Spartans give Donny Reynolds his due

From left, Jan, Simone, Donny and Isaac Reynolds during the halftime ceremony

Updated 9/18/2025 1:21 AM

CORVALLIS — Oh, you should have heard the cheers.

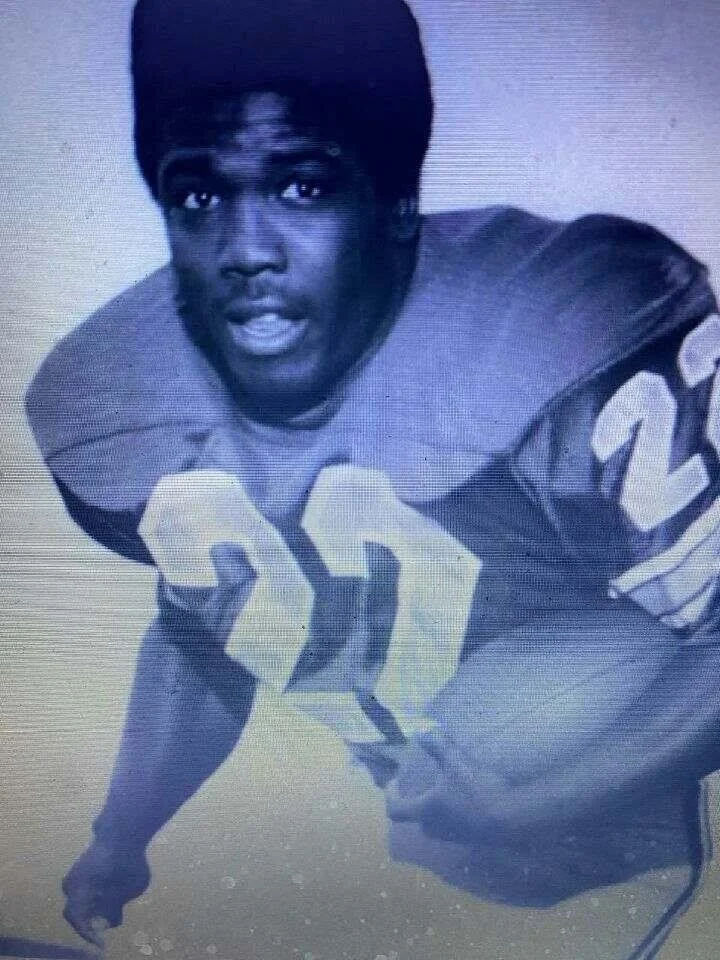

Donny Reynolds had heard them before, from football and baseball fans at Corvallis High, the University of Oregon and with various teams in pro baseball through the years.

But Friday night’s ovations as his No. 22 football jersey was retired at his prep alma mater may have been the most meaningful of them all.

Reynolds was honored during halftime of the Spartans’ 44-12 rout of intra-city rival Crescent Valley. About 30 former CHS athletes and students — many of them teammates and classmates of the legendary halfback — and several family members were on hand to help him celebrate his big night.

“I am humbled by this,” Reynolds told the large crowd of CHS students and their parents. “It is so great to have all of you here, but especially my friends, teammates and family.”

Prior, in an interview with me, Donny related, “I feel a little bit embarrassed by the eyes on it. It is a great honor, but it is really an award for our entire team.”

Reynolds joins fellow septuagenarians Mike Riley and Gary Beck as the only football players who have had their numbers retired at Corvallis High. The trio led the Spartans to the 1970 state AAA championship.

From left, Gary Beck, Mike Riley and Donny Reynolds. Donny’s No. 22 will hang alongside those of Beck and Riley

Beck, a safety and placekicker, wore No. 10. Riley, the quarterback, wore No. 12. It is ironic but also fitting that the numbers 10 and 12 add up to 22.

“I told Mike and Gary some time ago, there is no No. 22 without you two,” says Reynolds, 72.

Reynolds’ younger brothers of considerable renown were on hand.

Larry Reynolds, a two-sport standout at Stanford who played six years of minor league baseball, flew in from his home in Riverside, Calif. Larry, 68, a four-year starter as a shortstop and outfielder in baseball, was the Pac-8 MVP as a junior and a second-team All-American as a senior. He was a four-year starter in the secondary in football. Larry has worked since 1984 as a player agent and is currently president and CEO of Reynolds Sports Management, representing MLB and minor-league players. “I’m still working, but I’m easing out,” he says. “I’m mostly a consultant now.”

Harold Reynolds, a two-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glove winner across 12 major league seasons, arrived from his home in Montclair, N.J. After his playing days, Harold, 64, has distinguished himself through three decades as a broadcaster. He has won four sports Emmys and currently works as a studio host on MLB Network.

Donny’s wife of 37 years, Jan, was there along with son Isaac, 26, who lives with them at their home in Arch Cape on the northern Oregon Coast. Daughter Simone Reynolds, 30, flew in from her home in Los Angeles for the event.

While Donny was being honored, film clips of his playing days at Corvallis High were shown on the scoreboard.

“That’s the first time I have ever seen (film of) him playing football,” Simone says. “That was fun. It was really cool to see how many people came up and asked him to sign magazines and (trading) cards. They told him how much they thought of him.

“It was a beautiful testament to his legacy in Corvallis. I was happy he was able to experience this special moment.”

Donald Edward Reynolds is a modern-day Horatio Alger. (Most everyone calls him “Donny” except his family members). It is truly a rags-to-riches story.

Donny was the oldest boy and fourth of eight children raised by a divorced mother, Lettie, now 94 and in assisted living care in Dallas, Ore. He had three older sisters and four younger brothers. (Tim, the next-to-youngest son, died in 2024 at age 65. Ron, the middle son, lives in Corvallis.) They lived in a three-bedroom, one-bathroom house on “A Street” across the street from Parker Stadium and Gill Coliseum.

