worthy contender for the Memorial Cup, I’m sure.”

The Hawks had six 30-goal scorers and a dozen 10-goal scorers in the regular season. They also had 10 players with 100 penalty minutes or more, led by Playfair (402), Lecuyer (362), Turnbull (318) and Yakiwchuk (312).

In the June NHL draft in Montreal, six Portland players were selected among the first 30 picks, including Babych who went to St. Louis at No. 3 and was also named first-team all-league for the third straight season. The others: Peterson (Detroit, No. 12), Playfair (Buffalo No. 13), Mulvey (Washington No. 20), Lecuyer (Chicago, No. 29) and Yakiwchuk (Montreal, No. 30).

“I’m sure that hadn’t happened before,” Hodge says. “And with the influx of European players and players from the U.S. colleges, it’s unlikely to happen again.”

So how in the world did the Hawks lose in the first round?

“We get all those guys drafted and we don’t win a (playoff) series,” Mulvey says. “I wish there were a different outcome. I think back and wonder, how do you engage those 25 players to stay focused with eyes on the prize? How much work and love and effort and smarts has to go into it?

“I’m not sure we were trained to do that. No discredit to Ken Hodge. He was a young coach who was thinking, ‘We’re set.’ I don’t know if we lost focus. Ken opened and shut the door, and we didn’t perform. But some of the guidance, that mental performance that you can coax from players, was maybe a little bit lacking.”

A year later, when things turned out far differently for Portland in the postseason, Brown told me this about the 1977-78 Hawks: “We weren’t that much of a team last year. We might have had a winning attitude, but we didn’t have the near the desire. There were a lot of guys who were individuals. That came first, before the team.”

When I read that observation to Brown recently, he quipped, “Hard to believe I had that much brains back then. That would be my quote today.”

Adds Brown: “We were a team of egos. We had such high draft picks. Guys were looking forward to going pro. We were a little undisciplined. Ken tried to get us to play with more discipline. When you have a lot of personalities, that can be difficult. We took a lot of stupid penalties, which really hurt. I don’t think the blame falls at the feet of Ken Hodge.”

Sometime during the 1978-79 season, Hodge revealed to me that he nearly resigned after the previous season. He said Shaw talked him out of it.

“I seriously considered it, not because I didn’t feel I could do a good job coaching, but because I thought a change might be good for the club’s future,” Hodge said then. “Something seemed to be missing, something I wasn’t providing. I knew we had the talent to win the championship. It was not a good time in my life.”

Today, Hodge adds this: “I had decided we had the better players, and we lost. I felt it was my responsibility, that the loss was totally on my shoulders. It should have never happened.”

Hodge, of course, remained on the job, and went on to one of the most storied coaching careers in North American major junior hockey. He remains second on the WHL list with 742 coaching victories.

► ◄

Expectations for the Hawks in 1978-79 were lower after the heavy losses of talent that was evident in the ’78 NHL draft. Victoria and New Westminster appeared to be the teams to beat in the West Division. But Portland had some weapons yet to be unleashed, and plenty of reinforcements.

“When your big guns leave a team — it happens in the NHL — it makes room for the budding young talents to find their way and blossoming,” says Dave Babych, a rookie defenseman and younger brother of Wayne Babych. “Our guys got the space to do that.”

