With those who knew Stan, it was a Love story

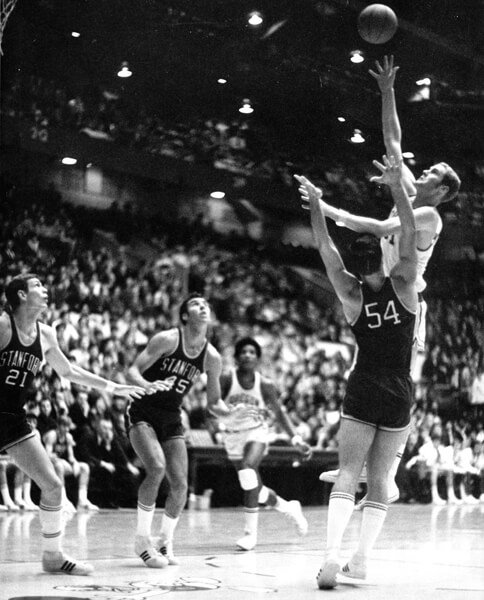

Stan Love was a two-time first-team All-Pac-8 selection and ranks second on Oregon’s career list for scoring average at 21.1 points per game (courtesy Oregon sports communications)

Updated 5/13/2025 1:10 AM

Soon after Stan Love turned 70 in 2019, I wrote a profile on the former Oregon basketball great for the Portland Tribune.

“I don’t feel 70,” Love told me. “Honestly, I never thought I would make it this far.”

Stan made it another six years. Two weeks after his 76th birthday, the younger brother of Beach Boys legend Mike Love passed away.

Two years before we did the interview, Stan was diagnosed with diabetes.

“I deal with it every day,” he said then. “But I feel good. Everything else is fine.”

In the ensuing years, Love was hit with cancer, then a heart attack.

“He got the triple whammy,” a friend says.

Stan died on April 24 at his Lake Oswego home, surrounded by his beloved wife of 39 years, Karen, children Collin, Kevin and Emily and five grandchildren.

“It was a nice ending,” says Mark Shoff, a close friend of Stan and Kevin’s coach at Lake Oswego High. “Family and his faith were the most important things in Stan’s life. He truly believed in family and God.”

Mourning the loss of Stan are a flood of friends and former teammates who liked him, admired him and considered him a prince of a guy.

“Stan was great,” says Jeff Kafoury, who did a radio sports talk show with Love for nearly a decade. “We hung out together for a lot of years. He was a lot of fun.”

I met Stan when I was a guest on their talk show on KXYQ (1010 AM) in the 1990s, and we became friends. For years, we spoke regularly on the phone, exchanged texts and discussed sports and music. Many times I sat with Stan — and sometimes others — in his party room or the backyard patio to watch on TV as Kevin played for the Timberwolves, Cavaliers or Heat. It was a holiday in the Love household in 2016 when Kevin and the Cavs won the NBA championship.

Stan set me up for an interview with brother Mike for a story I wrote on The Beach Boys for the Portland Tribune in 2013. I attended at least three Beach Boys concerts with Stan. At one of them, he got my wife, Steph, and me backstage passes, and we wound up dancing on-stage with family members during an encore song. That was a night to remember.

Over the last two years, Rob Closs and I brought sandwiches to the Loves’ home and had lunch with Stan several times. We always had a good chat, but he didn’t eat much. Said he didn’t have much of an appetite anymore. That was not good to see. But it was still good to be with him, if only for an hour or so.

At 6-9, Stan was an imposing figure, and he was no shrinking violet. But in his latter years, at least, I considered him a man with a gentle soul. A powerful guy with a soft approach.

“What is the saying — ‘A big man walking in soft shoes’?” Shoff says. “There was a peaceful kindness to Stan. I am sure his grandkids were able to see that.”

A poem carries this stanza that fits Stan well:

“He walks the world with measured pace,

A gentle giant, time cannot erase.

His power flows in a quiet way,

A strength that shines through every day.”

Of his former teammates at Oregon, Larry Holliday was probably Love’s closest friend.