Through her children’s formative years, Lettie cleaned neighbors’ houses, held jobs at Wah Chang Corporation in Albany and at Adair Air Force base. The family received federal assistance at times, including food stamps, but it was always a struggle financially.

“My mother had to do a lot of odd jobs just for us to survive,” Donny says.

“She took care of us in a way that, not having a lot, we all felt that we had a lot,” says Janice (now Janice Lewis), the oldest of the children. “Mom was very resourceful. She didn’t sit around waiting for anything to happen. She always made it happen herself.”

“What a wonderful person Lettie was, and what a wonderful job she did with all those kids,” says Chuck Solberg, who coached four of the Reynolds boys at Corvallis High. “They should retire her number, too.”

Donny was born in Arkansas but moved to Eugene with his family when he was six months old. In previous years, Lettie had spent time in Eugene caring for her great aunt. There she met John Reynolds, whom she eventually married.

“That is a whole documentary in itself,” Harold says.

Lettie and her growing family were also able to be closer to her mother, Toreacy (pronounced “Theresa”) Hoskins, who lived in Eugene.

John was the biological father for all of Lettie’s children except Janice. Lettie and John divorced, and Lettie moved her family to Corvallis in 1963, when Donny was 10 and in the fifth grade.

“My father was an abusive man, and my mother escaped from that abuse,” Donny says.

Abusive to Lettie, or to all the family members?

“He was abusive,” Donny says. “He was a rough individual. One day (Lettie and Toreacy) packed us up and moved us out of the house, and disappeared from him. She needed to get away. That move saved her and saved us.”

From that point on, the children saw little of their birth father.

“He spent Christmas with us a couple of times,” Donny says, “but there was minimal contact with him.”

Why did Lettie choose Corvallis?

“It’s real simple — so she could have a hand on us,” says Harold, who was three years old when the family made the move 40 miles north. “Eugene was bigger. Corvallis was a small town (20,000 in 1960, 40,000 by the time Harold graduated from CHS in 1979, 62,000 today). Her thinking was, ‘I can have my hands on them and be able to know what they are up to all of the time.’ ”

“It ended up being the best choice she ever made,” Janice says.

Janice was 15 when the Reynolds moved to Corvallis. She stayed behind to live with her grandmother and graduated from Sheldon High, though she spent the summers in Corvallis and visited the house often during the school year.

Religion was a foundational piece of the Reynolds family. They attended the Foursquare Church in Corvallis.

“We grew up in a Christian home,” Donny says. “Church was a big part of my childhood. My belief in God and Christianity is something that has carried over from my youth to my life now.”

During the kids’ formative years, the living arrangements at the house on A Street were crowded, to say the least. There were two bedrooms upstairs and one downstairs, the latter where Lettie slept. Until Donny’s sophomore year at CHS, all five boys slept in the master bedroom, “with a couple of big beds in there,” he says. The girls, Sharon and Debbie, shared the smaller upstairs bedroom. When Sharon graduated after Donny’s sophomore year, he shared a bedroom with Debbie, “with a sheet hanging up to divide the room,” for a year. After Debbie graduated, Donny got the room until he graduated in 1971.

Chaotic? “Always,” Donny says with a laugh. “But we all got along.”

Says Larry: “It was every boy and girl for themselves as far as eating and sleeping. We managed.”

Lettie was a bit of a miracle worker.

“Looking back at it, it’s like, wow,” Donny says. “Just trying to get two kids from birth to grownup is hard, and I did it with a wife. For her to raise eight kids was incredible. What a strong lady.

“She did everything for us. She sacrificed so much for our family. We were her life. It’s amazing how strong and determined she must have been and how willing she was to do what she had to do for our family. The lady gave her life for us.”

As the youngest, Harold spent more time with his mother than any of the children.

“The greatest attribute she had, she never made anybody feel like they were less special than the others,” he says. “That is a unique talent. She didn’t play favorites. That laid the foundation for a lot of things.”

The other major influence was grandmother Toreacy.

“Our mother’s resolve goes back to my grandmother and her side of the family,” Janice says. “There were very strong women on her side of the family, very determined to do things and get them done the right way.”

“The determination to get things done went right from our grandmother through my mom to the kids, no question about it,” Larry says. “It was a package of two people who influenced all eight kids.”

“It was good cop, bad cop,” Harold says. “Grandmother was the enforcer. She made sure that you did not get out of line. I was real fortunate to have been raised by those two.”

“My grandmother had no book learning, but just plain wisdom,” Donny says. “She was intuitive. She knew when things were going on with us. Such a strong figure. My mother leaned on her a lot. My mother’s strength came from her. She had many of the same qualities. My grandmother didn’t ask you to respect her; you just respected her because of who she was. Such a strong influence on my life. She was the backbone of the family.”

Donny has another thought.

“I shouldn’t leave out my sisters,” he says. “They helped me stay on a straight line. They protected me and defended me.”

Donny’s younger brothers look at him the same way.

“Whatever we needed done to help the family, Don was the lead dog,” Larry says. “We looked up to him. He did a lot by example. We didn’t have a father in the house, so Don was both older brother and father. He was a great mentor and leader. He looks out for us to this day. He cares about the family tremendously.”

“Don was my hero,” Harold says. “Growing up without a dad, Don took on that father figure role. The way he carried himself in my developing years was the standard for how I wanted to be. Don knew he had to be the leader of the pack. He took me under his wing. He did that to an extent with all the boys.”

The Reynolds were one of the few black families in Corvallis in the 1960s and ‘70s.