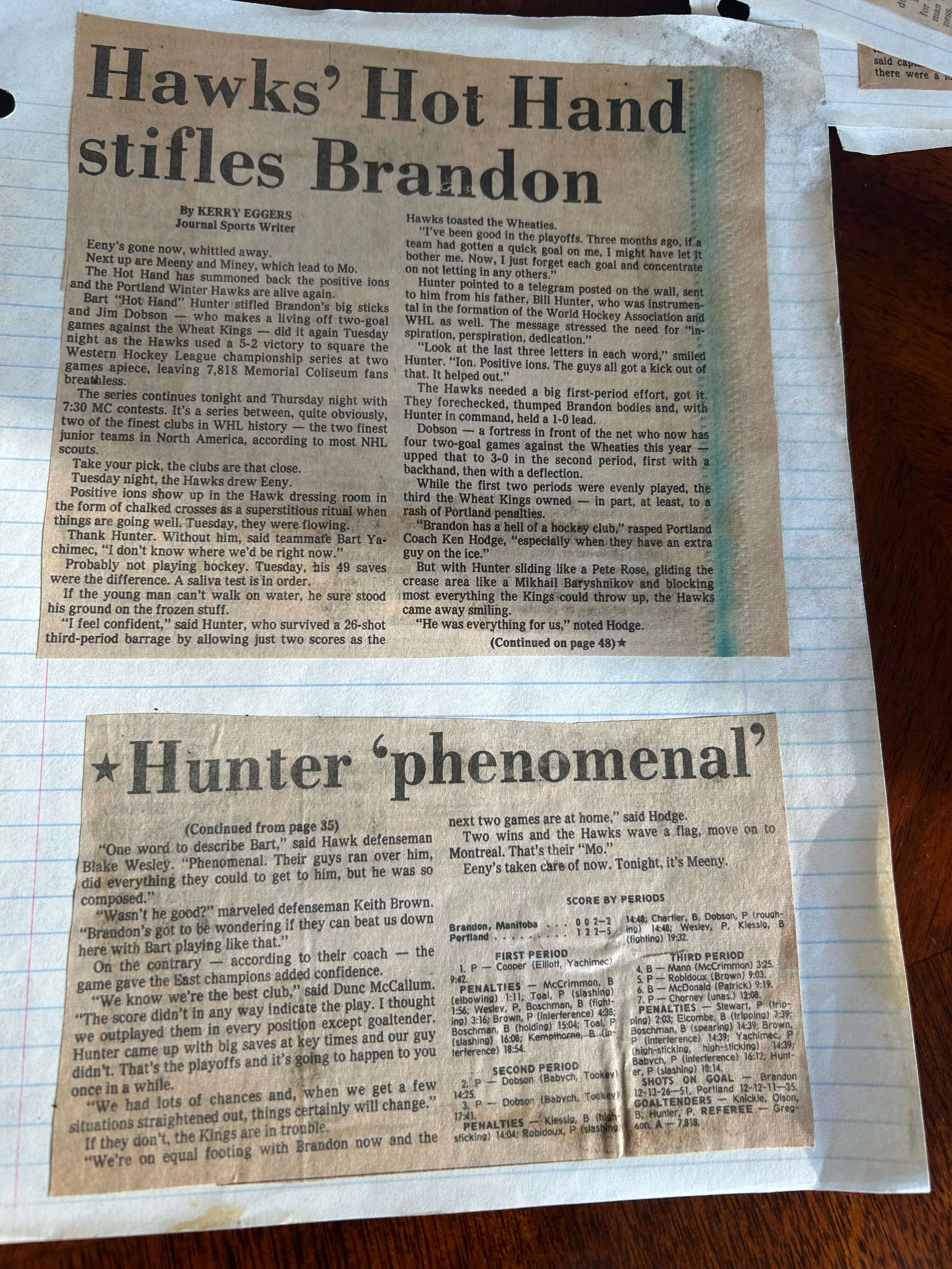

One of the Hawks’ big guns was staying. The fledgling World Hockey Association was offering big contracts to compete with the NHL for talent. Turnbull turned down a three-year, $320,000 offer from the WHA’s New England Whalers to stay with Portland for his final season of junior hockey. Also back was Hunter, the league’s Goaltender of the Year the previous season. He would provide stability and at times sensational play in goal.

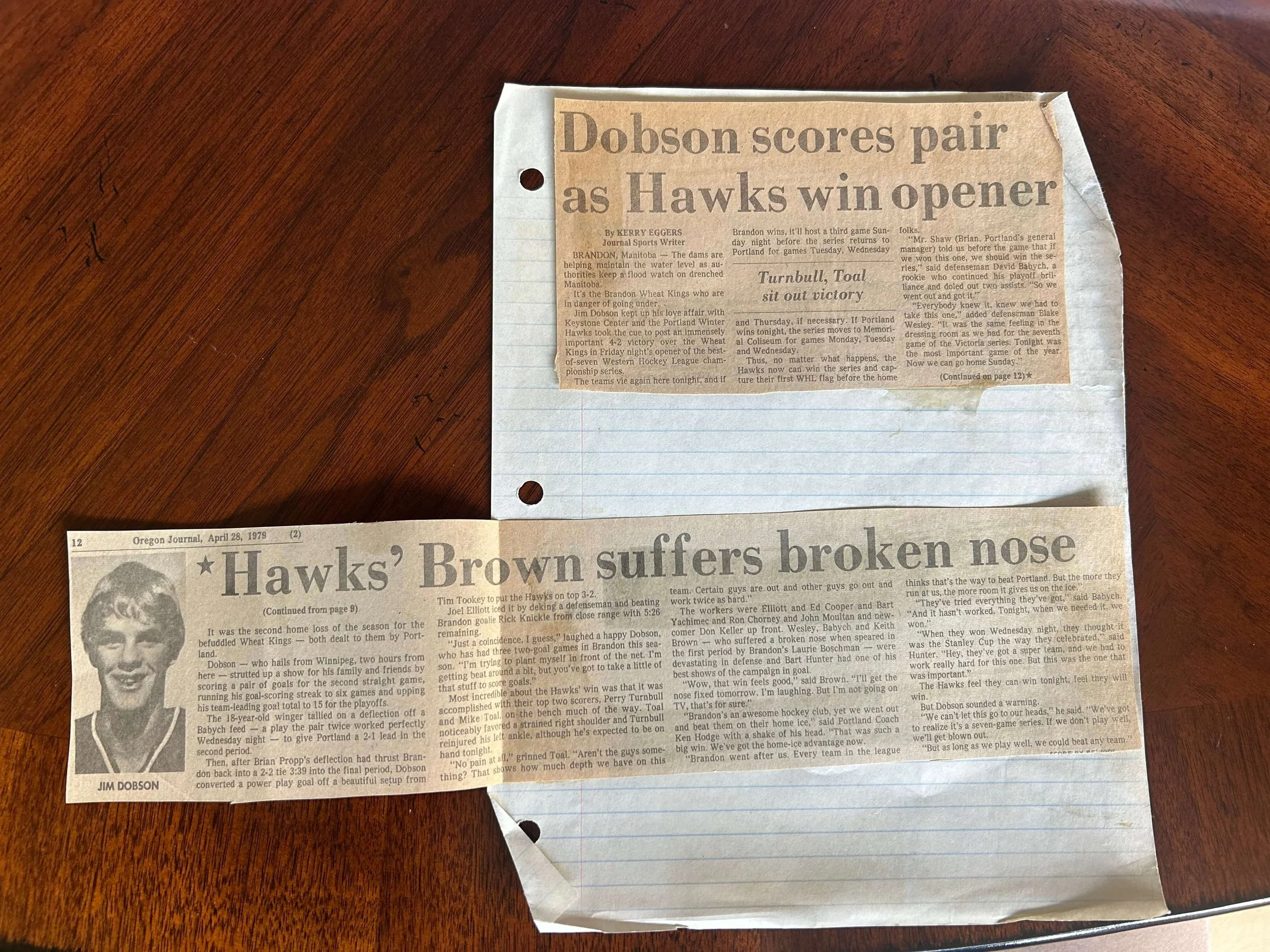

Shaw made a pair of shrewd offseason trades to bolster the roster and thrust Portland into divisional title contention. The Hawks acquired four forwards in the transactions — Mike Toal and Alvin Szott from Billings and Jim Dobson and Florent Robidoux from New West.

“Outstanding deals for us,” Hodge says. “Brian and Wayne orchestrated a number of excellent trades for us, and those were among the best.”