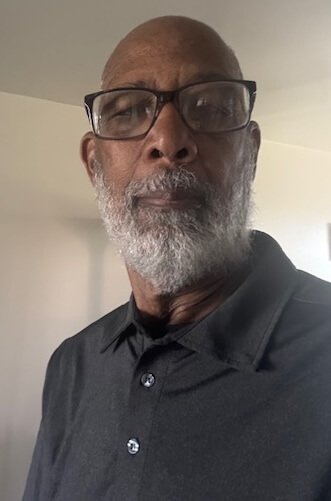

Larry Holliday, who started on the Oregon front line with Love for three seasons, says the thing he most appreciated about Love was “the commitment he maintained to being a good teammate” (courtesy Larry Holliday)

“We stayed friends all these years,” says Holliday, a starting small forward for the Ducks from 1968-71. “We respected each other. Through all these years, we always communicated.”

Holliday, who lives in Southfield, Mich., had stopped by the Love home on a 2023 visit to Portland. He noticed that Stan’s health was declining. It was the last time they would see each other.

Holliday was probably the last of Love’s friends to communicate with him. Both were April babies. Love was born on April 9, Holliday on April 13.

“We always wished each other a happy birthday,” Holliday says. “Our birthdays were coming up. In late March, I texted Stan, ‘Looking forward to turning 76.’ He didn’t respond.”

Holliday says he sensed something was wrong. But on April 15, he got a return text from Stan, wishing him a belated happy birthday.

Nine days later, Stan Love was gone.

► ◄

Love grew up in Baldwin Hills in West Los Angeles, the fourth of six children to Milt — a union sheet metal worker — and Glee Love. (One of his siblings, Maureen, lives in Lake Oswego and is a master harpist.) Brother Mike, now 84, was into surf music and started a band that went way beyond legendary.

“In our living room when I was growing up were a cello, a harp, a Steinway piano and other instruments,” Stan told me. “We would get together and sing. My mother pushed the arts. I watched opera at Hollywood Bowl when I was 12. I like music and I can carry a tune, but I don’t play any instruments.”

But Love played basketball, and very well. He signed with Oregon and coach Steve Belko his senior year at Morningside High in a recruiting class that included Holliday, Bill Drozdiak, Leonard Jackson and Rick Brosterhous. Holliday, who prepped at Dorsey High in Central LA, and Love came to Eugene for a recruiting trip on the same weekend.

“That gave us a chance to talk about getting out of LA,” Holliday says. “We played some pickup games and we played well together, and both enjoyed the trip to Eugene. We kind of decided on going to Oregon together. We talked about how we were going to integrate ourselves into the (Ducks) program. We built a relationship early on, not only in basketball but what we wanted to do in life, and how we wanted to represent.”

Truth be told, Love would have preferred to play his college ball in LA.

“For four years, Stanley played with a chip on his shoulder,” says Brosterhous, a guard from Klamath Falls. “He thought he should have been playing at SC or UCLA. He didn’t get recruited by either one of them and ended up at Oregon.”

Jim Henry, a 6-7 forward who led the UO Frosh in scoring during the 1966-67 campaign, was on hand when Love, Holliday and Drozdiak — out of Del Mar High in San Jose — came in for their visit.

“There were outdoor courts outside the dorms, and we played a lot of rat ball there,” Henry says. “We would take the recruits there and spend half the day playing hoops and seeing what they were all about.

“I didn’t know much about (Love). I thought he was good, but I remember thinking, ‘I don’t see what’s so good about this guy.’ That day, I thought I put it on him. And let me tell you, that was the last time I ever put it on Stanley.”

Bob Pallari was the team manager. He was with the group of players that day.

“We took Droz and Love into Mac Court to play, too,” Pallari says. “We were short a guy, so Belko had me fill in and guard Drozdiak. I had played high school ball, but I was no match. Bill had the best game of his life.”

Both Love and Holliday had to attend summer school at Lane Community College to fulfill entrance requirements at UO. Once they got into school, they joined a Frosh team that Brosterhous claims went undefeated during the 1967-68 season.

The 6-5 Drozdiak was Love’s roommate that freshman year. They became friendly enough that Love invited him to his parents’ home in LA for a weekend that year.