“We got a lot of looks from neighbors when we first moved in,” Donny says. “Curiosity, I think. Most anybody who was black and living in Corvallis at that time was either attached to the university in some way or to Adair Air Force base. We were neither. It was an interesting time, but it was also a great time.”

The Reynolds ran into their share of racism, especially in the early years. As the youngest, Harold believes he was shielded from the brunt of it.

“Don, Larry, Ron, Tim, the girls — they all paved the way for me,” Harold says. “They all had different battles with racism. By the time I got to high school, though, the family was cemented into the town. (His siblings) knocked down a lot of walls. Not that I didn’t run into things, but it wasn’t nearly what they went through in the times they were in.”

“I felt comfortable around the Reynolds family and never thought about the fact that blacks were in such small numbers in Corvallis at the time,” says Jerry Hackenbruck, a tight end/defensive end who also played basketball with Reynolds. “That might have been tough for Donny, but I think he was also lucky to be in a town like Corvallis, because he had so many friends. People were drawn to his abilities, but once they got to know him, they learned what a great person he was. Everybody loved him. He was one of the most popular people in that high school.”

All of the Reynolds kids were personable and among the most popular in their classes during their school years. As the years went on, they weren’t only accepted by the community, they were cherished. Community members looked out for the Reynolds as they were growing up.

“Lettie was an incredible mother, but the whole town of Corvallis raised the Reynolds family, too,” says Dave Roberts, who was the same class as Sharon and two years ahead of Donny. “There was that ‘it-takes-a-village’ thing.”

“I was extremely fortunate to grow up in a place like Corvallis,” Donny says. “That is what I can always refer to when I look back at my life. The strength of that family feel in the community is the core of my being.”

Lettie — and the girls as they got older — became friends with some of OSU’s minority students. Often they would get invitations to spend a holiday at the Reynolds’ home.

“We did a lot of entertaining that way,” Janice recalls. “We were like a draw to the college students.”

Living quarters may have been tight, but the location was supreme, at least for the boys in the family who had a sports playground across the street in Parker Stadium and Gill Coliseum.

“We got to go to all the Oregon State games,” Donny says. “We saw all the great teams play in Parker and Gill. We experienced a lot of things because of the university right next to us. For kids who loved sports like we did, I can’t think of anything better.”

Most of the time, they didn’t have game tickets. But like many of their friends, they found ways to sneak through gates at Parker and locked doors at Gill.

“We had a key to everything at Oregon State, let’s put it that way,” Donny says with a laugh. “We could pick any lock they had.”

Well, figuratively, at least. As they got older, they found ways into Parker for pickup football games, or into Gill for some half-court three-on-three. And of course, there was always time for some fooling around. Harold’s best friend as a youngster was Kurt Kemp, who would go on to become director of player development for the Atlanta Braves.

“Kurt and I would wrestle Don all the time,” Harold recalls. “We would pin him down. They he would hit us with monkey bumps on our shoulders. Man, those hurt.”

The Reynolds boys were among the best, if not the best, athletes in town. Sports was a unifying activity for the Reynolds boys and their friends.

“We didn’t know any better,” Larry says. “We went out and played sports and kept it moving. That’s pretty much how we grew up.”

The younger Reynolds boys had the advantage of a built-in coach.

“Don was always there to help coach us,” Larry adds. “He wanted us to learn how to hit the right way, to hit the ball all over the field. Learning how to hit with that group of guys from Corvallis, like the Becks and Roberts, was really fortunate.”

“Those were like the golden days for a little kid like me,” Harold says. “I was hanging around Don and his friends all the time. Even when I was in the major leagues, he would be coaching me when I came home (to Oregon). He was a major influence from childhood on.”

Donny’s friendship with Beck began in fifth grade.

“I met Donny at Avery Park the summer of ’63, my first year in Pee Wees (baseball),” says Beck, who would go on to play football and baseball at Oregon State and to coach Corvallis High to a pair of state 3A football titles. “We were both on the Boa Constrictors. I wanted to play shortstop. The first day, I asked what position he was playing. He said shortstop. I immediately became a second baseman.

“We did a lot of things together, because we enjoyed playing a lot of sports. We played Wiffle ball in my backyard. We would play basketball in Gill and two-on-two football games on the practice fields at Oregon State. We shared a common love. Sports were a binding activity in our lives.”

In high school, Donny and Gary added Mike Riley and Dean Roberts to their “best friends” list. Riley would go on to fame as a football coach, including a three-year stint as head coach of the San Diego Chargers. Roberts was an All-State basketball player at Corvallis High, a two-sport star at Oregon and later a long-time basketball coach at West Albany High.

The quartet formed the Mount Rushmore of athletes in the CHS class of ’71. They attended Fellowship of Christian Athletes and Young Life meetings together. They set the tone for the Spartan athletic teams of that era.

“We were all pretty close,” Donny says. “The four of us hung around more than anybody. We did so many things together. It wasn’t just the athletic stuff. It was their friendship that meant the most.

“But it wasn’t just us. Our class had a special group of people. You could trust them, you could count on them, you knew they had your back. It was a very cool thing to have as you went through the challenges of high school.”

During Reynolds’ junior year, Corvallis reached the state 3A football championship game and won the state title in basketball, becoming the first team ever to go through a season undefeated. The following summer, Reynolds was a member of the Corvallis team that won the state American Legion baseball title. During his senior year, the Spartans won state championships in football and baseball. That is four state titles in a 15-month period.

“That had such an effect on me during my developing years as an adolescent,” Harold says. “Being able to watch those teams turn the whole scope of Corvallis sports around gave me ambition beyond what I could have imagined. I don’t sit in this seat today, having been a pro baseball player, without growing up in Corvallis.”

Riley likes to tell the story about rooming with Reynolds for the American Legion Regionals in Roseburg in 1970.