Portland would finish the 1978-79 regular season with a 49-10-13, second-best in the league to Brandon’s remarkable 58-5-9 mark. The Hawks were successful on the road, too; their 19-7-10 mark is one of the best in franchise history. They advanced all the way to the WHL finals, losing to the Wheat Kings in six games.

The Hawks had a WHL-record 10 players score 20 goals or more. Surprisingly, average home attendance for the regular season stayed flat at 3,842, though it picked up as the season wore on and in the playoffs.

The 6-foot, 175-pound Toal centered the first line with Szott and Turnbull with spectacular results. Turnbull scored a franchise-record 75 goals and won the WHL (changed from WCHL before the 1978-79 season) Most Valuable Player award. Toal led the Hawks and was sixth in the league in scoring with 121 points (38 goals, 83 assists). Szott, a 5-10, 160-pound right wing, chipped in 100 points (40 goals, 60 assists).

“Mike was a magician at center ice,” Hunter says. “How many of those goals did Perry flick into an empty net after Toal slid it over to him, and thank you?

“Tookey was super-talented, a very shifty player. As a goalie, he was one of those guys in practice that every day was a challenge. Those guys are fun to play against. Perry was more the up-and-down winger with a good shot. Tookey and Toal were magicians.”

Dobson and Robidoux, playing on the second line with Tookey centering them, combined for 74 goals and 151 points. And Tookey, coming into his own, had 33 goals and 47 assists. Dobson would be a postseason star, too, with 17 goals and 23 points in 25 playoff games.

“Dobber had an energy about him that was contagious,” Dave Babych says. “Robidoux was another good, solid player. They just knew what to do and they fit in well. Management found character guys to fill in the spots to glue the team together.”

Dobson and Robidoux had spent the majority of the previous season at Tier II Abbotsford. Near the end of the 1977-78 regular season, they were called up to the Bruins. Both played what Dobson calls “semi-regular shifts” in the playoffs and helped New West win the Memorial Cup. But Dobson was thrilled to be traded to the Hawks in the offseason, and his two years in their uniform were the favorite of his playing career.

“I’ve always considered Portland the class act of junior hockey,” says Dobson, who makes Portland his home today. “What a great place to play hockey for a young man. The fans treated us like gold. We were like rock stars. We weren’t, but that’s the way we were treated. I knew Portland was a great place to play. Best move I ever had made for me.”

When Dobson played for Abbotsford, he would often attend New West games at Queen’s Park Arena.

“One of the first games I went to was when the Bruins were playing Portland,” Dobson says. “Right in front of the New West bench, Perry just beat the crap out of one of the Bruins. He was bleeding like a stuck pig. And Perry was pointing at players on their bench like, ‘You’re next.’ I thought, ‘This guy is an animal.’ ”

By the time Dobson joined Turnbull in Portland for his final season there, Perry had toned down his act.

“Perry was my favorite teammate through my entire hockey career,” says Dobson, who played 10 years of junior and pro hockey, including parts of five seasons in the NHL. “I respected Perry. I admired Perry. He was such a good player He was tough. He could skate. He could do it all. And he was a very good captain.”

In his first two games facing his old team during the 1978-79 season, Dobson fought New West’s Rick Amann three times. After the second game, I asked him why. “I don’t know,” Dobson told me then. “I lived with him last year. He has always been quite chippy.”

Nearly 50 years later, I ask “Dobber” about it again.

“Funny, because we had the same billet (in New West),” he says. “He just got under my skin. That’s what it was like back then. Trash-talking every game, all game long.

“The game was barbaric in that era. It was crazy. We could go to five Winterhawk games these days and not see a single fight. In those days, if you didn’t see five fights in the first period of a game at Queen’s Park Arena, something was wrong.”

There was bad blood between the Bruins and Hawks, and Dobson was one of the few to experience it from both sides. After the trade to Portland, there was an altercation between Hunter and New West forward John-Paul Kelly, who wore a facemask to protect an eye that had limited vision.

Several players from both sides got involved.

“I came into the pile and just started throwing punches,” Dobson says. “Bart somehow got Kelly’s helmet off. Then Bart put the helmet on and was parading around the ice, acting like a blind man. Ernie (McLean) comes flying out on the ice to confront Bart. It offended Ernie quite a bit, because he had only one eye, too. Then Brian Shaw comes running out to try to calm down Ernie. It was quite the scene.”

Portland had top-end players that season, but front-line role players did their job, too, including the checking line that featured Yachimec (26 goals, 58 points), Chorney (20 goals, 58 points) and Joel Elliott (27 goals, 56 points). Versatile winger Kostovich (29 goals, 56 points) filled in superbly and mixed it up when needed, and rookie Ed Cooper emerged late in the season and through the playoffs.

Portland was strong in defense, led by Brown, who would be named the WHL Defenseman of the Year. Also manning the back end were the veteran Wesley — who would be a second-round draft pick in 1979 and played eight NHL seasons — and rookies Babych and Glen Ostir. Brown finished third in the WHL with a franchise-record 85 assists. Babych, big and tough as nails, contributed 20 goals and 79 points, the latter still a franchise record for 17-year-olds. The next season, he would succeed Brown as the league’s Defenseman of the Year.

Babych tells me now that he felt like he “won the lottery” by getting to play his junior hockey in Portland.

“We got treated really well, like the pros did,” he says. “I know that for a fact. We were treated better — the hockey part, at least — than in Winnipeg, my first (NHL) team. They didn’t hold anything back. It was whatever you needed, within reason.”

Babych, at 6-2 and 220 much bigger than older brother Wayne, would go on to play 20 seasons in the NHL.

“I don’t think there was a stronger guy in the NHL than Dave,” Wayne says.

Part of that was working on the farms of their father and uncle in Edmonton. In their formative years, they worked the farms in the summers and most weekends during the school year.