“Two big guys in a small dorm room, you get to know each other pretty well,” says Drozdiak, now an accomplished writer and author who lives in Washington, D.C. “I think (Oregon coaches) thought I would help keep Stan in line. I failed miserably at that task. He enjoyed a lot of rambunctious activity. He spent a lot of time goofing off. Fortunately, neither of us flunked out.”

Love was an immediate celebrity on campus.

“Everybody knew about his Beach Boys connection,” Drozdiak says. “He was a character and a naturally talented athlete. He was skinny, but he had incredible coordination. For a guy who was 6-9, he could dribble, he could pass, he could shoot. He had a smooth style to him.

“He worked on his shooting. It wasn’t that great to start with, but it became much better. He had very good technique.”

Says Henry: “I had set the freshman scoring record. Stan came in the next year and beat it. Was he super athletic? Not necessarily so. But he had will and grit, and that took him beyond his limitations. He was very competitive. That is what made up for any deficiencies he had.”

Love was Oregon’s best player as a sophomore, averaging 17.8 points and 9.5 rebounds on a team that went 13-13 overall and 5-9 in the Pac-8.

“We had been mediocre at best the year before, but when Stan and Bill came in, all of a sudden, we were a new team,” says Rick Abrahamson, a senior starting guard during Love’s sophomore season. “Stan was a force. He was fearless.”

Between his freshman and sophomore years, Love had played pickup games at UCLA against Bruin and USC players all summer.

“He came back in the fall, and you could tell he was ready to go up against anybody,” says Abrahamson, who would later gain notoriety playing for the U.S. handball team in the 1972 and ’76 Olympics. “He wouldn’t back down from anyone, not even (Lew Alcindor). We won the Far West Classic for the first time ever, which was a big deal.”

Love had the right mixture of swagger and humility.

Stan Love had an all-around offensive game in which he could score around the basket but also from outside (courtesy Oregon sports communications)

“He had the respect of the team right away,” says Abrahamson, who prepped at McMinnville High and now lives in West Linn. “He knew he was good, and we all knew he was good. He was a great player, but was also a good guy. He was very friendly. He was popular. Guys liked him. He had a good sense of humor. Smiling, never grumpy.

“I watched people stop him on campus to say hi. He would talk with them and have fun. He was the kind of guy we could be proud of, on and off the court. He was really a good guy in the locker room, but he changed when he went out on the court. Out there, he was such a fierce competitor.”

Sometimes a bit too fierce. Henry remembers a game against Washington when a Husky player tried to save a ball going out of bounds right by the Oregon bench. Love, out of the game at the time, “looked at the guy and stomped him on his head,” Henry says. “It is just the way he was wired.”

Then there was the time in Corvallis when Love made Vic Bartolome his foil, poking him in the eyes on a jump ball and later planting an elbow to the face of the OSU center, breaking his nose. For three years, Love was a villain in games at Gill Coliseum.

“Anybody who had a Beaver shirt on had nothing good to say about him,” says Henry with a laugh.

Adds Pallari: “There were moments that Stanley was a Draymond Green before Draymond, although he didn’t talk as much. It was all action.”

“Stan wasn’t the biggest center, so he had to learn how to play rough,” Holliday says. “If he could get an elbow in, he would do that. Sometimes it might be a teammate in practice. Our practices could get interesting, too.”

“Stan had his detractors,” says Henry, now living in Oregon City. “But I always had his back. The way I felt was, ‘You are talking to the wrong guy if you want somebody to bad-mouth Stan Love. I will never do it.’ I had nothing but respect for him.”

► ◄

Brosterhous roomed with Love on road trips for all three varsity seasons.

“Stanley was like no other,” says Brosterhous, who recently retired from his job as owner of a construction company in Eugene. “He was a wild and crazy boy. He had a lot of fun. Those were the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when if you couldn’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with. It was pretty much a party the whole four years.

“I loved every minute of it, and he did, too. He was a gregarious, fun-loving individual. I got pretty close with Stanley.”

Love told me he did enjoy his years at Oregon.