“We’re at our motel waiting for our Saturday morning game,” Riley says. “We’re up and ready to go. Suddenly, it seems quiet. We look out in the hall and nobody’s around. We knock on doors of some rooms; nobody’s there. We grab our stuff and go running down to the lobby, and the team is gone. Nobody ever knocked on our door. They just jumped on the bus and left. We had never been late for anything.”

Somebody gave the duo a lift to the ballpark.

“We see our teammates warming up on the field, and we are scared to death,” Riley says. “We sit down in the dugout. Pretty soon (manager) Bob Clark comes over and says, ‘If you’re going to play, you better put your cleats on.’ We did, and we played.”

Reynolds laughs at Riley’s version of the story. The players were supposed to meet in the lobby at a certain time that morning.

“We knew about it,” Donny says. “Saturday morning was cartoon day. Bugs Bunny was on. We were watching cartoons.”

► ◄

Lettie Reynolds with her young sons, from left, Harold, Tim, Ron, Larry and Donny (courtesy Reynolds family)

Donny didn’t have a father in his life, but he had plenty of father figures. He mentions Chris Leston, his coach at Western View Junior High; high school coaches Solberg, Glen Kinney, Carl Hutzler and Chris Christianson; and Bud Riley and Wayne Roberts, fathers of Mike Riley and Dean Roberts.

“The adults around embraced me — the mothers, too,” Donny says. “Collectively, they gave me great role models.”

As a sophomore, Donny played only four football games with the Corvallis High junior varsity because of a heart murmur. (The condition would cause him plenty of humorous “grief” from teammates the following two seasons as he sat out of many sprint drills at the end of practice sessions). As a junior, a new coach came to the school. Solberg took over a team that had gone 3-6 in 1968 and guided the Spartans to the state championship game, where they lost 27-0 to Medford.

In his second varsity game in 1969, Donny couldn’t have exploded onto the scene in a bigger way, scoring the game-winning touchdown on the final play of a 20-15 victory at Medford. It came after some consternation on Reynolds’ part. Prior to the TD, Reynolds had missed an assignment while playing cornerback with Corvallis nursing a 13-8 lead in the final minute. Ray Peterson threw a five-yard pass to Bill Singler for a score and a 15-13 lead with three seconds to play.

When Reynolds came to the sidelines, “(assistant coach) Doug Bashor got in my face about it. It embarrassed and upset me. I was hoping (the Black Tornado) would send the ensuing kickoff to me, because I believed I could return it and we would win.”

Instead, an onside kick traveled only nine yards, taking no time off the clock. Riley threw a screen pass to Reynolds, who took it 49 yards for a touchdown as time expired.

“We didn’t even lay a hand on him,” says Scott Spiegelberg, a junior who split time with Peterson at quarterback that season. “I thought, ‘whoa.’ We were in shock.”

“Watching from behind as he ran to the end zone — I had the best view in the house,” Riley says with a laugh. “That was the coming-out party for Donny. You could just see it.”

“It was unbelievable,” Reynolds says now. “A couple of (defenders) missed and things just opened up. As I was running down the (Medford) sidelines I thought I might get Dick-Hartered.”

(A great line by Donny, the reference to the incident in which former Oregon basketball coach Harter tripped OSU cheerleader Rick Coutin as he paraded the Chancellor’s trophy around the Gill Coliseum court in the closing minute of a Beaver win.)

The Spartans’ success on the gridiron that season “set the tone for the rest of my athletic career,” Donny says. “Chuck taught us how to work hard, and to work harder. He expected 100 percent effort, and that’s what we got from him, too. It carried through to my college years of football.”

Reynolds’ senior season was spectacular as he helped lead Corvallis to an 11-1 record and revenge over Medford in the state championship game with a 21-10 victory.

“Donny was a leader — not so much vocally, but in how he handled himself,” says Hackenbruck, who would go on to become a second-team All-Pac-8 defensive end and co-captain at Oregon State as a senior in 1974. “Mike wasn’t an outgoing guy, either, but he commanded the huddle. He was our leader, and Donny and Gary were also leaders. The rest of us grunts just did our job and helped make the team what it was. Being able to play sports through those years with Donny was a great experience.”

The other OSU co-captain that year was center Greg Krpalek, who with Albany High lost three of four meetings with Corvallis during Reynolds’ two seasons of varsity football.

“I first saw Donny when I was at Memorial Junior High and we played Western View,” Krpalek says. “After our game, I went home and told my mom, ‘I just went up against a player who is going to be incredible.’

“And look what he did. Donny was an incredible athlete, and God could he run. He was hard to stop. That was the difference in our games. He was always the key guy. Corvallis had a great team, but he was the one who made things happen.”

Solberg’s teams employed a full-house backfield and averaged single-figure pass attempts per game. The 1970 Spartans were a machine running the ball, however, with Reynolds and fullback Darian Morray — who rushed for 1,073 yards and 19 touchdowns in 10 games — carrying the load. But Morray was injured early in the first playoff game at Sunset and Reynolds took over the rest of the postseason.

“He was so freaking explosive,” Harold says. And never more so than in the ’70 playoffs.

“Donny put us ahead in every quarter of every playoff game with a run from outside of 50 yards,” Solberg observes.

The quarterfinals matched the state’s No. 2-ranked team, Corvallis, against No. 1 Sunset. (There was no seeding in those years). Reynolds broke loose for touchdown runs of 62, 73 and 50 yards in the first half, sparking the Spartans to a 28-6 lead en route to a 42-12 rout. He finished with 200 yards on just 12 carries.

Reynolds scored two touchdowns, including a 73-yard scamper, in a 20-14 victory at Pendleton in the semifinals. He carried 16 times for 160 yards in the game.