“We would haul bales of hay or pick rocks, whatever was needed,” Dave says. “When you’re 12 and you have to throw a bale on the top rack, you figure out how to do things. If I’d asked my dad for gloves, he’d have slapped me silly.

“It was healthy for us. It helped our physical fitness. We didn’t think of it as a workout. Wayne was deceptively strong. I never had a problem with strength.”

Hodge can’t remember coaching a stronger player.

“Dave was a man,” Hodge says. “He was so big and strong. One time we played golf together and he left his wristwatch in my golf bag. It had a clasp-type band. I put it on my wrist, closed the clasp and it went straight to the pavement. He was so big and strong.

“We played the (NHL Chicago) Blackhawks in a preseason exhibition in Portland and Tony Esposito was in goal. We had a power play, and the guys kept on passing the puck to Babych, and he would unload a slap shot. Tony was yelling to his teammates, ‘Don’t let him shoot!’ ”

Babych got into very few fights while with the Hawks, “because everybody was afraid of him,” Dobson says. “Nobody would mess with him. The word was, ‘Don’t wake Babych up.’ He was a man amongst boys. He was like a young Shaquille O’Neal. He was a beast. He could hit guys, he could score, he was a very good player.”

Dave laughs when I read him that quote.

“Maybe I fooled them,” he says. Fighting “was Wayne’s job. My mom would give Wayne s**t. ‘Why do you fight all the time? He’d say, ‘Mom, you should hear what they say about you.’ ”

► ◄

The Hawks were put together in a different way than the previous season.

During the 1977-78 regular season they scored 361 goals and had 2,943 penalty minutes, most in the league in the latter category. In 1978-79, they scored 432 goals and had 1,710 penalty minutes, fewest in the league. It was a stark, almost shocking contrast in styles. Did Shaw and Hodge change their philosophy toward how they wanted their team to play?

“There wasn’t a change in philosophy, but we did try to clean up our act and minimize our penalty minutes,” Hodge says. “Every year, you worked with a different group of players, and we had a significant change in personnel.”

“If we were the least penalized team, we certainly did not play that way,” Hunter says. “There was nobody afraid to go in the corner. We held our own. That was never an issue. I never thought we didn’t have guys who were physical. That was not the case.

“The guys came together that season. The core was a year older. We had a fast team, a bunch of good skaters, fluid guys who could get out and wheel and deal and, by the way, we’ll come back and try to play defense once in awhile.”

Turnbull, Hunter says, “was still a tough guy. Opponent knew if they fought Perry, they weren’t going to come out on the right end of it.”

Turnbull had matured as a player, but also as a person. He went from 36 goals and 318 penalty minutes in 57 regular-season games in 1977-78 to 75 goals and 191 penalty minutes in 70 regular-season games in 1978-79. (Perry still ranks second in franchise history with 791 career penalty minutes, behind only cousin Randy.) Add 10 goals in 20 playoff games and it gives Turnbull 85 goals in 90 counting games for the 1978-79 campaign. That still ranks as the second-most prolific season in franchise history, behind only Dennis Holland with 97 goals (82 regular season, 15 playoffs) in 1988-89.

“They put me on the wing with Toal and Szott that year,” Turnbull recalls. “They were skilled and fast, and (opponents) didn’t want to be committing penalties against us. That settled things down. We still had enough toughness that they didn’t want to play that way against us. Most of the tough guys left the league (after the previous season). There weren’t a whole lot of enforcers left.”

The amazing thing about Turnbull’s season was, he played on a gimpy ankle late in the regular season and all through the playoffs.

“I had torn ligaments in the ankle,” he says. “You should have seen how Innes put me together before games. But I wanted to play, anyway.”

“At the end, Perry played with an ankle he could hardly walk on,” Brown says. “I remember seeing him limping badly after games. He was so tough. He struggled with pain all through the playoffs. He never should have been on the ice. Nowadays, he would be out for a couple of months with that ankle.”

Brown neglects to mention the painful injury he played through the second half of that season.

“Brown couldn’t even lift his arm,” Dave Babych says. “He had a bruise on his shoulder and arm that was like a goose-egg. I don’t think he missed a game.”

Brown, who also broke his nose in Game 1 of the WHL finals but played on, says the secret to Portland’s success that season was simple.

“We had very few egos,” he says. “Perry was our superstar and Bart was a great goaltender. We had a lot of good players. We all played roles. There were unsung but important players like (defenseman) Donny Stewart. Not a ton of talent, but boy did he have character. He would do anything for his team. He would put his face in front of a puck. You don’t always get that. He was a special individual.”

Dobson gives the coach credit, too.

“It was good playing for Hodgie,” he says. “He’s a little bit socially inept — most guys would say that — but he was well-organized and calm and collected. He would get pissed off when he had to, but he knew how to handle the bench, push our button when necessary. He did a good job with all of that.”

► ◄

The Hawks went 10-1 in exhibition games and then came out smoking in the regular season. There were 5-0 and 9-3 wins over Seattle and a 11-1 undressing of New West (after the game, Turnbull called it “the most satisfying win in my three years here”) bookending a 5-5 tie with Calgary in which Portland rallied from a 5-5 deficit with 10 minutes left.

Turnbull was on a roll. He scored a pair of goals in a 14-3 dismantling of Lethbridge and a five-spot in a 7-6 triumph over Victoria. Hat tricks in the next two games, including a 12-2 beatdown of Medicine Hat, gave him an amazing 21 goals in 14 games.

“I remember how hard that team worked,” trainer Innes Mackie says. “Hodgie didn’t get back at Christmas time after the break, and Brian ran a practice. He was out there just before they were through for the day, making them skate one end to the other, trying to wear them out. They were just laughing at him. He couldn’t make them quit. They worked their butts off, and got results.”

Dobson, a Winnipeg native, scored a pair of third-period goals to lift Portland to a 3-2 win at Brandon on January 15. It was the Wheat Kings’ first home loss in more than a year and only their second loss in 37 games during the 1978-79 campaign. Shaw called it “the biggest win in the history of the franchise.”

