The first Winterhawks: They brawled, they won, they had a lot of fun

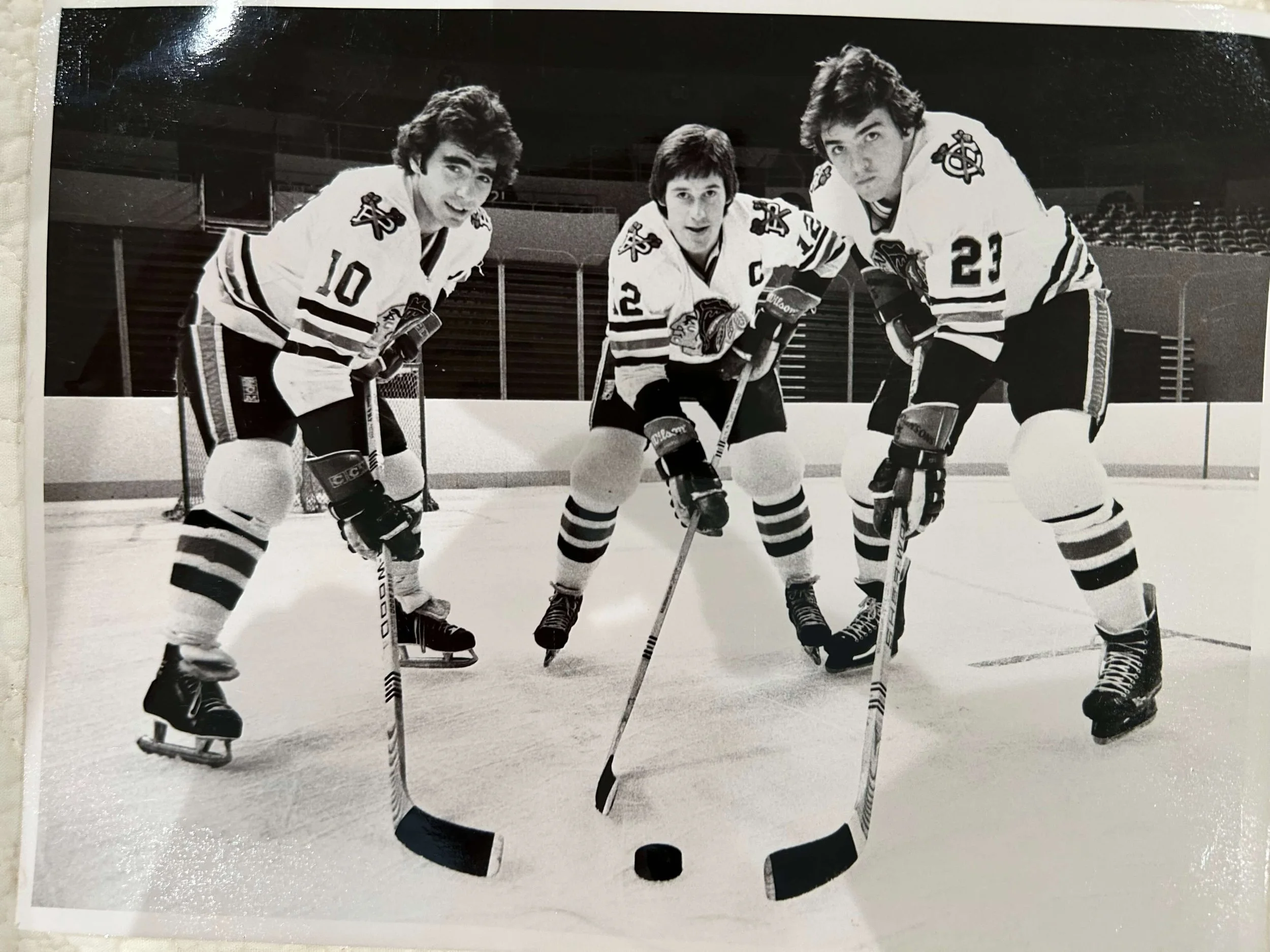

From left, Wayne Babych, Brent Peterson and Paul Mulvey formed the No. 1 line on the first Winterhawks team in 1976-77 (courtesy Tami Peterson)

Updated 1/13/2026 9:50 AM, 1/17/2026 11:16 AM

(The Portland Winterhawks are celebrating their 50th Western Hockey League season. This is first of a two-part series detailing the Hawks’ first three seasons.)

It began with a bit of a whimper on Sept. 26, 1976. The Victoria Cougars beat the Winter Hawks 4-3 at Victoria Memorial Arena in the first-ever game for the fledgling Portland team in the Western Canada Hockey League.

Two weeks and seven road games later the Winterhawks (they didn’t become the “Winterhawks” until 2009, but we will use their moniker that way in this article), won their home opener over New Westminster 7-5 before a Memorial Coliseum crowd of 4,078.

A new era of Portland hockey had begun.

This season is the Winterhawks’ 50th in Portland after a move from Edmonton for the 1976-77 campaign. The club is in the midst of a season-long celebration, paying monthly homage to groups of their top 50 players of all time.

“I just can’t believe that 50 years have gone by,” says Larry Playfair, a fixture on defense on the Winter Hawks’ first two teams. “Where has the time gone?”

I covered the first three Winterhawks seasons for the Oregon Journal, then Portland’s afternoon newspaper owned by The Oregonian Publishing Company. I was 23 and had been working at The Journal for little more than a year when sports editor George Pasero called me over to his desk.

“Kerry, we are getting a junior hockey team in town, called the Winter Hawks,” he told me. “And you are going to cover them.”

I didn’t know what to say. Junior hockey? Little kids skating around on the ice? This is going to be my beat?

“But George, I have never even seen a hockey game,” I sputtered.

He smiled and took a puff on his cigar.

“That’s OK,” he said. “You’ll learn.”

Thank God for the late Ron Olson, who had covered the Buckaroos and was on the Winter Hawks beat for The Oregonian. We sat next to each other in the press box and, though we were competitors, he generously helped me understand the basic rules the first few games. After a month or so, I had gotten with the flow. I found that I liked the game, fast, physical — at times in that era, vicious — and exciting.

And I liked the Hawks players, who were only a little younger than me — from 16 to 19. I got along well with their owner/general manager, Brian Shaw, and coach Ken Hodge. I covered them through three seasons, ending with a splendid run to the league championship series in 1979. They lost in six games to the Brandon Wheat Kings to fall just short of their goal to advance to the Memorial Cup, junior hockey’s equivalent to the NHL’s Stanley Cup.

After that, I was off to other assignments for The Journal. Through 45 years writing sports for Portland newspapers, I had only one more season on the Hawks beat — with The Oregonian in 1997-98, when they won the coveted Memorial Cup in a tournament staged in Spokane.

In honor of the franchise’s 50-year celebration, I decided to write a piece on those first three Winterhawks teams. I identified a dozen players off those teams I wanted to interview, most who went on to successful NHL careers.