“It was a fascinating time to go to college,” he said. “It was during the Vietnam War, and we were all trying to stay in school so we didn’t get drafted.

“The Black Panthers were on campus, which was kind of fun. They liked me because I was the leading scorer — that got me some ‘cred.’ The music of that era was great. The culture in our society was changing.”

Though Love was popular with the opposite sex, “he wasn’t the playboy type,” Brosterhous says.

“Stanley didn’t go through the girls like a Larry Holliday, or me,” he says. “He had one girlfriend that I remember. He stuck with his pals, three or four guys from SoCal that he hung with. The black guys on the team lived in the same apartment building. That is where the parties were after every game. Stan would show up for those events.”

Those pals from SoCal might not have been the best influences.

“Stan was hanging out with a couple of the football players, Rocky Pamplin and Jack Stambaugh,” Drozdiak says. “Those guys caused a lot of mayhem — foolish, silly vandalism. Never serious enough to get in trouble with the law. They were bored, had a lot of excess energy and didn’t know what to do with it.”

“That is pretty right on,” Henry says of Drozdiak’s statement. “Stanley used to hang with those guys — Rocky, Stambaugh and Gordon Clay. Those three — not Stanley — would show up at a party and the girls would grab their purses and leave. Stanley got himself involved in a few small incidents, as did I, but nothing serious.”

While with the Los Angeles Lakers in 1975, Love collaborated with Ron Rapaport on a book titled “Love in the NBA.” In the book, Stan wrote that he and several Oregon teammates popped Dexedrine before many of the games.

“I found it was harder for guys to guard me when I was on something,” Love wrote.

When I asked him about that in 2019, Stan laughed.

“I said that?” he asked. “It might have been a little bit true. I was just trying to keep up with what was going on. You would play against UCLA and Sidney (Wicks) and Curtis (Rowe) would be foaming at the mouth and jumping two feet higher than usual. It was a sign of the times.

“I never smoked pot until later in life, but I knew there were some guys on the end of the bench — some very famous names — who were stoned to the gills watching from the front row. And if they got called to go into the game, it would have been … ha!”

I ran this by three of Love’s Oregon teammates.

Holliday is emphatic that, as far as he knows, Love’s assertions are untrue.

“No. No. I can say that from my heart,” Holliday says. “Dexedrine is not a drug that we just moved around or I was even aware of. We are talking about the ‘60s. I would be lying if I said people didn’t smoke weed. I would be lying if I said folks weren’t popping pills or hallucinogens. But doing that before playing? I was never aware of that, and I socialized with every player on our team. That wasn’t our lifestyle.”

Brosterhous, though, confirms Love’s account, or at least part of it.

“I was smoking pot, though I never smoked pot before a game,” he says. “But one thing I did do: We ate those bennies, those cross tops, before games. I am not going to say every game, but there were times when we would pop a couple of bennies. They just jacked you up. (The effect) was totally opposite of pot.”

Does he think any of his teammates smoked marijuana before games?

“No,” he says. “At least I never saw it.”

Henry confirms Brosterhous’ confirmation, and agrees with him on the pot issue.

“I never saw Stanley take any pills,” Henry says. “I knew some others were. That was going on in my senior year and Stanley’s junior year, but was it every game? I don’t think so. But there was some stuff going on, that’s for sure.

“I have no knowledge of anybody smoking pot before games. I started smoking pot in college, but never before a game. We were all smoking pot, but never did I suspect anybody was before games.

“It certainly wasn’t rampant. I’m sure if you write a book, you want to have some controversy in it. Some of that stuff was going on, but maybe not to the degree that Stanley insinuated.”

Love could be a prankster.

“He had this sick sense of humor,” Holliday says with a laugh. “We had this routine we would do when we played a team for the first time. Stan would go out for the jump ball to start the game. He would look their center in the face and say, ‘You ain’t s—t. I won’t waste my time. Larry, you jump.’ ”

Holliday, who was 6-3, could jump out of the gym. He was the designated jump-ball player all three seasons and says he lost a tip only four times — “three of them to (Alcindor).”