Dobson matched the club record with five goals in a 12-3 rout of Calgary. Dobson’s best friend growing up in Winnipeg was Wranglers goaltender Warren Skorodenski. They exchanged greetings in pre-game warmups.

“I’ll bet you a 12-pack of Labatt’s blue lights that I score on you tonight,” Dobson said.

“You’re on,” Skorodenski said.

Dobson red-lit five on him.

“That summer, when I went back to Winnipeg, he gave me five 12-packs of Labatt’s,” Dobson says. “It was a good deal.”

The Hawks carried a 19-game unbeaten streak into the February 14 rematch in Portland, Brandon got retribution with a 7-4 win before a record crowd of 8,241 despite Turnbull’s ninth hat trick of the season and Portland owning a 54-38 shots-on-goal edge. At that point, Brandon was cruising with a 42-3-7 record.

“I was out on the street the week before the game and people were saying, ‘Brandon is coming to town,’ ” Mackie says. “That’s when I knew we had turned the thing around in Portland.”

The Hawks kept rolling up victories. After the loss to Brandon, they went on a 14-1-2 tear over the next 17 games.

“We’re team-oriented,” Wesley told me then. “We have different guys playing big each night. And we don’t go goofy, eh?”

In an interview late in the regular season, Turnbull said many of the things Brown would say 50 years later, only in even stronger terms.

“This year, we didn’t have the ego guys who question everything Ken tells them, the guys who think they know it all,” Turnbull said. “I’m not going to name names, but there were a few of them last year, and it really hurt us. This year, the guys have gone out and done what Ken has wanted us to do — and generally, it has worked.”

Turnbull scored a hat trick — his 12th of the season — in a 13-2 win over Medicine Hat late in season, breaking Tony Currie’s franchise record for goals. Yet he was upstaged by teammate Elliott, who had four goals in the contest.

The next game proved to be a dark day in franchise history. Portland visited Queen’s Park Arena for the final regular-season meeting between the rivals and the third-to-the-last game before the playoffs. Due to injuries, the Hawks were shorthanded. They dressed only 17 players. Turnbull wasn’t playing.

Four seconds before the end of the game, there was a set-up.

“I looked around and Ernie had his five biggest, toughest players on the ice,” Dobson says. “It was clear what they were going to do.”

New West defenseman Bruce Howes jumped Dobson.

“I got sucker-punched,” Dobson says. “And then their whole bench was coming on the ice.”

During a fight, league rules were the other players on both teams were to skate to the bench, and players on the bench weren’t to come onto the ice. Dobson and Wesley were left on the ice unprotected. Dobson and Wesley got pummeled, seemingly dozens against two.

“They knew what Ernie wanted them to do,” Dobson says. “He wanted them to beat the crap out of us, so we would be hurt and couldn’t play in the playoffs.”

Hunter was in goal when it happened.

“I was down at the far end,” Hunter says. “I was scared to death. Boris Fistric and John-Paul Kelly came toward me. I threw my catching glove off. I had my blocker out and my stick up over my shoulders. I was like, ‘OK boys, if you want to, come on.’

“Somehow, I made it to the bench and they didn’t attack me. I stood in front of the bench and watched. Those guys took a kicking. It was a sad night.”

It was hard for anybody to watch, especially Hodge and his players.

“I know the guys wanted to jump on the ice, and Hodgie kept them back, but I don’t blame him,” Dobson says. “He was smart enough not to buy into Ernie’s plan. I don’t think (Hodge) thought it would get that carried away. Normally you don’t have four or five guys jump in and beat up one guy.”

Two days later, the Oregon Journal ran a photo of Wesley, his face bruised and cut up, his eyes blackened.

“Blake got beat up worse than I did,” Dobson says. “I played in the next game.”

The WHL suspended McLean for the entire postseason. Seven New West players were also suspended, and charges of common assault were filed against them. They returned after a few playoff games, but the Bruins were quickly eliminated. That summer, a judge banned them from playing at any level until December 1.

“The brawl ruined hockey in New West,” Hunter says. McLean stayed on as coach for one more season in which the Bruins went a league-worst 10-61-1. In 1981, the franchise moved to Kamloops, B.C.

► ◄

Heading into the postseason, Hodge told me, “I don’t believe the incident at New West had an overbearing effect on our hockey club. We will dispel that theory by doing well in the first round.”

Portland’s first playoff action was a double round-robin with Victoria and New West, the same format used the previous season. This time, the Hawks were ready. They beat Victoria 5-3 in the opener.

“The last two days, all the guys have been doing is eating, drinking and sleeping hockey,” a mostly recovered Wesley said afterward. “That’s one thing we didn’t do last year. We had other things on our minds. It was too much of a country-club atmosphere.”

Eight Bruins had to sit out Portland’s next game, its first against New West. Kostovich scored four goals to lead the Hawks to a 9-2 rout.

“New West was awful,” Brown said. “This shows that whatever Ernie thought he did last week, it didn’t work.”

Portland went 7-1 in the first round to set up a best-of-seven matchup with Victoria. The teams split the first six games. As the Hawks warmed up before the elimination Game 7, Hunter was emotional and, eventually, in tears. He threw down his gloves, gathered his teammates in a circle on the Coliseum ice, and they held hands and in silence.

“At that moment, you could feel the love the guys have for each other,” Tookey said afterward. “I think it helped get us through this one.”

Turnbull’s tender ankle had forced him to miss Games 4 through 6. After skating in warmups he decided to play and scored the game’s first goal. The Cougars seized a 2-1 lead, but Dobson converted a hat trick and the Hawks finished the game with six straight goals in a decisive 7-2 win.

“In the dressing room, you could feel Perry Turnbull,” Hodge declared after the game. “On the ice, you could feel Perry Turnbull. I think the fans could even feel Perry Turnbull.”