Over the past few weeks, I have reached 11 of them, missing only on defenseman Blake Wesley, who is said to be living in Austria. Two key players on those first teams are deceased. Dave Hoyda died in a house fire at age 57 in 2015. Dale Yakiwchuk passed away from cancer at 64 in 2024. I also interviewed Hodge, chief scout Wayne Meier and trainer Innes Mackie. (Shaw died at age 62 in 1993.)

I have kept in touch with Brent Peterson, the captain of the first two Portland teams and later coach of the ’98 Memorial Cup champions. I did a story with Dave Babych for The Oregonian in the late ‘90s, near the end of his splendid 20-year NHL career. I see Jim Dobson, who lives in Portland, around town from time to time. Other than that, I hadn’t spoken with any of the original players in, well, nearly a half-century.

I was surprised that most of them said they remembered me. “Do you still have long hair?” one of them asked. (No, regrettably, not entirely by choice.)

Following are the results of a formidable time capsule project, bringing Winterhawk fans back to the franchise beginnings. Even if you are not a hockey fan, I hope you find it interesting.

The Edmonton Oil Kings were a founding member of the Western Canada Hockey League. They were a major junior league club owned, operated and coached by Bill Hunter, one of the league’s co-founders and also helped launch the World Hockey Association. (The WCHL became the Western Hockey League in 1978). Hunter’s son, Bart, turned out to be an important figure in Hawk heritage. More on that later.

The Oil Kings were a junior-league dynasty in the 1960s, reaching seven straight Memorial Cups from 1960-66. Bill Hunter was also an owner of the Edmonton Oilers, who joined the WHA — a competitor to the NHL — in 1971, and things began to go downhill for the Oil Kings.

“We shared the hockey scene in Edmonton with the Oilers and weren’t drawing well,” says Hodge, who coached the Oil Kings for 2 1/2 seasons, including the first half of the 1975-76 campaign.

Shaw was a former major junior coach and was also head coach of the Oilers from 1973-75, compiling a record of 68-63-6. Ownership relieved Hodge of his coaching duties with the Oil Kings midway through the 1975-76 season, and shortly thereafter Shaw — with Hodge and a few others as minority owners — purchased the club. “I had a small percentage, and that grew as time went on,” Hodge says.

“We spent the second half of the season playing in Edmonton before moving to Portland,” says Hodge, whose legacy with the Hawks may never be matched. He served as head coach from 1976-93, also working as general manager the last two seasons. He continued as GM and president through 2008 and worked as a consultant from 2008-15 before retiring at age 69.

Today, Hodge stands second on the regular-season wins list for WHL coaches with 742, behind only Don Hay with 752. Hay, ironically, served as an assistant coach with the Winterhawks under Mike Johnston for three seasons (2018-21).

When Hodge retired from coaching, he had the most WHL playoff victories with 101. During his 32 years as head coach and GM, the Hawks made the playoffs 26 times and won two WHL and Memorial Cup titles. Nearly 100 of the players Hodge coached reached the NHL. Eleven of those played in the Hawks’ very first season — 12 if you include Keith Brown, who played two games as a 16-year-old that season.

Hodge wasn’t a red-ass as a coach, but he was old-school, as were New Westminster’s Ernie “Punch” McLean, Victoria’s Paddy Ginnell and many of the junior hockey coaches of the era.

“Hodgie was a hard coach,” says Wayne Meier, Portland’s first scout. “He is a dear friend and was one of the best coaches in the league — very well-respected. Some of the other coaches were a little more personable off the ice. Ken never smiled. I knew there was another side to Ken, because he would golf with his buddies and laugh and have a great time.”

To a man, though, the players I interviewed for this article enjoyed playing for Hodge.

“Ken was an exceptional coach,” says Tony Currie, the leading scorer on the first Winterhawks team. “I was a bit of a brat, living away from home for the first time. I wasn’t the easiest guy to handle. Ken was good to me. I have nothing but good things to say about him. He knew the game, knew his players and put guys in position to succeed.”

“Hodgie was no-nonsense,” David Babych says. “You knew where you stood. He had us working like a machine.”

“He was pretty much a silent guy,” Paul Mulvey says. “He wasn’t the coach I grew up being, talking to players, discussing things and being emotional and happy and sad. Ken held that to himself. But he was effective in his own way.”

“He got mad when he had to, but he was even-keeled most of the time,” Wayne Babych says. “He was great to play for.”

“Hodgie did so much for the team,” Brent Peterson says. “He was always there for you. He was a man of very few words. He didn’t say much, but when you heard him holler on the bench — ‘Peee-terr-sunnn!’ — you knew you were doing something wrong.”