“But that was a good ploy by Stan,” says Holliday, noting that his teammate was working a mental game on the opponent.

Holliday recalls a moment at the end of a game against Washington State their senior year.

With the Cougars leading 68-67 and only seconds remaining, Love gets fouled.

“He is walking over to the free throw line and he says, ‘How you feeling?’ ” Holliday says. “I said, ‘I feel all right.’ He said, ‘You feel like playing overtime?’ I said, ‘No, Stan. No.’ If I had said ‘Yes,’ he might have said, ‘Fine. I’ll miss; let’s play some more.’ ”

Love made the free throws. Oregon won 69-68.

“Stan was a great teammate,” Holliday says. “He had your back. He was very determined in his play. He was a center who played with his back to the basket, and he had a nice hook shot, though he also had a very good outside shot. He would have developed a 3-pointer as good as his son if the 3-point line was there at the time.”

As a junior, Love averaged 20.8 points and 10.7 rebounds. That was the season when the Ducks upset No. 1-ranked UCLA 78-65 in the Pit. Love and sophomore forward Rusty Blair led the way with 19 points apiece.

“For us to beat UCLA was phenomenal,” Holliday says.

“It’s a night I’ll never forget,” Brosterhous says.

“Stan was a really good big-game player,” says Bob Rodgers, a reserve guard who played two seasons with Love. “He was a much better game player than a practice player.”

“He was an unreal player, an amazing talent,” Brosterhous says. “He was a center, but he could bring the ball upcourt. He could fill the lane on a fast break like a guard or forward.”

As a senior, Love was even better — 24.6 points and 11.3 boards per game. Both years, the Ducks were 17-9 overall and 8-6 in Pac-8 play. He was named first-team All-Pac-8 both years, joining such players as Wicks, Rowe, Paul Westphal and Phil Chenier.

Love held Oregon’s single-season scoring record for 20 years, recorded the Ducks’ highest mark ever (27.3) in conference games and ranks second in career scoring average (21.1) behind only Terrell Brandon (22.2). He still is tied for eighth on the school scoring list despite playing only three varsity seasons.

There was another thing.

“Stanley never missed a varsity game in his three years at Oregon,” says Henry, who has owned and operated Aloha Juice Company for 35 years. “He always showed up.”

“Stan had a great reputation as a player in the Pac-8,” Holliday says. “The main thing is the commitment he maintained to being a good teammate. He never acted like he was any better than anyone. We all got along very well. We worked together and were committed to what we were doing.”

► ◄

The Washington Bullets chose Love with the ninth pick in the 1971 NBA draft and signed him to a four-year, $460,000 rookie contract. Love played two seasons for the Bullets and a season and a half with the Lakers before being released midway through the 1974-75 season. He played 12 games with the San Antonio Spurs of the old ABA, then played three-quarters of a season professionally in France before retiring as a player at age 26.

The list of Love’s teammates during his short pro career reads like a “Who’s Who” in NBA history, including Jerry West, Wes Unseld, Elvin Hayes, Earl Monroe, Gus Johnson, Gail Goodrich, Connie Hawkins and Pat Riley. All are members of the Naismith Hall of Fame.

Love had a solid rookie season with the Bullets, averaging 7.9 points and 4.6 rebounds while playing 17.9 minutes a game. His production and playing time went down every season, however, and he never cracked a starting lineup.

“I was on teams with some super players,” he told me. “You can’t put Elvin Hayes or Wes Unseld on the bench so I can play. In retrospect, I should have gone to the ABA, or to a crummier team where I could play more. I was with top-tier teams featuring All-Stars and Hall-of-Famers.”

Love was regarded as a free spirit during his NBA days. He wore a high Afro and handlebar mustache and was referred to by one publication as “playboy of the NBA’s Western Conference.”

With his brother playing for The Beach Boys, Stan gained a reputation as a surfer dude — he was a surfer dude — who happened to play basketball. Did that affect his career?

“I think it did,” Love said. “It had a lot to do with my brother being in rock-and-roll and the Hollywood thing. (Coaches) weren’t ready for it.”