The series victory thrust the Hawks into a double round-robin with the other division champions, Brandon and Lethbridge, with the team with the poorest record in the competition facing elimination. Portland walloped Brandon 10-0 in the teams’ opener, but both teams finished 3-1 to set up a finals showdown.

“I have never been associated with a club that is this coachable, with a group of players who play so close to their potential game after game,” Hodge said of the Hawks as the WHL finals began.

To reward the Portland players for their efforts, Shaw announced that rather than embarking on a 1,300-mile bus ride to Brandon, they would be flying there for the finals.

“Everybody was excited to be flying, and then we see the plane,” Dave Babych says. “It was a WWII bomber, a DC-2 with a small wheel on the back.

“We had to fly to Cranbrook (B.C.), one of the worst airports (in which) to land in Canada, because you have to fly through valleys and there is a lot of turbulence. As we took off from Cranbrook to Brandon, the plane was fishtailing off a cliff at the end of the runway. Once we were up in the air, the wind was blowing us sideways. All the puke bags were pretty much full after that take-off, but we got there safely. Another chapter in the book that year.”

Stomachs settled, the Hawks stole the opener 4-2. Dobson scored two goals, including the third-period power-play game-winner, and Hunter made 38 saves. Portland’s victory meant the first three games would be staged in Brandon, the next three in Portland.

Despite being outshot 42-34, Brandon won 3-1 in Game 2. Dobson, who had tallied six goals in three games in Brandon during the season, was ejected midway through the first period for being third man in an altercation. He pulled the Wheat Kings’ Don Gillen off Hunter after Gillen had speared him.

Brandon edged the Hawks 6-5 in Game 3, scoring three power-play goals in the second period to go ahead 4-0. Turnbull scored two goals over the final 25 minutes, but it wasn’t enough.

With the series moving to Portland, the Hawks got even again at 2-2 with a 5-2 win in Game 4. Dobson scored a pair of second-period goals, his third and fourth of the series, but the Wheat Kings outshot the Hawks 51-35. Hunter registered 49 saves in an epic performance.

“Bart was forced to be a standout,” Hodge said. Added Brandon coach Dunc McCallum: “Hunter was the difference, no doubt about that.”

The Hawks hoped to win the next two games, clinch the series and write themselves a ticket to the Memorial Cup in Quebec. Instead, they lost a pair of heartbreakers.

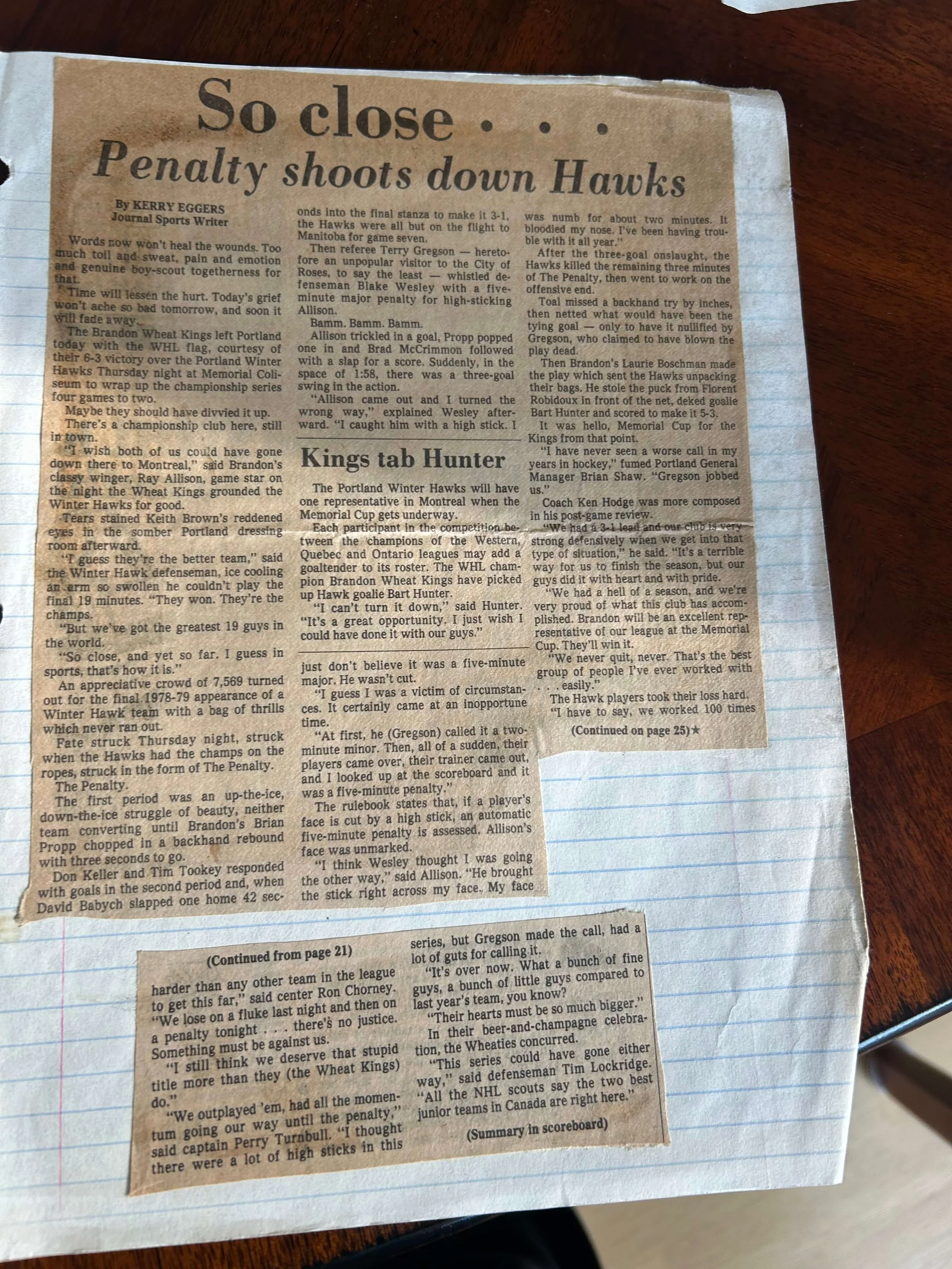

Brandon won Game 5 by a 4-3 count in overtime before a raucous Coliseum throng of 6,677. Portland held a huge 55-27 edge in shots on goal, but Brandon’s Rick Knickle stood on his head, making 52 saves. With the Hawks facing elimination in Game 6, they led 3-1 in the second period. But the Wheat Kings scored three goals after a controversial five-minute high-sticking major to Wesley and went on to win 6-4.