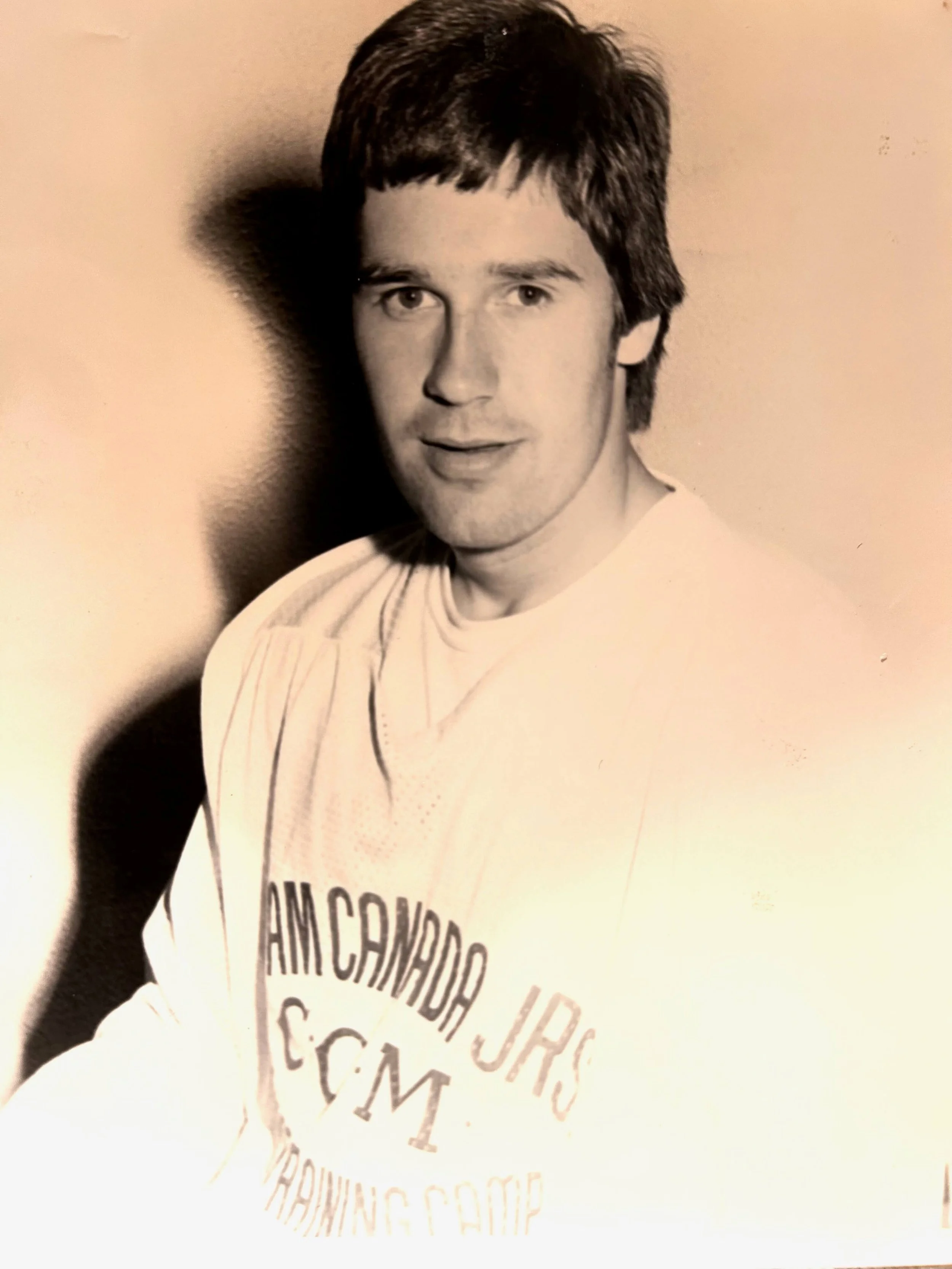

Brent Peterson, captain of the first two Winterhawks teams, later coached the team to the 1998 Memorial Cup title (courtesy Tami Peterson)

“Hodgie was quiet until he barbecued you,” Larry Playfair says with a laugh. “He did that a couple of times to me, but it was OK. He also coached. He didn’t just yell and scream and not give you direction. He would let you know what he wanted done. That was the first real coaching I had gotten. Ken Hodge absolutely helped prepare me for the next level.”

“A wonderful coach,” Keith Brown says. “He did everything. He had no assistants. No video help. He was good behind the bench, handling the players, caring for his players. I had a lot of coaches in the NHL, and he would be right up there as my favorite coach.”

Portland’s best player through the first three years was Perry Turnbull, a physical winger who scored 75 goals and was MVP of the league in 1978-79, his third year with the club. Turnbull notes that Hodge was 30 when he came to Portland in 1976.

“Hodgie needs a pat on the back in this story you are writing,” Turnbull says. “He came in as a young coach. You have no polish when you start. You are learning by yourself. I don’t think he had any mentors. Back then, it was just, ‘Use your best players and tell them to go out and play.’

“But he got a lot better from Year 1 to Year 3 — a lot better. His level of coaching went so far up through my time there. He learned and got better each year. By my last year, he was a really good coach.”

► ◄

The Oil Kings went 25-42-5 and finished fifth in the six-team West Division in 1975-76.

Shaw and Hodge then moved the club to Portland. Why Portland?

“That was Brian’s decision,” Hodge says. “I went along with it, but at that time I thought Spokane would be a better option.”

Hodge’s thinking was twofold, One, the Winterhawks were to arrive in Portland only two years after the demise of the Buckaroos, a staple of the professional minor-league Western Hockey League. The Buckaroos had opened 10,000-seat Memorial Coliseum in 1960 and won three WHL championships over the next 11 years, developing a strong following. But the league collapsed after the 1974 season, leaving a void in Portland for hockey.

“It was not an easy thing after the success the Buckaroos had just in front of us,” Hodge says. “Plus, Spokane had a 5,000-seat building, a great size for junior hockey at that time. And it was a little more convenient for travel at that time.”

Indeed, Portland was the first U.S. city in what was a 12-team WCHL in 1976-77. (Seattle came along the next season, Billings, Mont., joined up in 1978-79, Great Falls came in 1979-80 and Spokane was added in 1980-81. Neither Billings nor Great Falls lasted long, though.).

That first season, the shortest road trip was to New Westminster, B.C., a five-hour drive. A bus trip through the western Canadian prairies to Saskatoon, Regina, Brandon and Flin Flon was a days-long marathon. Spokane, at least, was five hours closer.

(Today, there are 23 teams in the WHL, including six in what is now called the U.S. Division.)

“The people in Spokane had a senior league team, and they weren’t all that interested,” Meier says. “They suggested to Brian that Portland could be an option. The Buckaroos had folded. The facility was available.”

So Portland it was. Shaw saw potential to win over the fan base. He brought along Innes Mackie, a former defenseman for the Oil Kings who had served the last season in Edmonton as the team’s trainer. Mackie, then 21, had played for both Shaw and Hodge in Edmonton. He drove with Shaw to Portland in the spring of 1976 to talk with city officials and scope out the Coliseum.

“I couldn’t believe how green everything was,” says Mackie, 71, now living in Kennewick, Wash. He retired in 2020 after 43 years as a WHL trainer — 32 with Portland and the final 11 with Tri-City.

Meier had served as a scout for the Oil Kings. Shaw hired him as a full-time scout for the Winter Hawks. In those years, each WCHL club had territorial rights to players. Portland’s territory was Edmonton.

“We had exclusive rights to (Edmonton players) until they were 16,” says Meier, 81, who lives in Canby and retired in 2018 after a 45-year scouting career, including 31 in the NHL. “That became a real advantage for us. I was firmly entrenched in the Edmonton hockey program. I knew all the players.”

He has three Stanley Cup rings from his time working for the Pittsburgh Penguins — 2009, ’16 and 17.

“Blows my mind,” Meier says. “That with a kid who never played hockey growing up.”

Meier grew up a fan of the Edmonton Flyers of the old WHL, along with the Portland Buckaroos.

“My mother couldn’t figure out why I had to go to every game, but I was mesmerized,” Meier says. “I knew the players on the Buckaroos and Seattle Totems as well as the Flyers. I wasn’t just watching my team; I was watching good players throughout the league.”

Meier was the first full-time scout in the WCHL. He was also the only scout the Hawks used for several years. (Today, every WHL team employs a staff of several scouts. Portland has one full-time scout, Matt Davidson, who lives in Edmonton. The Hawks also employ 15 part-time scouts who cover territories throughout western Canada and the U.S.)

“Wayne did an excellent job, and played a major role in the recruiting of players for us,” Hodge says.

The first few seasons, Meier would work in the office in October, then leave for Edmonton and not return to Portland until May. Each team had a territorial “player list,” which started at 90 spots during training camp and eventually was cut to 70. This was in the days before a draft was installed.