After retiring as a player, Love toured the world with the Beach Boys for five years in two different stints in his late 20’s and early 30’s. He essentially acted as a bodyguard and caretaker for Brian Wilson, who was Love’s cousin. Wilson dealt with groupies and drug problems and hangers-on who wanted to rub shoulders with a celebrity.

“Those were chaotic years,” Love said. “It was 24 hours a day of worrying, trying to keep the creeps away. Fame and money and rock-and-roll — it is all a very dangerous area to live in.”

During that time, Brian’s brother Dennis — another member of the band — was supplying him with cocaine. That did not sit well with Love and Pamplin, who was also working as a caretaker with the group. Posing as police officers one night, they busted into Dennis’ house and laid a brutal beating on him. Love was eventually fined $750 and put on six months of probation over the incident. He felt it was worth it.

“Do you think Dennis got the message?” Love asked rhetorically. “Brian is a very fragile individual with a lot of mental challenges. For someone to give him access to cocaine — that pissed me off. People get what they deserve. Dennis was one of the most problem persons I have come across.”

Shortly after Stan and Karen married in 1986, they moved from Southern California to Oregon to begin raising a family, and life settled down for Stan.

“For three or four years, we played AAU basketball together in the Portland area,” Abrahamson says. “He liked to spot up and shoot the long ball. He would also take it to the hoop and drew the foul.

“Stan was the whole package. He should have played five to eight more years in the NBA. The story I heard is that he was playing summer league for the Lakers and didn’t show up for a couple of weeks. He explained that he didn’t feel like playing summer ball, that he was making more money working for The Beach Boys. I can see him saying that.”

In Portland, he worked a few years for United Salad, neighbor Ernie Spada’s business. He had his radio gig with Kafoury for a spell. Karen, meanwhile, had a long career as a nurse.

Pallari eventually became president of Legacy Health in Portland.

“Karen worked as a nurse Randall Children’s Hospital at Emanuel,” Pallari says. “She is a great person. So was Stanley. He was always respectful and just a solid guy. I loved him dearly.”

Pallari recalls getting together with Love in Portland when he was playing for the Lakers.

“I was newly married and had a one-year-old child,” says Pallari, now living in Camas, Wash. “When they came to town to play the Blazers, he contacted me, came over to see me at our little duplex and got tickets for me to come to the game. He never forgot. He was loyal. If Stanley was your friend, he was always going to be your friend.”

Holliday confirms that. He recalls an incident the year after their college days, when Love was a rookie with the Bullets and Holliday was trying out with the Miami Floridians of the ABA. As luck would have it, the teams played an exhibition game against each other.

“Stan got injured before the game and had to be taken back to the hotel,” Holliday says. “The young man who gave him a ride was the son of our owner. Stan asked him how I was doing in camp. Before he could answer, Stan said, ‘If he doesn’t make the team, I’m gonna come back at you.’ ”

Love was kidding around, but “there was always a commitment to our friendship,” Holliday says. “That never changed.”

Years later, during Kevin’s lone season at UCLA, Kafoury traveled with Stan to L.A. to watch him play.

“I ended up staying with him for a couple of weeks there,” Kafoury says. “He showed me the house where he grew up, where The Beach Boys got started, where he went to school, where he would go to work out, his hangouts. He introduced me to a bunch of fantastic people. And we got to see Kevin play.”

► ◄

Stan saw something special in Kevin, his middle child, as an athlete. Stan was his first coach, teaching him how to play, how to think the game of basketball.

“Stan worked with Kevin a lot, especially on the nuances of rebounding from the time he was seven, eight, nine years old,” a family friend says. “A big part of Kevin’s game was the result of the time Stan put in with him.”

Kevin was a man among boys playing basketball through youth ball and started for the varsity as a freshman at Lake Oswego High. At first, Stan and Karen took issue with Shoff, the coach. They thought Collin — a year older than Kevin — merited a more prominent on-court role than he was getting.

The bigger issue, though, lay with Shoff’s rules regarding missed practices. School regulations stated that a player who missed class couldn’t attend after-school practice sessions. Shoff, in turn, said players who miss a practice couldn’t start the next game.