“I’ll never forget that long run,” says Dean Fouquette, the Buckaroos’ quarterback that season. “He just broke through the line and was gone. He was a big-game player.”

Reynolds made his mark in the championship game rematch with Medford, scoring on a 69-yard run off an option play for the Spartans’ first touchdown. He ran the ball 13 times for 110 yards against the Black Tornado.

“Mike was Mr. Deception on the option,” Spiegelberg says. “With his fakes, we had trouble knowing where the ball was. When it got into Donny’s hands, we were in trouble.”

Reynolds finished his senior season at Corvallis with 1,277 rushing yards for a 9.5-yard average. In three playoff games he ran 41 times for 470 yards and an 11.4 average.

“When you get in the playoffs, you are going up against good teams and it is hard to put together a 10- or 15-play drive,” Beck says. “To be able to hit a big play like Donny did sucks the life out of the defense. It’s disheartening. He had so many long ones.”

It helped that four of Corvallis’ starting offensive linemen that season — center Ken Maddox, guard Mark Duff and tackles Dave Woelfle and Steve Martinson — were either first- or second-team all-league players.

“Donny had some good linemen blocking for him,” Beck says. “Smart guys. They knew who to block, they knew how to block, and they did it. Solberg’s offense was so repetitive, we got really good at what we did.”

But Reynolds was the centerpiece.

“Donny was a great guy to have on the team,” Solberg says. “I really enjoyed coaching him, but even more, I enjoyed watching him run. He was a good one, wasn’t he?”

Solberg coached some great running backs at Corvallis, among them son Jimmy Solberg, Robb Thomas and Jay Locey. Were any of them as good as Reynolds?

“I don’t think so,” the senior Solberg says. “Jimmy was pretty good, but he didn’t break away for a touchdown for every game in the playoffs the way Donny did. He was so quick. He says he just didn’t want to get tackled.”

Solberg laughs at his last line, but there is some truth to it.

“Donny didn’t want to get tackled, and nobody could tackle him,” says Norv Turner, the starting quarterback during Reynolds’ senior season at Oregon. “That is the calling card of the great runners. They find a way to compete through all situations.”

“It seemed like Don never got hit hard,” Dave Roberts says. “He never got knocked backward. (Defenders) would just get a piece of him and he was always falling forward. He had that exceptional quickness and juking ability. That’s what always impressed me. He had a lot of heart. When he did get hit hard, he bounced up and kept coming back.”

“He made so many guys miss (tackles) between the hashmarks,” Beck says. “He wasn’t a big-time sprinter, but his ability to keep his pace and go upfield and make you miss was a wonderful quality. Plus he could catch the ball, and he was a good blocker for us. In the high school setting, he was faster and quicker than the guys he was playing against.”

Reynolds worked most closely with Riley in the Corvallis offense. The option was their bread-and-butter play.

“There were so many times when we would be moving down the field, Mike with the ball, me beside him and just one defensive back out there,” Donny says. “Sometimes the whistle would blow (inadvertently) because he faked so well. He handled the ball magically, and his timing on the pitch play … I don’t know how he did it. Mike was tremendous. I don’t think I ever dropped a pitch, because he always laid it in perfectly.

“That combination of his ball control, the system we ran with the fullback and the options were perfect. And the linemen in front of us were tremendous. They were not just good, but great.”

Riley says Reynolds “had it all” as a prep halfback.

“He was powerful, quick, instinctive with great vision — the perfect running back, really,” Riley says. “If we had thrown the ball, he would have been a great receiver. His change of direction and his instincts were incredible, and he had a low center of gravity. He was really hard to tackle.

“As a teammate, Donny was among the very best, and we had plenty of good ones. We were a bunch of guys who played together for years prior to getting to high school. It turned into a culture of it being about the team and about getting to play together. Donny was an example of a guy who played multiple sports and was a leader of those teams.”

Riley add this: “I would put him up against any high school running back in the history of the state of Oregon, right in there with Woody Green and Thomas Tyner. He was so good, and he did what he did in an offense centered on the fullback.”

Hackenbruck credits Reynolds’ ambition and, well, gumption.

“Donny had some innate skills, but he also was driven,” Hackenbruck says. “He played with a passion no matter what sport he was playing. He was always one of the better players, but stuck out because of his drive. Part of that might have been being one of the few black kids in town.

“He was a great guy to be around. He never treated people poorly. He was never conceited, never caught up in himself. He was amongst some good kids. We were lucky to live in Corvallis, a place where a kid could grow up slowly and wasn’t thrown to the wolves at a young age. That helped make him a better person.”

After leading Corvallis to the state baseball championship in 1971, Reynolds finished his prep football career as a member of the North team in the annual Shrine All-Star Game in Portland. Reynolds spent two weeks in training camp with fellow Spartans Riley, Beck and Hackenbruck as well as Spiegelberg, Fouquette and Krpalek.

“We practiced twice a day, but there was a lot of down time and a chance to get to know one another,” Spiegelberg says. “I have gotten to know Donny better through the years and found that he is an exemplary human being. Funny. Great sense of humor. Not afraid to dish it out, all in good spirit.”

“I played with Donny in the State-Metro baseball game, too,” Fouquette says. “He was a terrific teammate. To excel in two sports in college? It shows you what kind of athlete he was, and he is maybe a better person. Everybody loves him. He is one of those guys who everybody likes to be around.”

During Shrine camp, Reynolds and Beck were also playing in the American Legion state playoffs against Madison.

“We would practice football, and then go play baseball, or sometimes vice versa,” Reynolds says. “It was hectic. But playing in the Shrine Game was special. it was fun being around all those guys and getting to know people who had been on the other side of the line from us.”