“You were continually adding and subtracting players from your list,” Meier says. “If they didn’t sign, they didn’t play, or played Tier II. Each team had its own territory. The league gave us Edmonton. We had exclusive rights to players until they were 16. That became a real advantage. I was firmly entrenched in Edmonton hockey. I knew all the players. It was a major development area.”

Meier listed and signed many boys from the area the first few years of the Hawks’ existence, including Brent Peterson, Keith Brown and Wayne and Dave Babych. There was also an annual eight-team tournament in Swift Current, Sask., featuring list-eligible 16-year-olds.

“All the best players in western Canada were there,” Meier says. “First team that lists them, gets them. The other scouts saw the same players, but they had to report to their GMs. As they were reporting, I was listing (players) with the league office. Brian didn’t know who to (list). He gave me full autonomy. Brian, Ken and I worked extremely well together.”

There was a fourth component to the front office — Jann Boss, who served as business manager from the very first season to a time near to her death in 2007.

“Jann was as valuable to the franchise as anybody,” Meier says. “The four of us ran that hockey team. The kids called her ‘Mother Hawk.’ She kept Brian in check a bit. She was a very important piece of the organization.”

Meier scouted for Portland from 1976-83, then was hired as a West Coast scout for the NHL Detroit Red Wings. After three years, Shaw lured him back to Portland by doubling his salary and giving him the title of director of player personnel.

“But when I came back (in 1986), the honeymoon was over,” Meier says. “I stayed another four years, then went back to Detroit.”

Meier scouted for the Red Wings, Panthers, Ducks and, for the last 12 years, with the Penguins.

“I worked with really good people in the NHL, and I got the Stanley Cup rings,” Meier says. “But I got more self-satisfaction from my years with the Winterhawks than I had during my entire NHL career. I really enjoyed my time with Portland.”

► ◄

Shaw was what I would call a “piece of work.” He loved attention and did a grand job getting it. He liked the media and once left a gift — a bottle of hooch — on my hotel bed on a road trip. Brian was quotable and great to work with. At times, he would lambast officials and opposing coaches and, occasionally, his own players. But he generally treated them well and got good results.

“I liked Brian,” David Babych says. “Everyone has their opinions on him, but he and Ken treated us so well. If you needed anything and were scrambling a bit, Brian would help you out. Both of them treated us like men. If you did something stupid, they would call you on it. They had a valuable franchise they didn’t want to disrupt in any way.”

As personalities, “we were quite different,” Hodge says. Hodge was soft-spoken and introverted. Shaw was bombastic, at least professionally.

“Hodgie was pretty quiet,” Hunter says. “He’d tap his stick and didn’t say a lot. Brian often had a lot to say.”

The duo, however, seemed to mesh well together.

“Brian was creative for his time,” Hodge says. “He was demanding. He worked hard. He enjoyed the game and had good relationships with the other owners and GMs throughout the league as well as the league office.”

In my interviews with players nearly a half-century later, many of them used the word “flamboyant” to describe him.

“Brian was quite the dresser,” Wayne Babych says. “He never wore a suit more than once a year.”

Shaw was like a carnival barker as he worked to promote his product in a new city.

“He knew how to sell,” Wayne says.

“He liked to dress, and had the suits and all that,” says Brown, a great defenseman with the Hawks from 1976-79. “But he really cared for his players. They had to make it financially and get people in the building and put a good product out there and market it. He did a fantastic job. I thought the world of Brian, Ken and Innes. They were a special group of people.”

“Brian was wonderful,” Wayne Babych says. “I never had one problem with him. He treated us like gold. We always stayed at the best hotels. For a guy who had very little education and was self-taught, it was amazing he had the success he had in hockey.”

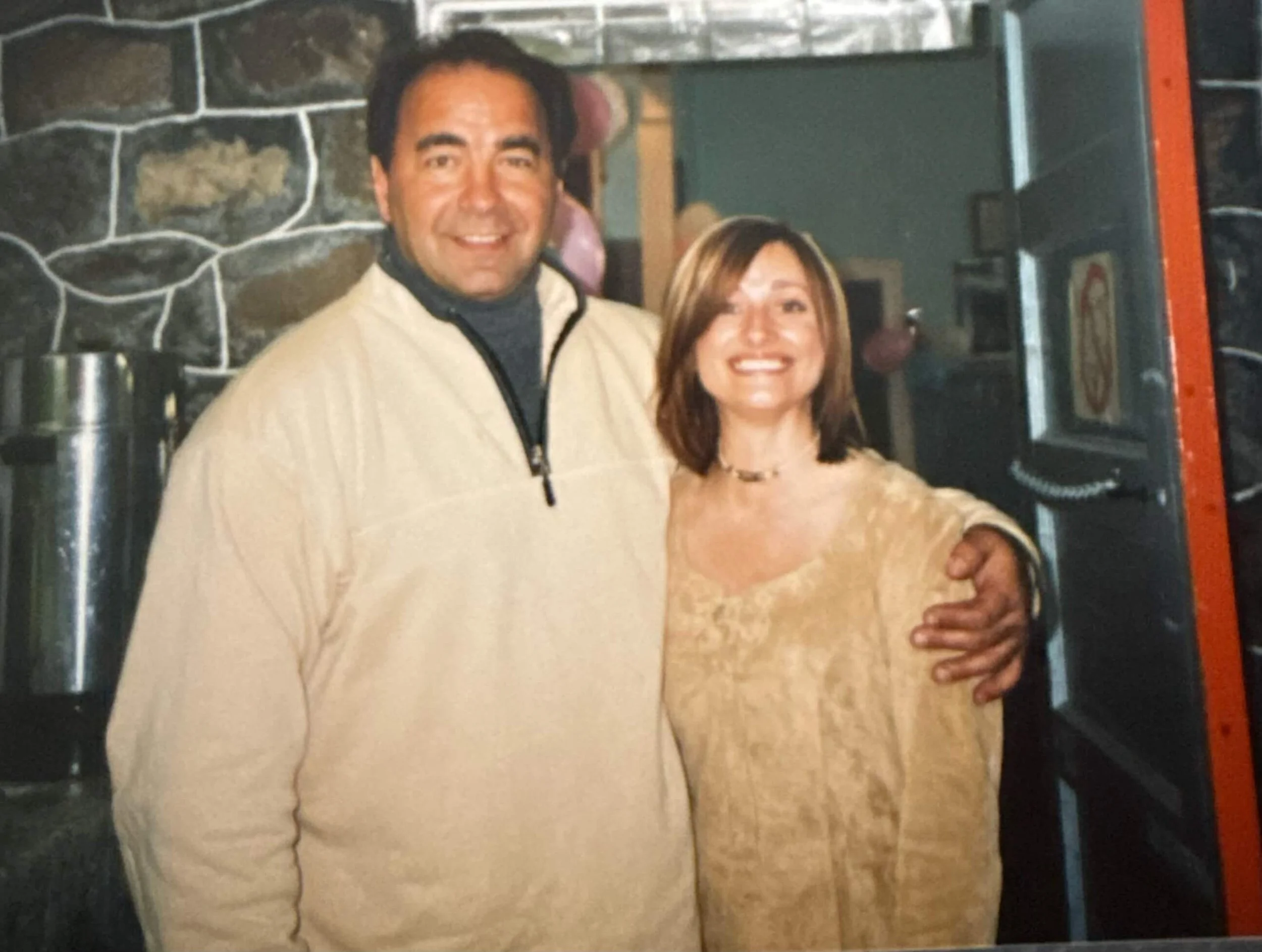

Wayne Babych today with and his wife Louise (courtesy Wayne Babych)

“Brian was dynamic,” Mulvey says. “He was the kind of guy who would try to motivate you and get you to the next level, one way or the other.”