“It was a terrible call,” Hodge said afterward. “I feel sorry for Blake, because he feels so guilty.”

And that was it. After 108 games including exhibitions, Portland had amassed 76 victories with only 19 defeats, but their quest for a league title and Memorial Cup berth had fallen short.

Brown never won a Stanley Cup championship during his long NHL career.

“We came close in Chicago,” he says today. “Went to the semifinals six times and the finals once. We had chances in there, but it was never as close as that year in Portland.

“Brandon was a lot better than us, no question. They had a ton of good players. But our group was special. There were a lot of tears in the locker room. We did not want that season to end. That was the closest team I was on during my entire hockey career.”

Brandon’s first line of Brian Propp, Ray Allison and Laurie Boschman combined for 220 goals and 276 points during the 1978-79 regular season, and another 44 goals and 65 points in 22 playoff games.

“That might be one of the top two or three junior hockey lines of all time,” Hunter says. “They were unbelievable offensively, and they had a good defense. They had guys who could play, as did we. It was a great series.”

The Hawks were nearly unbeatable at home — 30-3-3 during the regular season, matching the mark Portland had on its way to a Memorial Cup crown in 1997-98. The franchise’s all-time best home mark was 32-3-1 in 1985-86.

“Teams would come in, and it was game over after the first period,” Dobson says. “We put them away early.

“In all the years I played and coached hockey, that team was unbelievable with how tight the group of guys were. You always hear that from winning teams, I guess. When you win it’s magical. But we played so hard as a team. We had each other’s back. We believed we were going to win every night.”

► ◄

One Winterhawk was not through with hockey that season. In those years, teams could add one player from other league rosters for the Memorial Cup. Brandon picked up Hunter, who had been voted by teammates as the Hawks’ Most Valuable Player in the playoffs. Brandon lost to Peterborough in the Memorial Cup finals, but he won the MVP trophy there, too.

Hunter wasn’t done with major junior hockey then, either. He signed as an overage player the next season with Regina, which won the WHL title. So Hunter stands as the rare player who participated in a pair of Memorial Cups for different teams.

Though he had a franchise-record 15 straight wins in January and February of ’79, Hunter says he wasn’t as sharp in 1978-79 as he was the previous season.

“I did not have a great year,” he says. “I played way better my first year. I was so worried about making the pretty saves in my draft year. At some point, I just went, ‘Screw it, I’m just going to play hockey.’ And I played really well in the playoffs and in the Memorial Cup.”

Hunter didn’t get chosen in the NHL draft. After three minor-league seasons, his hockey career was over at 23. He makes no excuses about why it didn’t last longer.

“I wasn’t consistent,” he says. “I played in an era with some great goaltenders. A big difference was, they were more consistent than I was. We could all stop the puck. It’s a matter of what you do after a bad goal, and how often do you stop the puck? I had lots of coaches say, ‘Give me one game, I’ll take Hunter in the net. But give me 72, I’m not sure you want him in all 72.’ ”

► ◄

Eighteen players who were regulars on the first three Winterhawk teams played at least one game in the NHL. That’s not including Yakiwchuk, who played four seasons in the World Hockey Association. Eight of them played at least eight NHL seasons — Dave Babych (20), Brown (16), Playfair 12, Peterson (11), Turnbull (11), Currie (nine), Wayne Babych (nine) and Wesley (eight).

All of the former Hawks finished their playing careers decades ago. A look at what they did following their playing careers, and what they are doing now:

The Babych brothers are now 67 (Wayne) and 64 (Dave). Wayne lives in Winnipeg with his wife, Louise; they have an 18-year-old son. Dave lives in North Vancouver, B.C., with his wife Diana. They have five sons and one grandson. Wayne and Dave spent much time after their playing days building and designing golf courses in the Winnipeg area. Dave served as a coach/player development for the NHL Vancouver Canucks for five years and is now an ambassador for the club. In 2025, Wayne was inducted into the St. Louis Blues Hall of Fame.

Keith Brown, 65, and wife Debbie live in Cumming, Ga. They had four children and have eight grandchildren. The two youngest children were afflicted with Leigh’s Disease, a neurological disorder. One of them died; the other is in hospice. The Browns’ devout Christian beliefs have helped get them through it.

After his playing days ended, Keith went back to college and earned his bachelor’s degree in computer engineering. He got a job in software engineering, “and I work in the data world today,” he says. “Still full-time, but not for too much longer.”

Keith Brown (back row, second man from left) and family now live in Cumming, Ga. (courtesy Keith Brown)

Tony Currie, 68, played nine NHL seasons and another three in Europe. He and wife Mary Margaret live on the Georgian Bay north of Toronto in Ontario. He has two sons and seven grandchildren, with one on the way. Tony worked in technology sales for 30 years after his playing days ended.

Jim Dobson, 65, lives in Portland. He has twin daughters, Janelle and Rochelle, three grandsons and a granddaughter on the way. His final season with the Hawks was 1979-80, when he was second in the WHL in goals scored (66) and fifth in scoring (134 points).

“Dobber” was drafted in the fifth round, 90th pick overall, by Minnesota, which had reached the Stanley Cup finals that year. He played parts of five NHL seasons — but only 12 games total — with three clubs.