► ◄

The Reynolds boys as young men -- in front, Ron and Donny; in back from left, Harold, Larry and Tim (courtesy Reynolds family)

Just for fun, I asked the Reynolds brothers who was the best athlete among them. Their answers were interesting, and not surprising. Nobody picked himself.

HAROLD: “Larry, In every sport. We used to think he was Freddie Boyd in basketball. He was the Pac-8 Freshman of the Year in baseball. In football, he started four years at cornerback. He used to say he defended James Lofton and Tony Hill in practice all week, so Saturdays were a day off.”

LARRY: “That is a tough one to answer. The best collegiate athlete was Don. The best pro athlete was Harold. Don starred in both baseball and football at the collegiate level, so if I have to pick one, I would say him. He was special.”

DONNY: “It would be Harold. Larry was a better athlete than I was, too. It trickled down. All my brothers were athletic, but Harold got the mother lode of athleticism.”

► ◄

Donny’s initial decision was to play only baseball in college, and he signed a letter of intent with Oregon. That came after a recommendation from Dave Roberts, who was the No. 1 pick in the 1972 MLB draft and would go on to a 10-year career in the big leagues.

“I talked to (Oregon baseball coach) Mel Krause about Don,” says Roberts, who wound up playing baseball with Reynolds for a season apiece at the high school, college and MLB levels. “Mel wasn’t recruiting him. The basketball program was recruiting Dean (Roberts, Dave’s younger brother), but the football and baseball programs were not recruiting Don.

“I told Mel, ‘You have to watch Don Reynolds play. He can help us right away.’ And I told Don as he was trying to make a decision about where to go to school, ‘You will start at Oregon as a freshman.’ I think that may have pushed him over the hump in his decision.”

Reynolds had a scholarship offer to play football at Oregon State. He was close with head coach Dee Andros and with assistant Bud Riley, Mike’s father.

“I couldn’t have been treated any better than I was by Dee Andros’ staff,” Reynolds told me last week. “That made it such a painful decision. I had to tell to Bud I was going to Oregon. Just thinking about it, I am almost tearful right now, because Bud was so instrumental in my life. I don’t think people realize how difficult that decision was for me.”

In my 2014 book, “Civil War Rivalry — Oregon vs. Oregon State Football,” Reynolds explained his decision.

“The Beavers recruited me as hard as anybody,” Donny said. “Dee picked me up at school several times my senior year. I rode in that orange and black Oldsmobile 88 (known as the “Pumpkinmobile”) that he drove. Bud Riley was my contact, and you know how I felt about the Riley family. But Gene Tanselli was Oregon State’s baseball coach, and he never said a word to me. Not a word. I’d come up and he’d instantly stop talking, turn around and walk away. I think he was a racist. If he’d have even said, ‘I’ll give you a chance to make our team,’ I’d have gone to Oregon State. I would have been a Beaver.

“I liked Dee a lot. Their offense was the same offense we ran in high school. It would have been hard to walk away from that whole group there. I felt very welcomed being around those guys in the football program. All the people were great at Oregon State, with one exception.”

At least Donny was only 40 miles down the highway while attending Oregon.

“One of the reasons he went to Oregon and not Arizona State (to play baseball) was so he could make sure (his brothers) were in school, and if something was going on, he could drive back home and see us,” Harold says. “I spent almost every weekend of his college career in Eugene with him. He made sure I was on the straight and narrow, staying out of trouble and that I was doing the things I needed to do.”

Reynolds had a surprise waiting for him during the summer of ’71. After the Shrine football game in August, Oregon football coach Jerry Frei visited him in the locker room.

“I would consider it an honor if you would play for our freshman team,” Frei told Reynolds.

“That shocked me,” Donny says. “Then Mel told me, ‘If you don’t play this year, you’ll be making a mistake.’ He talked me into going out for football.”

Reynolds played at 5-8 and 170 in high school, but he was thicker than Larry and Harold, who were slender.

“God built him different than Harold and me,” Larry says. “He is short and stocky and had to take more bullets (as a ballcarrier) than we did.”

Donny led Oregon in rushing for three straight seasons from 1972-74 (courtesy Reynolds family)

Donny weighed about 180 by his senior year at Oregon, but he was still on the smallish side. He was an immediate success, starting for the Frosh team in 1971, then leading the Ducks in rushing for all three varsity seasons.

It wasn’t a period of success for Oregon football, however. Reynolds served under three head coaches. Frei recruited him. He played for Dick Enright as a sophomore and junior and for Don Read as a senior. The Ducks were a collective 8-25 over those three seasons.

Donny began his sophomore year as fourth-string tailback, but worked his way up quickly. After busting a 32-yard TD run at slotback in a loss to Washington State at midseason, he became the starter at tailback.

The next game, he broke off an 85-yard touchdown run — the longest of his career — that was critical in a 15-13 upset of 13th-ranked Stanford. It came on an option play with senior quarterback Dan Fouts.

“Dan pitched it and got smoked,” Reynolds says. “I caught in on the left sideline and made a hard right cut. I felt like I was surfing through a wave of defenders. I’m not a surfer, but it was my impression of being in the curl.”

Reynolds capped his sophomore season by breaking the first play from scrimmage 60 yards for a touchdown in a 30-3 Civil War rout at Parker Stadium, snapping Oregon State’s eight-year stronghold in the Civil War rivalry. Does Dan Fouts remember the play?

“Do I ever,” Fouts told me from his home in Sisters. “Game over. The play call was some type of option; giving the ball to Donny was a good option. I can see it today. The hole opened so wide, it seemed like there was nobody there. It was a beautiful thing to see.”

The play call was actually a straight counter. In “Civil War Rivalry,” Reynolds recounted it this way:

“We were just going to hand off and establish the running game. My goal was to get to the hole as quick as I could before they could move. I hit it hard, something popped and I was in the clear. I was as shocked as anybody.