Not everyone loved Shaw.

“He was flashy and intimidated us,” Playfair says. “We gave it back to him sometimes, though. The guys busted his chops, and that was fun.”

The team’s nickname for Shaw was “Snuffy.” Not to his face, of course.

“Hodgie ran the dressing room, but Brian liked to come in and say his piece,” Hunter says. “I know I listened to Ken more than Brian.”

“I didn’t get along with Brian like some people did,” Peterson says. “I had a hard time with him. He had a fiery disposition and would go crazy some nights. A big personality. But he was generally good to the players, and was a great marketer of the game.”

► ◄

In the summer of ’76, Shaw and Hodge flew to Portland from Edmonton for a promotional tour and brought with them players Mulvey, Peterson, Wayne Babych and Dave Hoyda.

“We had no idea where Portland was, or what to expect,” says Mulvey, a native of tiny Merritt, B.C., and a 6-4, 215-pound winger who had played the previous two seasons with the Oil Kings. “They put us up at the Thunderbird Hotel across the street (from Memorial Coliseum). We got treated like celebrities. We hadn’t got that treatment in Edmonton. We were like, ‘This is going to be phenomenal.’ ”

Nearly a half-century later, from his home in Washington D.C., Mulvey speaks with reverence about his time in Portland and with the Winterhawks.

“Such wonderful memories of my teammates and of Portland in general,” says Mulvey, 67, who played four NHL seasons. “I have good memories of my NHL days, too, but they are not the same as my time in juniors, when you are young and still developing. The Portland days were exciting. The bus rides were long and hard, but also times when you bonded with teammates and made great memories. Fabulous memories.”

Many of the Winterhawks had played together with the Oil Kings. Not Playfair, who had no WCHL experience. A native of Fort St. James, B.C. — population 2,200 — he had played the previous season for Tier II Langley in the Kamloops organization and was traded to what would become the Winterhawks after the season.

“I was apprehensive about my chances to make the team,” Playfair says. “I didn’t know one player on the team. When I got to Portland, it was all Greek to me. It was just such a new experience. But it didn’t take long for me to feel comfortable. I loved the arena. It was fun playing there. Good weather — no snow — and it didn’t take long for the fans to embrace us.”

The Babych brothers lived three miles from the Edmonton Gardens arena and Northlands Coliseum, which replaced it in 1974.

“The biggest thing was having to leave your parents,” Wayne Babych says. “It was tough being away for about the first month we were in Portland. But it turned out to be the favorite place I have ever lived.

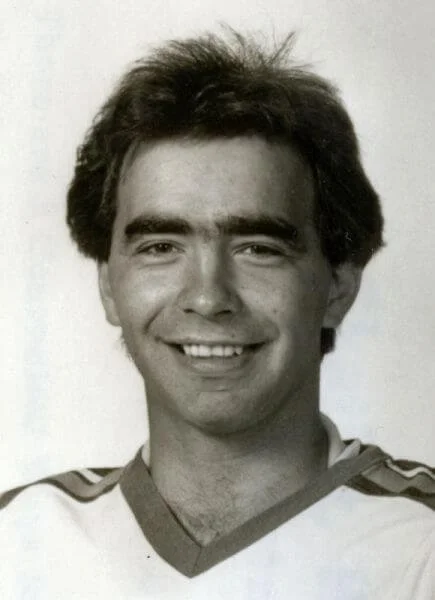

Wayne Babych had back-to-back 50-goal seasons for the Winterhawks in the first two years of the franchise

“A lot of that had to do with Brian and Ken and how they treated us, which was second to none. The weather was great. The people we met were fantastic. And I liked the building. The boards would move a little bit, and any time there there was a big hit, the crowd went crazy.”

The Hawks didn’t attract large crowds, though, until the second half of the third season. Average home attendance for the inaugural campaign was 3,457, about one-third of the arena’s 10,000-seat capacity.

“It was a bit of a struggle,” Mackie says. “There were the Buckaroo fans, but a lot of those people were too old or had passed away. We couldn’t shake that ‘junior hockey’ image. People thought our players were 10 to 12 years old.

“We didn’t get favorable press from some of the TV commentators, either. Doug LaMear had covered the Buckaroos for years, and they were no saints. I remember one telecast he said, ‘There was a big brawl at the Coliseum tonight. I’m not even going to mention the score.’ ”

There were several brawls in the first three seasons. It was the era of the “Broad Street Bullies,” the Philadelphia Flyers, who used aggressive, physical and often brawling play to claim back-to-back Stanley Cup titles in 1974 and ’75.

“The Flyers played dirty hockey and got away with it,” Peterson says. “Everybody in the hockey world said, ‘If you want to win, you gotta play like that.’ ”

New Westminster was the gold standard in the WCHL in those days, and they played the Flyers’ style of hockey.

“That was successful for New Westminster,” Turnbull says. “You see success, and you emulate that.”

Shaw and Hodge built their team along those lines — big and tough. On the first Portland team, Mulvey and defenseman Playfair were both 6-4 and 215. Winger Dale Yakiwchuk was 6-4 and 205. Hoyda, a winger who became a noted fighter in the NHL, was 6-1 and 200. Defensemen Blake “Big Red” Wesley and Jeff “Chief” Bandura were both 6-1 and 200. Turnbull was 6-2 and the toughest 205 pounds in the league. Wayne Babych was 5-11 and 190 and could throw with the best of them.

“We may have had the biggest team in junior hockey,” Babych says. “Dougie Lecuyer (a 5-9, 190-pound winger) and myself were the smallest guys. Dougie was a skilled hockey player and was crazy at the same time. When he lost it, he would skate to our bench with his stick over his head in two hands, and the whole bench spread. You’ve never seen a bench move so fast to get away from the stick. And it terrified the other team. It was nuts.”

“The game was quite different then,” Hodge says. “The coaches at that time — like Paddy Ginnell in Victoria and Ernie McLean in New West — were very aggressive-minded. They believed in tough hockey. To play with them, you had to respond.”

Few were as tough as Turnbull, who probably fought as much as any Hawk, at least through his first two seasons.

“I was supposed to be a goal-scorer,” Turnbull says. “They talked me into doing that stuff.”