“I never was given a chance to cut my own throat,” he says. “Give me 10 games with a regular shift. Maybe throw me on the second power play, and let’s see if I can play or not. I never got that opportunity to prove what I could do.”

Dobson played pro hockey for eight years, mostly in the CHL and AHL, retiring in 1986 at age 26. He coached one season with the WHL Seattle Thunderbirds, going 25-45-2. (He was replaced, notably, by Barry Melrose). Dobson moved back to Portland in 1990 and has sold real estate in the area since.

Jim Dobson, who lives in Portland, was a clutch goal-scorer for the Hawks during the 1979 playoffs (courtesy Jim Dobson)

Bart Hunter, 66, worked as a financial advisor for 30 years after his playing days ended. He and his wife of 29 years, Cindy, live in Edmonton and have one daughter and two grandkids.

Ex-Hawk goaltender and his wife of 38 years, Cindy (courtesy Bart Hunter)

Doug Lecuyer, 67, lives in Edmonton. His wife of 42 years died in 2021. He has two children. He played four NHL seasons and was done at 23. “Bubba” (the nickname, given to him by former teammate and one-time Winterhawk Harold Snepsts, comes from Baba Looey, sidekick to cartoon hero Quick Draw McGraw) turned to golf as a second career.

Lecuyer became a member of the Canadian PGA in 1982 and had stints playing on the Canadian, Australian and New Zealand tours. He also participated in the PGA Tour qualifying school one year. He has spent 44 years in the golf business, much of it as a club pro. Lecuyer recently was given a lifetime achievement award by the Alberta Golf Hall of Fame.

Hawks winger Doug Lecuyer later became a golf pro. Here he is with son Jake while being presented a lifetime achievement award by the Alberta PGA (courtesy Doug Lecuyer)

Paul Mulvey, 67, lives in Washington D.C. with his wife of 43 years, Kerri. They have one daughter and two grandkids. “Old Yeller” played four NHL seasons and was out of the league at age 23, in part because coaches wanted him to fight as part of his game.

“It ended my career, because I wasn’t going to be a part of that kind of stuff,” he says.

For about 20 years after his retirement from hockey, Mulvey operated an ice rink in the D.C., area, providing hockey instruction and clinics for youths. He is now director of operations for a facility management business in the area. He is coaching his eight-year-old grandson’s mite travel team. “I’m more excited about that than I was when I was playing,” he says.

Mulvey’s greatest accomplishment during his time in Portland?

“I introduced Brent Peterson to his wife, Tami,” Mulvey says. “Tami and I went to Sunset High together. She was a great friend, and when I learned she was Mormon, I told her, ‘You’re in luck. I’ve got the guy for you.’ ”

Brent Peterson, 67, lives in Nashville with Tami, his wife of 46 years. They have three children and four grandchildren. Peterson had a distinguished coaching career after his playing days ended in 1989. After a two-year stint as an assistant with the Hartford Whalers, he returned to Portland and served seven years coaching the Winterhawks, taking them to a Memorial Cup championship his final season.

Following that season, Peterson became associate head coach of the expansion Nashville Predators. He stayed on the Predators’ coaching staff until his retirement in 2011, nine years after his diagnosis for Parkinson’s Disease. He has raised more than $2 million to aid those living in Tennessee with the disease through the Peterson Foundation for Parkinson’s, which was established in 2003.

Larry Playfair, 67, lives in Buffalo, N.Y., with wife Jayne. They have four children, 10 grandkids and one on the way. Following his retirement as a player, he began a second career in commercial real estate. “That’s what keeps me busy,” he says.

Playfair was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease in 2020. “If you didn’t know I had it, you might not know I have it,” he says. “I have way more good days than bad days.”

Perry Turnbull, 66, lives in St. Louis with his wife of 42 years, Nancy. They have two children — their son Travis, 39, is playing pro hockey in Germany — and five grandkids.

After his playing days ended, Turnbull ran a travel agency, sold the business, played and coached for a pro roller hockey team, coached ice hockey and, for the last 32 years, has operated the Midwest Sport Hockey facility in suburban St. Louis.

Turnbull had some serious health issues in 2024. He developed peritonitis — fluid around the heart caused by a bacterial infection — and was in an emergency room four times. “They started me on Prednisone,” he says. “It took me months to get off it. But I’m feeling much better now.”

Perry’s body parts have taken a beating.

“I have had two shoulder surgeries, four knee surgeries, two ankle replacements,” he says. “I wouldn’t change it for the world. What goes around, comes around, but some days I think, ‘There’s no way I inflicted this much pain on other people.’ ”

Ken Hodge, 79, is retired and lives in Tualatin. He has been in a relationship with Carol Lee Robinson for 23 years. Hodge has three children, five grandkids and another on the way. He is a member of Columbia-Edgewater Country Club in Portland and is a seven-handicap. Hodge plays golf “almost every day in the summer,” and three to four days a week throughout the rest of the year.

Coach Ken Hodge and significant other Carol Lee Robinson. Carol is holding Myah; Ken is holding Millie. (courtesy Ken Hodge)

Finally … my top 10 players from the Winterhawks’ first three teams:

10. Tony Currie. His goal-scoring and shot-making the first season is somehow overlooked.

9. David Babych. Manchild who would have been higher on the list had we included the 1979-80 season.

8. Larry Playfair. The Hawks’ policeman the first two seasons, and a rock-solid defenseman.

7. Paul Mulvey. Big, tough winger who had consecutive 43-goal seasons.

6. Mike Toal. Played only the third season, but was the second-best center in the league.

5. Bart Hunter. One of the best goaltenders in the league the last two seasons.

4. Wayne Babych. Speed and strength carried him to back-to-back 50-goal seasons.

3. Brent Peterson. Tremendous all-around player and Portland’s leader the first two seasons.

2. Keith Brown. I’d put him up against any defenseman in Winterhawk history.

1. Perry Turnbull. The only one who played key roles all three seasons, finishing with the best season of them all.

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.