The bill that set up the bill to build a ballpark in Portland

HOK’s drawing of the proposed ballpark in Northwest Portland in 2001 (courtesy John Vozmek)

Updated 5/30/2025 11:20 AM, 4:35 PM

The Portland Diamond Project has been the driving force behind Oregon Senate Bill 110, which passed through the Senate in April and is now being considered by the House of Representatives. The bill would clear the way to access state bonds of up to $800 million for construction of a baseball stadium on Portland’s South Waterfront. Insiders say they expect a vote in the House within a couple of weeks.

The 2025 bill actually updates Senate Bill 5 of 2003, which directed $150 million in players’ income taxes toward funding a new stadium in Portland.

Why did the original bill that was placed before the Oregon Legislature in 2001 fail? What was the group that spearheaded that attempt to lure Major League Baseball in 2003? What were the circumstances that led to the bill’s passage that year? And why did MLB bypass the City of Roses for the franchise to replace the Montreal Expos?

I spoke to most of the key figures from that time 22 years ago. I will let them tell the story.

► ◄

Steve Kanter

In 2000, Steve Kanter became president of the Portland Baseball Group, setting it up as a 501(c)(4) and (3) non-profit organization with the goal of bringing Major League Baseball to Portland. Kanter, now 78, grew up in Cincinnati as a Reds fan, graduated from MIT in 1968 and from Yale Law School in 1971. One of his good friends at Yale was Larry Lucchino, who would become president of the Orioles, Padres and Red Sox. Boston won World Series three times under his watch.

Kanter moved to Portland shortly after he graduated from Yale Law School. Beginning in 1976, he taught constitutional and criminal law at Lewis & Clark Law School and served as dean there from 1986-94. He took a year’s sabbatical to Greece in 1994, the year of the MLB strike that wiped away the last month and a half of the regular season, cancelled the World Series and, adds Kanter, “killed the Expos.”

Before the strike was settled in April 1995, he cold-called acting MLB commissioner Bud Selig. Shockingly, Selig returned the call, “and we had a long talk,” says Kanter, now 78. “He was an extremely candid, nice guy who loved baseball.”

Why would Selig return the call from a stranger in Portland?

“Our official name was Northwestern School of Law of Lewis & Clark College, and that is how I identified myself (in his voice message),” Kanter says. “One of Bud’s closest friends and primary lawyer was Bob Dupuy, who had studied at Northwestern Law School in Chicago. I have always suspected Bud was mistaken about which Northwestern I was at.”

Selig — who owned the Milwaukee Brewers — was looking for a full-time commissioner. Kanter believes that after a couple of conversations with Selig, “I became a really long-shot candidate to become commissioner.”

“That is how I figured out the Expos were dead and needed to move, somewhat earlier than most people knew,” Kanter says. “I met a lot of (MLB) owners and shared my ideas about what I thought needed to happen with Major League Baseball. And I discovered a clearer picture of their financial situation.”

► ◄

Lynn Lashbrook

In 1996, Lynn Lashbrook moved from St. Louis to Portland. A year later, he started his company, Sports Management Worldwide. Lashbrook had been athletic director at Alaska-Fairbanks from 1988-93. During that time, he met a Portland architect named John Vosmek. Lashbrook contracted Vosmek for some work.

John Vosmek

“I did a master plan for their athletic facility and designed a student-recreation center that got built — no small task,” Vosmek says.

During the mid-1990s, there were plans for renovation of aging Civic Stadium (now Providence Park). The PCL Portland Beavers had left town in 1993, and there was a movement to get Triple-A baseball back.

“Athletic facilities were a specialty of mine,” says Vosmek, now 85 and in the process of finally retiring after a long career. At one point, he started working with a local engineer.

“As we got into it, we started thinking, ‘Couldn’t we expand it to Major League Baseball capacity, just in case?’ ” Vosmek says. “We came up with a scheme for that, shopped it around a little.”

“The bill was a bit of genius, really,”

After Lashbrook moved to Portland, he connected with Vosmek. Lashbrook, 76, had grown up a Kansas City Athletics fan and, as an adult, followed the Royals. When he learned the Portland metropolitan area had substantially more people than Kansas City, “I got passionate very quickly about bringing a major league team to Portland.”