He laughs heartily. “I’m just kidding. We had a lot of guys who could go. ‘Hoyds’ was so tough. Larry was the toughest guy we had. ‘Hoyds’ was close. I don’t know that I liked to fight, but I had a whole bunch of Babych in me.”

The Hawks weren’t above using intimidating tactics against their opponents. During warmups of some games, they would shoot pucks down to the opponents’ end just for fun.

“Perry would skate down and gather all the pucks; so the (opponent) wouldn’t have any pucks to warm up with,” Peterson says. “Hodgie would come in the room before the game when we were getting dressed when we were getting ready to go back onto the ice after warmups. He would go, ‘OK, Hoyda, you and Yakiwchuk take a penalty here, and Babych and Peterson, you guys clean up the mess and kill the penalty.’ He was calling out the penalty guys before they took the penalties. First shift, Hoyda would punch somebody in the head and Babs and I had to clean it up.”

Eight Hawks accumulated 100 or more regular-season penalty minutes that season, and four — Mulvey, Turnbull, Hoyda and Bandura — were over 200. Playfair had 199. Portland totaled 2,357 as a team. (By way of comparison, Seattle led the WHL with 1,005 penalty minutes last season. Nate Corbet, who played with both Medicine Hat and Kelowna, was the individual leader with 176 minutes. Medicine Hat’s Oasis Wiesblatt was second with 148.)

Portland wasn’t a goon squad, though. The roster was young but plentiful in talent. There were six 20-goal scorers, led by 5-11, 175-pound winger Tony Currie, who was third in the league with 73 goals and fifth in scoring. The defense was sturdy with veterans Bandura, Eric Christianson and Jim Cross and future NHL players Playfair and Wesley. Goalie Randy Ireland would get a cup of coffee in the NHL at age 21.

“That was a fun team to coach,” Hodge says. “They were big and aggressive and had a good attitude.”

“We were a monster big team,” Mulvey says. “Most teams didn’t want to challenge us because of Larry and Yak and Hoyda and me and Perry and Blake. All of us were really good fighters. But we also had a good blend of talent.”

The No. 1 line featured Mulvey and Babych centered by Peterson, the team captain. They had played on the same line the previous two seasons in Edmonton. Mulvey would score 43 goals, Babych 50 that season. Peterson had 34 goals and a team-high 78 assists.

“Brent was a calming influence, an influencer with teammates who were a little bit over the top,” Hodge says. “He played an overall game, ran our power play, killed a lot of penalties.

“Wayne was a very good player, but he was fortunate he had a center iceman like Brent through his whole career here. Brent kept him on the straight and narrow and headed in the right direction.”

“Brent was a left-handed shot,” Babych recalls. “He always passed to me first, because I was on his forehand. In the face-off draws, he was pulling it back to me. I scored a lot of goals off the draw. He was a very smart hockey player. With Paul, the perfect big left winger for that era, we complemented each other very well.”

“Brent was a talented, unselfish center man who made both Wayne and me look better than we were,” Mulvey says. “ ‘Normie’ was a good Mormon. Never swore, never got high, never got low. An all-star quality human being. Babs was a happy guy who was so talented, so fast and strong and had such a great shot. It was easy to play with those two.”

“Babs loved to score — he didn’t want to share the puck with us,” Peterson says with a laugh. “What a great shot he had coming down the wing. That’s how he beat everybody. He waited for Mulvey and I get the puck to him in the slot so he could score.”

Meier says in his time with the Hawks, “Brent and Richard Kromm were our two best captains ever. Brent was the best player ever during my reign.”

Currie played against Babych in Tier II and watched his development.

“Babs was a powerful guy — strong as an ox, with long arms,” says Currie, who also played four seasons with Babych with the St. Louis Blues. “He could really handle himself. He learned how good a fighter he was. His confidence went up from there. He had a massive slap shot and he made his own room on the ice, because he was a tough guy.”

Peterson had been a standout football quarterback and basketball player in Calgary before joining the Oil Kings as a 15-year-old. He was a great athlete, but deportment was what set him apart.

“Brent was a class act,” Currie says. “There was a reason he was the captain. He had that kind of character. He played a solid 200-foot game — a very intelligent, all-around good player.”

“Pete was magnificent,” Turnbull says. “Not just as a leader, but as a human being.”

Currie says the move from Edmonton to Portland “was the best thing that ever happened to me. I really enjoyed the town. To a person, from the billets to the fans, it was an absolute treat. There’s a reason why Portland has continued to have such a successful franchise. It’s a great place to play. It was in Year One, and I am sure it still is now in Year 50.”

Currie had another reason to like Portland. He was a big basketball fan. His season in Portland was the year the Trail Blazers won the NBA Championship in a building they shared with the Hawks.

“What a treat to watch them,” Currie says. “Many times if we got back from a trip at the right time, we would sneak in and watch a bit of their practice. Twardzik, Lucas, Walton, Gross — I was definitely a Trail Blazer fan.”

During the 1976-77 season, Currie played on the second line with Yakiwchuk and Hoyda. Yakiwchuk was a precise passer and puck-handler — he had 53 assists to go with his 24 goals in 59 regular-season games — and was there, along with Hoyda, to take care of any interference Currie might have.

“I scored so many goals because of the guys around me, Yak being a big part of it,” Currie says. “He was an intelligent player. Hoyds made a lot of space for me. I was a shooter. Seventy-three times, somebody put the puck on my tape at the right time. It’s always your linemates. Tip the cap to the guys I played with.”

Currie is being modest here.

“Tony’s moves are as good as any player I have ever coached,” Shaw told me then.

I referred to Currie in print that season as Tony “Hurry” Currie, because he got up the ice so quickly. But the nickname that caught on was “Shotgun Tony.”

“I scored a goal during my rookie year with the Oil Kings, and for whatever reason, I went down to one leg, kicked the other leg and pumped my arm in the air,” says Currie, who did the maneuver after every goal he scored in Portland. “Someone called that ‘The Shotgun Shuffle.’ It stuck. I played with guys in the NHL who had played in (the WCHL) and they still called me ‘Shotgun.’ ”

Turnbull, who would play four NHL seasons with Currie in St. Louis, recalls Currie as “a highly skilled player. He was one of the first guys who could toe-drag the puck. He wasn’t a big guy, but he still played a little bit nasty. That was the culture back then.”

► ◄

Peterson, like most of his teammates, was initially apprehensive about the move from Alberta to Oregon.

“We were all scared,” he says. “The guys were homesick. From September to Christmas that first year, I really had a hard time being away from home.”

It didn’t help that the Hawks began the 1976-77 season with a seven-game road trip — and went 0-7. That remains a club record for most losses to begin a season.

“We had a terrible start,” Peterson recalls.