“I was happy to score for Oregon, but I’m looking into the stands at people I know. I wasn’t euphoric like you might think. This is my home field and I have people rooting against me, yelling at me as I walk on and off the field before and after the game and at halftime. That’s not the way it should be.”

Ironically, Larry missed the excitement. He was late for the game and walking into Parker Stadium when he heard the public-address announcer say, “That’s 60 yards by Donny Reynolds for the touchdown.”

“I missed the stinking run,” Larry says with a laugh.

It wasn’t until Larry got to Stanford that he realized how good a football player his older brother was.

“I played with Darrin Nelson and against some of the great backs, including (USC’s) Ricky Bell,” Larry says. “Looking back, I think Don was in the same category.”

Donny finished his sophomore year with a team-high 421 yards on only 52 carries (8.1 average) and four touchdowns, and also caught 11 passes for 70 yards.

“The first thing that comes to mind about Donny was his toughness,” says Fouts, 74, who was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame after a 15-year career with the Chargers. “Second was his smarts. Third was his personality. He was a hard-nosed running back who never made mistakes and always seemed on top of things. He was upbeat and a class teammate — a first-class guy.”

Reynolds had his best individual season as a junior, earning All-Pac-8 honors. He ranked fourth in the league with 1,002 yards and six TDs rushing in 11 games and also had 13 receptions for 94 yards and a score.

Donny was an All-Pac-8 halfback as a junior in 1973 (courtesy Reynolds family)

As a senior, Donny was third in the league (behind USC’s Anthony Davis and Cal’s Chuck Muncie) with 787 yards rushing in 11 games, plus 19 receptions for 140 yards. Reynolds had the biggest game of his career in a 14-10 loss to Northwestern, rushing 23 times for 196 yards.

The starting quarterback during Donny’s senior season was Turner, who became more well-known as a coach. Turner coached 45 years, including nine seasons at USC under John Robinson, the final one as offensive coordinator. Turner would go on to coach 34 NFL campaigns — 15 as a head coach and another 13 as an offensive coordinator.

“Donny was a heck of a player, a very intelligent player,” says Turner, 73, who retired from coaching in 2019 and lives in Del Mar, Calif. “He had great running back skills, a lot like some of the backs I coached through the years (in the NFL). He had great balance and change of direction, and being short, was very hard to find and hard to tackle. Defenders had trouble finding him.”

Turner believes Reynolds could have had a career in the NFL.

“He was smart to go the route he did (in baseball), but he could have made it in the NFL, too,” Turner says. “To play running back, you have to be such a great competitor. That is where it started with Donny. Plus, he was a good receiver.

“We didn’t win a lot of games at Oregon, but I take pride in being part of that group and how much we cared for each other. And Donny was one of the leaders of that team. We had a lot of fun together. He is one of the favorite teammates I ever had.”

Riley, too, figures that Reynolds could have played in the NFL.

“He would have been like Quizz (Jacquizz Rodgers), the same kind of player,” Riley says. “He could have played first down or third down in the NFL, because he was a capable receiver.”

Reynolds wasn’t selected in the NFL draft.

“It was a disappointment,” he says. “With my collegiate career, I should have gotten an opportunity. Maybe I wasn’t big or fast enough for them, but the numbers I put up in college warranted at least a look-see.”

► ◄

Reynolds’ baseball career at Oregon got off to an inauspicious start. As a freshman, he was left off the roster for the spring trip to California.

“I was a scholarship baseball player, and that infuriated me,” Donny says today. “I was looking to transfer. Arizona State had recruited me, and if they told me I could come right in and play, I would have transferred. I was very upset with Mel Krause. To this day I am. I was disillusioned.”

Things got better quickly. Donny broke into the starting lineup early in the season and stayed there for four seasons, mostly as a left-fielder. His best individual season was as a sophomore, when he hit .358 with eight homers with, 33 runs and 30 RBIs, a .485 on-base percentage and 11 stolen bases in 35 games.

Reynolds was a three-time All-Northern Division selection and ended his career with a .315 batting average and seven school career records, including hits, RBIs and stolen bases. He still ranks second on the Ducks’ career list with 40 stolen bases and sixth with 111 runs scored.

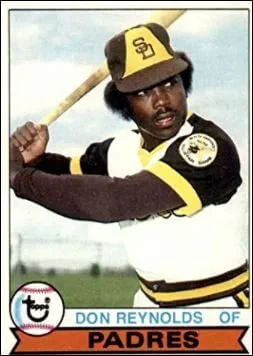

After his senior year, Donny was selected in the 18th round of the MLB draft by the Padres.

“That was a real disappointment,” he says. “I got calls from (representatives of) several teams saying, ‘We are going to take you.’ I thought I would go in the top 10 rounds. A lot of clubs said there were concerns that I was going to play (pro) football.”

The Southern California Sun of the World Football League was interested — “I spoke with them,” he says — but nothing came of it.

Reynolds climbed the Padres’ farm chain quickly. In 1975, he hit .319 with 15 homers and 61 RBIs in 78 games for Walla Walla of the Class-A Northwest League. In 1976, he batted .333 with 19 homers, 94 runs and 85 RBIs in 125 games for Amarillo in the Double-A Texas League. He was hitting .368 with a .467 OBP in 42 games with Triple-A Hawaii in 1977 when he broke a leg, ending his season.

“At that time, I had as much confidence and was hitting the ball as well as I ever did in my career,” Donny says. “I was very locked in.”

Reynolds made the Padres in 1978 and stayed with the big club the entire season, but got only 102 plate appearances in 57 games, hitting .253. He split the 1979 season between San Diego and Hawaii, batting .222 in 53 plate appearances and 30 games for the Padres.