About three-quarters of the way through his freshman season, Kevin came down with mononucleosis. Because he stayed home from school, he couldn’t practice, and therefore didn’t start the next game.

“Kevin wouldn’t start, but he would still play,” Shoff recalls. “As soon as I could get him in the game, I did. I wasn’t going to leave Kevin on the bench more than a couple of minutes, but Stan was upset with that.”

The next day, Stan visited school and began pasting “Fire Shoff” stickers around the gym. When Shoff called Kevin into his office to inform him of his father’s behavior, Stan hired a lawyer, who took out a restraining order forbidding the coach from communicating with his son, or talking about him to media or recruiters. He then threatened to transfer Kevin to another school unless Shoff was fired.

Shoff wasn’t fired, and things settled down. Kevin stayed at Lake Oswego. Before the next season, Stan approached Shoff.

“Hey coach, I owe you an apology,” he told Shoff. “I was dead wrong and immature and said some things I shouldn’t have. I apologize.”

“From that point on, Stan and I got along really well,” Shoff says. “He was real. A lot of people don’t like to be told the truth. Stan wasn’t afraid to tell the truth. With that, he sometimes got misread. As he got older, he got more wise as far as what would come out of his mouth.”

Kevin became the most celebrated prep basketball player in the state’s history. He teamed with South Medford’s Kyle Singler and Jesuit’s Seth Tarver to form a summer AAU team that won several national tournaments. The Lakers beat South Medford for the state championship as a junior; Singler and the Panthers got revenge and won it their senior year. Kevin was named the national Gatorade Player of the Year.

During his one season at UCLA, Kevin led the Bruins to the Final Four. He was a consensus first-team All-American and was named Pac-10 Player of the Year. His professional career has been outstanding. He is a five-time All-Star, a two-time member of the All-NBA Second Team and a member of the U.S. team that won gold at the 2010 World Championships and 2012 Olympic Games. At 36, he is in his 17th NBA season, the last three with the Miami Heat.

•

As Stan’s health deteriorated, Kevin left the Heat in late March and returned to Oregon to be with family. He was there until the end, missing Miami’s entire playoff run.

Kevin was estranged from his father in recent years, but the wounds were healed in their time together in the final weeks of Stan’s life.

“Over the years, my dad and I had our differences,” Kevin wrote in an Instagram post three days after Stan’s death. “I mourn the times I felt angry and isolated. My heart weighs heavy knowing we lost that time and can’t get it back. But our division led to me finding myself. I was running from something. But that time away provided the wisdoms of forgiveness and reconciliation, and an unwavering sense that he loved me through it all, in every moment.”

Kevin paid tribute to Stan as “my greatest teacher.”

“You taught me admirable qualities like respect and kindness,” he wrote. “Humor and wit. Ambition and work ethic. Grit and aggressive will. The insight that failure brings, and that time is our most precious commodity.”

Kevin added a saying in quotations: “The best last lesson one generation can teach the next: How to die with peace about how you’ve lived.”

“This may be my dad’s greatest gift,” he wrote. “Teaching me that healing happens in your soul and that healing is there for the taking, even in the face of imminent death. Dad loved his family unconditionally and left his children with one of life’s great lessons.

“Like all of us, my dad was imperfect. But despite his flaws, and my own, we are a successful story of father and son. A never-ending bond, rooted in love, that will forever remain eternal. And even at the end … I still saw you as a Giant. My Protector. My first Hero.”

Mike Love also weighed in on Instagram. His message, in part:

“My big younger brother, you called me the superstar, but to me you are the superstar!! You always had my back! I am blessed to be your brother. I will cherish our lives spent together, whether spoofing on each other or reliving memories. I know you’re on the big court now, pounding down 3’s; don’t foul out, bro. Give Mom and Dad a hug from me. Until we meet again, I love you, Brother, for eternity.”

At Stan’s request, there will be no memorial service or celebration of life. So let this story serve as a tribute to a man who achieved much and had a great impact on those he touched.

“Stan was larger than life,” a friend says. “You could live 100 lifetimes and never meet another Stan Love.”

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.