Also, Lecuyer — who had scored 40 goals for the Oil Kings the previous season, notched a hat trick early against New West and had scored six goals in Portland’s first five games — was traded to Calgary. Lecuyer was initially suspended by the Hawks, then dealt back to his home province. Hodge called him a “bad apple” and spared no words in a story I wrote on reasons for the trade.

“Doug was a very difficult person for a coach to handle,” Hodge said at the time. “He has had a great deal of problem accepting any discipline from our club. Doug is not a bad-living person and is a super hockey player, but he couldn’t deal with certain rules and regulations and was having a detrimental effect on the club. We have put up with him for three years because we have so much respect for his abilities, hoping he would mature and grow out of it, but he hasn’t. Everybody knows he is a problem child, spoiled in many regards.”

Currie, a close friend of Lecuyer’s, said his teammate was homesick.

“When you get right down to it, Doug just didn’t want to play hockey badly enough. He quit on us, really,” Currie told me then. “We’re disappointed. It shocked us.”

Lecuyer went on that season to score 40 goals with 42 assists in just 50 games for Calgary. But things turned out pretty well. In exchange for Lecuyer, the Centennials sent a 17-year-old Turnbull to Portland, which turned out to be one of the great deals in franchise history. And ironically, the Hawks reacquired Lecuyer in the offseason, so had both players with them during the 1977-78 campaign.

Turnbull was a native of Rimbey, Alberta, a tiny berg an hour and a half southwest of Edmonton.

“I didn’t want to be involved in a trade to Portland,” he says today. “I wasn’t happy about getting traded, period. I had no clue what Portland was like. It was hard for me in the beginning. It took me a little while to warm up to it.”

But not that long.

“The weather was a lot milder,” he says. “It was a nice city. I remember going to the Lloyd Center, where they had an ice rink and you could walk around. The people were really nice, and we had a very good hockey club. It was just a great experience.”

Around the time of the trade, Peterson called a players-only meeting.

“OK, so Doug got traded, we aren’t playing well and guys want to be home with Mummy,” Peterson said. “But we have a bunch of good players. Let’s get it together.”

“We were a really good team after that,” he says.

There was plenty of rough stuff ahead, though. In Portland’s second win, 6-2 at home against Victoria — a game in which the Hawks won the shots-on-goal battle 47-22 — there were 10 fights and 165 penalty minutes.

“Victoria did it intentionally,” Hodge told me then. “They realized they couldn’t skate with us. By the middle of the second period, we were up 4-1 and they just gave it up. It’s hard to stay out of fights when somebody else wants to fight.”

Victoria coach Paddy Ginnell told a different story to me: “I blame the officials. They let it get out of hand by the second period. I have never in my life seen such a crude job of officiating. The problem was (the Hawks) running at us — cross-checking, holding, slashing, kicking, jumping our guys. That’s not hockey. It was a f**king football game, for Christ’s sake. We wanted to fight? No way. We’re not a rough hockey club. We’re little. They would kill us.”

I even got a quote from referee John Fitzgerald: “Most of the fights were unnecessary. Two guys would bang on the boards, intimidate each other, drop their gloves and go at it. I haven’t seen anything like that for a long time.”

Two games later, in a 4-4 tie at home against Kamloops, tempers flared again. The glass partition between the teams’ benches got knocked over and suddenly a brawl ensued, spilling into the stands at the Coliseum. Hodge and Kamloops coach Ivan Prediger got into it, and Prediger belted Hodge in the face. The WCHL administered suspensions of 20 games to Prediger and 10 games to Hodge.

“I got the suspension for not controlling my bench,” Hodge says today.

“We knocked the partition down, and then it all started.”

Shaw took over coaching duties as Hodge served the suspension. Toward the end of the his “interim coach” tenure, Portland won an 8-7 thriller at home against Kamloops. Shaw unleashed a torrent about referee Al Paradis to me afterward that could hardly have not caught the attention of the WCHL office.

“Isn’t that Paradis something?” Shaw began. “It’s impossible to promote hockey in a center like Portland when we have an incompetent official come in. He should have been wearing green and orange (the Chiefs’ colors). He is so scared of our hockey team… he did nothing but threaten our players with misconducts all night.

“I’m not saying we didn’t deserve our penalties, but how can he ignore theirs? He let two illegal goals get by. That’s inexcusable.”

With eight of the 10 games at home, the Hawks went 8-2 over the stretch.

“Brian wanted to coach after that because he liked it so much, but he wasn’t a coach,” Peterson says today. “He was a GM.”

Two games after Hodge’s return, Portland unloaded on the Regina Pats — who would finish with a WCHL-worst 8-53-11 record — in a 15-1 win. It still stands as a franchise record for goals and is tied for largest margin of victory. The Hawks took a franchise-record 77 shots on goal and had four players notch hat tricks, both league marks at the time.

In that game, Babych scored two goals in five seconds — a WCHL record — and added a third, all in a span of 25 seconds. Babych, who finished with five goals, recalls the game clearly nearly a half-century later. The first two goals, he says, came with Mulvey in the penalty box.

“Brent and I have a plan off the draw in their zone,” Babych says. “He wins the draw, I grab the puck and get it in immediately. On the next face-off, Brent wins it again, gets it to me and I score, and the crowd is going crazy. Then we’re back at center ice and again Brent wins the draw. He gets into the zone and gets it to me and I score again.

“That was only 25 seconds, so we stayed on the ice. The next time, Brent again wins the draw, drops it to me, I take the (slap) shot and it hits the crossbar. Could have been four goals in less than a minute. I guess you could call it a great shift.”

Mulvey, who would lead the team that season with 251 penalty minutes — two more than Turnbull — served an early five-game suspension for various misdeeds. Turnbull was suspended for one game and fined $100 for accumulating five game-misconduct penalties.

“I’m not that much of a fighter, but it’s my first full year in the league, and I’ve got to show ‘em I’m not afraid of them,” he told me at midseason. “I guess usually I’ve gone into a game with a chip on my shoulder. I wasn’t going to let anybody do anything. I’ve changed now.”

Truthfully, Turnbull didn’t change much in that regard until his third season with the Hawks in 1978-79.

“Nobody wanted to battle with him,” says Jim Dobson, who played with Turnbull during his last season in Portland. “He beat up a lot of guys in the WHL.”

During Turnbull’s time in Portland, the most notorious fighter among the Bruins was Boris Fistric, a 6-3, 220-pound defenseman who logged 460 penalty minutes in 1978-79. That ranks fifth on the WHL single-season list for most penalty minutes.

“He wasn’t very interested in going with me,” says Turnbull, who tells a story about an incident at Queen’s Park Arena during his final season in Portland. “We had a line brawl. Boris was in the penalty box. I got into a fight with somebody over by the box. Boris reached over the boards and punched me. Once I got my arm free, he was standing there, and I just smoked him and knocked him down. From that moment on, he didn’t have a whole lot of interest in mixing it up with me.”

Keep in mind, Turnbull had great hockey skill, too.