Reynolds played two seasons with the San Diego Padres in the late ‘70s

During his time with San Diego, Donny played with four future Hall of Famers — Ozzie Smith, Dave Winfield, Gaylord Perry and Rollie Fingers — along with Randy Jones, Gene Tenace and Mickey Lolich.

“I roomed with Ozzie on the road for awhile my first year,” Reynolds says.

The ’79 campaign was the end of his major league career. He spent the entire 1980 season with Hawaii, hitting .290 with nine homers, 63 runs and 50 RBIs in 113 games. The Padres released him after the season and he signed with the Mariners, who optioned him to Triple-A Spokane. After hitting .283 in 68 games for the Indians, his pro career was over at age 28, with a six-year minor league batting average of .311.

“So many teams needed bats, I thought I had shown enough to get a look somewhere,” Donny says. “It just didn’t happen.”

Reynolds feels that he didn’t get a fair shake with the Padres.

“When you are used to playing every day, and (with San Diego) you are sitting for five, to six days a row and don’t see a pitch, it is hard to keep sharp,” Donny says. “For me to stay in a rhythm I needed to be playing consistently — even every other day. There were a lot of long stretches where I just sat there. I got rusty.”

Dave Roberts, who played with the ’78 Padres, agrees that Reynolds wasn’t given a real chance to show what he could do.

“You could see the potential in him — as a hitter, especially,” Roberts says. “Don had the same swing in high school as he did when we played together in San Diego. It was a short, compact, powerful swing. He sprayed line drives all over the ballpark. It didn’t seem to me like his swing ever changed. He was gifted, plus he worked hard at it. He was a really good hitter.

“But he didn’t get very much of a chance to play in the big leagues. They expect a left-fielder to hit, and hit for power, too. Don had some power, but not a lot. I could have seen him hitting from .280 to .300 with 15 home runs (a season). He dominated in Triple-A. He could have hit in the big leagues and been very successful. He just didn’t get the opportunity — never on a regular basis. It was like, if you get a hit today, you might play tomorrow, or you might not play for two weeks.”

► ◄

With a degree in psychology at Oregon, Reynolds served two seasons as an assistant to baseball coach Jack Riley at Oregon State, gaining a Masters degree in guidance and counseling.

“I thought when I was done with my playing career, I would be one of those guys who helped high school kids figure things out,” Donny says.

But the Mariners offered him a position as a roving instructor, and one of his many jobs was to work with a young Ken Griffey Jr. when he was with San Bernardino in the minors in 1988.

“They wanted me to monitor his progress and be a guiding light,” Reynolds says. “We established a very good relationship. To this day, we have a special bond.”

Over the next three decades, Reynolds worked as a scout for the Astros, Rockies, Rangers, Braves and Diamondbacks. He also served three seasons as director of player development for the Montreal Expos. In Houston, he headed up a sports psychology program for minor leaguers. Reynolds figures he put in nearly 20 years as a scout.

In recent years, Reynolds has focused on doing individual player development evaluations along with working youth camps and clinics, mostly in the Northwest.

“So many young people are being told things that don’t help them get to where they need to go,” Donny says. “You have to help them understand who they are, what their skill set is, and the work ethic they have to create to move forward. We focused on teaching them basic fundamentals, and that those things need to be consistent. The main thing is for them to understand they are important in their own development. You can’t sit there and wait for somebody to tell you what to do. You have to work at it.

“The enjoyment I got was from watching kids get better and giving them information that might help them navigate the recruiting and pro scouting stuff. It was also about talking to parents about taking it easy, and to not get overwhelmed by so much of the stuff that is out there.”

► ◄

Donny Reynolds (second from left) with, from left, son Isaac, wife Jan and daughter Simone

Donny and Jan moved from Portland to Arch Cape — a few miles from Cannon Beach — as a permanent residence in 2019.

“It’s quiet,” he says. “It’s peaceful. I can fish. It is a little isolated, but I like it.”

He regularly goes ocean fishing with a group that goes out on a charter boat.

“We catch bottom fish, and sometimes salmon hit,” Reynolds says. “We get a lot of crab. I am going to start fishing the rivers again. I have been a river fisherman since Dean Roberts taught me a long time ago.”

Donny has had a pair of recent replacement surgeries, to a hip in 2024 and a knee earlier this year. He has lost a considerable amount of weight and wants to get down even more.

“I am working on it,” he says. “I am moving around and feeling pretty good, but it is easy to get lethargic as we get older. I have to address that.”

Reynolds keeps in regular touch with friends such as Riley, Beck and the Roberts brothers. And of course, with his own brothers.

“Don loves people,” Larry says. “He is very outgoing and gregarious. There is a lot of personality in there.”

“He is one of my best friends in the world,” Dave Roberts says. “There is no finer Christian man than Don Reynolds.”

“Donny is one of the most loyal friends you could ever have,” Riley says. “The friendship we made in high school has endured a lifetime. His consistency is phenomenal. He feels like the same guy I knew in junior high.”

If Reynolds has a best friend, it might be Beck.

“I am sure a number of guys would say he is their best friend,” Beck says. “They would all claim that. He appreciates the friends he has and he never acts like he is above you in any way. He is just Donny.

“More than 60 years after we first met, we are still good friends. That’s special.”

In 1993, Reynolds was inducted into the U of O Sports Hall of Fame. Now, more than 30 years later, his number has been retired at Corvallis High.

He heard the cheers again Friday night. They meant a lot.

Donny addresses the crowd at Corvallis High after the presentation

“That honor is really for all of the guys who played with me,” Donny says in a moment of reflection a day after the retirement ceremony. “Really, the entire class of ’71 was a special group. I can’t stress enough how much that had an impact on my life, having teammates and friends like that. We competed and had a lot of fun. Our class felt like a family.”

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.