“Perry was fantastic — big, strong and could skate like the wind,” Playfair says. “He was good with the puck, physical and tough. He got under the guys’ skin once in awhile, but that was Perry. That was just how he rolled.”

The reference was to teammates, not opponents,

“Perry would do fancy stuff in practice and piss the guys off, but he could pull it off,” Playfair says with a laugh. “He could skate almost like a figure skater. He would show off a little bit, and that would get under the guys’ skin.”

Peterson says Turnbull’s style was that of “a power forward along the lines of Cam Neely.”

Perry’s philosophy on the ice?

“I don’t know that I had one,” he tells me now. “I just went out and played, using the ‘Broad Street Bullies’ stuff that we had to do. Being a bully got you some more space on the ice. I guess my thought was, ‘Intimidate people and it will give me more room to make plays, because my hands aren’t that good and I’m not that smart.’ ”

The Hawks got their record to 18-16-2, then swooned on an 11-game, 17-day road trip, going 2-9. “It felt longer,” Playfair says. “That was nuts.” On that trip, Brian Propp scored seven goals against them in a 12-6 rout at Brandon — still an individual record for a Portland opponent.

Late in the regular season, Babych broke a hand but missed only one game, playing with a cast on the hand. He still reached the 50-goal mark.

“Innes would tape my hand to the stick,” Babych says. “I could shoot bullets, but never knew where it was going. I scored five goals in last two games to get my 50. For some reason, the puck was going in. With the cast on, I could shoot hard, but I couldn’t hit my six-inch target.”

The Hawks were aggressive on the road, but even more so at home, where they had become a very tough out.

“We didn’t back down, and that helped us in the long run,” Playfair says. “We took pride in making Portland a hard place to play when teams came in. They might beat us on the road, but when they came to Portland, they knew they were in a game. That gave all of us a bit of comfort.”

► ◄

Portland ended the 1976-77 regular season strong, going 10-2-1 over their final 13 games and 16-5-4 since the beginning of February to finish 36-29-7 and third in the West Division behind New Westminster and Victoria. There were routs of Winnipeg (16-4, scoring 10 goals in one period) and Lethbridge (7-0) and, in the regular-season finale, 10-2 over Victoria, with Currie registering a hat trick to run his total to 73 for the season, tying the club record by Darcy Rota in 1972-73.

The Hawks trailed 1-0 after one period and outscored the Cougars 10-1 over the final two frames, with much of the action happening after an on-ice brawl in the first period in which seven players from each team were ejected and a total of 221 penalty minutes administered. Among those given the heave-ho was Portland goalie Tim Thomlison, opening the door for 17-year-old Bart Hunter to make his WCHL debut. Hunter allowed just one goal the rest of the way, earning the game’s first star.

Yakiwchuk and Playfair missed the first two games of the first-round playoff series with Kamloops due to suspensions from the brawl against Victoria. Mulvey suffered a knee injury in Game 3 and was lost for the remainder of the postseason. Even so, Portland won the series 4-1, scoring victories of 7-0 and 5-1 in the final two games to eliminate the Chiefs.

New West beat Portland 4-1 in the West semifinals, claiming wins by scores 5-3, 2-1 and 3-2 in overtime. Turnbull played with a cast on a broken wrist. “It’s the playoffs,” he explained. “There’s no tomorrow. You just play.”

The Bruins were on their way to their third straight WCHL title and a Memorial Cup championship. They proved to be the Hawks’ nemesis during their first two seasons in Portland. It was especially tough for the Hawks to play them in their Queen’s Park Arena, a bandbox that was known not so affectionately by opponents as “The Zoo.” Or as Hunter called it, “The New West slough.”

“Every time we went in there,” Hunter says, “we expected a brawl. Nobody wanted to play there, but I looked forward to the games there. For us, they were a huge rival.”

“Never enjoyable for us to go in there,” Mulvey says. “It was a terrible exercise, playing in that depressing-looking old wooden barn.”

“They played in a little rink,” Turnbull says. “It was hard to just go in there and hit people, because you didn’t have any room to handle the puck.”

Even so, especially at home, the Bruins liked to “goon it up.” Babych and Peterson both use the word “scared” to describe how they felt when going against them.

“New West was better than we were at that style of play,” Peterson says. “They always tried to intimidate you. I was scared to death. They were a good team. Ernie was a good coach. They tried to run you out of their rink. Their arena was an absolute zoo on game night. They hung some of us in effigy in the stands.”

“I didn’t like them,” Babych says. “The physical part of the game in those days was a huge part. Their team was built on muscle. They had some really good players, were big and stuck up for each other. They used intimidation as part of their success. But we had a big team, too, and we stood up to them.”

The acquisition of Playfair helped change the dynamics, Peterson says.

“Larry was the reason we started standing up to Barry Beck and New West,” he says. “Larry had arms that crawled down like a gorilla scraping the ground. He was mild-mannered for a big man, but he was tough, boy. As soon as we got him, we were set.”

Well, at least better off. Queen’s Park Arena “was an intimidating place to play,” Currie says. “Nobody went into New West and liked it. You had a hard time not hating them. They were tough. It was a dirtier game in those days. But Beck, Mark Lofthouse, Brad Maxwell, Stan Smyl — they had a good team to boot. You couldn’t knock their skill. We might have gotten carried away. We had a big, tough team, too, and maybe we went at the game the same way to our disadvantage. They had a great power play and took advantage of our penalties a lot of times.”

“It wasn’t just New West, though,” Mackie recalls. “Teams from Alberta or Saskatchewan would come out on a Western road trip and play Friday in Kamloops and Saturday in New West or Victoria. When they would come to play us on Sunday in Portland, a lot of their guys showed up with black eyes. They were beat up.”

The Bruins were coached by Ernie “Punch” McLean, a one-eyed terror who was behind a terrible scene in a game against the Hawks two years later. When I ask Hodge today about him, he hesitates a few seconds before answering, “He was a character.”

A coach who instigated a lot of stuff?

“Yes, he did,” Hodge said.

Brown’s distaste for McLean’s teams resonates even today.

“What they did, that wasn’t even hockey,” Brown says. “Let’s not kid ourselves.”

“If you were playing for him, he was probably the best coach ever,” Lecuyer says. “Intimidation was a big part of the game, then, and you can’t argue with their results.”

Dobson played for New West before being traded to Portland in 1978.

“Ernie was a simple man with great demands as a coach,” Dobson says. “You better play hard. You better be tough. Finish your checks. And stick up for each other. If (the opponent is) messing with me, you better have all five on the ice getting in there. When I was there, it wasn’t just a bunch of goons. We had good talent.”

Babych played for McLean with Team Canada in the World Juniors.

“He was a good guy, a smart hockey man,” Babych says. “He knew what kind of team he had to build in New West to be successful, and he provided entertainment for the fans. It was always a tough place to play.”

The Portland-New West rivalry had just begun, but things were just getting started. And McLean was right in the middle of it.

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.