That wasn’t going to be at Civic Stadium, soon to be PGE Park, though it could have been an interim site as a new stadium was being constructed. By 2010, it would become a soccer-only facility. But there were other sites in Portland on which a new MLB stadium could sit.

Lashbrook organized a small group of supporters of the idea, which became a sort of ad hoc committee. Lynn arranged for a full-page ad in The Oregonian. Al Moffatt, a local advertising executive, created some TV spots. A logo was developed. A campaign was on.

Bumper sticker paid for by Harvey Platt of the Portland Baseball Group (courtesy Steve Kanter)

Lashbrook and Vosmek had a meeting with Portland mayor Vera Katz, who was intrigued by the idea and became a supporter of building a stadium to lure Major League Baseball to Portland.

“She set up a meeting with Phil Knight,” Vosmek recalls. “After the meeting, he said he expected Vera to call him back. His parting words were, ‘I guess I will hear from Vera now.’ My understanding is she never followed through with that.”

The original idea was to retrofit an MLB ballpark into Civic Stadium. Vosmek was paid $20,000 to build a scale model of a renovated Civic. Vosmek got the money from Chuck Richards, the owner of Sunset Athletic Club. Richards was also director of the Oregon Sports Academy, which ran a bingo program that raised thousands of dollars for amateur athletes and club sports in the state of Oregon.

Chuck Richards

“Lynn was a fire-breathing dragon,” says Richards, 80 and long-time president of the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame. “I liked his enthusiasm and wanted to help. I was Lynn’s wing man. We donated $20,000, had the model built. People could see three-dimensionally what the park would look like.”

“Lynn had enormous energy,” Kanter says. “He wanted baseball, and he brought a lot of important people in to meet with us. Some of them were not what we needed; some of them were excellent.”

One of the “excellent” ones was Randy Vataha, the former NFL receiver who was living in Boston and was co-founder and co-owner of Game Plan LLC, a company specializing in the buying and selling of pro sports teams.

“I knew we needed an outside consultant,” Lashbrook says. Vataha was hired for an initial investment of $20,000. “He gave our group instant credibility.”

To pay Vataha’s fee, Lashbrook sought contributors.

“Lynn introduced me to Craig Byrd and also to Harvey Platt,” Kanter says. “Both of those guys became supporters who helped us out financially. Harvey bailed us out a number of times.”

Craig Byrd

Harvey Platt

Drew Mahalic, CEO of the Oregon Sports Authority from 1996-2018, told Lashbrook his organization would match the first $5,000. Byrd, whose Byrd Financial Group was housed in the same building as Mahalic’s, donated $5,000. When Lashbrook had trouble raising the final $10,000, Byrd wrote another check for that amount.

Drew Mahalic

“My boys played college baseball,” says Byrd, 77, who wound up contributing $50,000 for Vataha’s work over a two-year period. “I am a baseball guy. I wanted to help get the campaign going. We went to a lot of meetings to raise more money to help. A lot of other people put some money in.”

Meyer Freeman was helpful through those times. He started as an intern with Lashbrook’s Sports Management Worldwide for two summers and then was hired by the Oregon Sports Authority in 1999, eventually becoming COO.

Meyer Freeman

“I helped Lynn and Drew figure things out and tried to make it a more collaborative environment,” says Freeman, now 46, living in Astoria and working as lead advisor at the Clatsop Community College Small Business Development Center. “I was a bridge between the Portland Baseball Group and the Sports Authority early in the process (of developing a stadium bill). Initially, I thought, ‘This thing doesn’t have a chance, but it could be a great experience to be part of it.’ And I enjoyed working with Lynn and Drew.”

The hiring of Vataha piqued Kanter’s interest.

“The key that got me heavily involved is we got Randy,” Kanter says. “We needed somebody with clout. He is a super smart guy. He was perfect for Portland. He delivered more than he promised. He was not a showman. He was a really solid guy to work with. Once we got Randy on board, we were able to get things done. His company was well-regarded. We brought him out regularly and helped us put together the book that we used to pitch people. I could tell from the beginning Randy was the kind of person I would be willing to work with.”

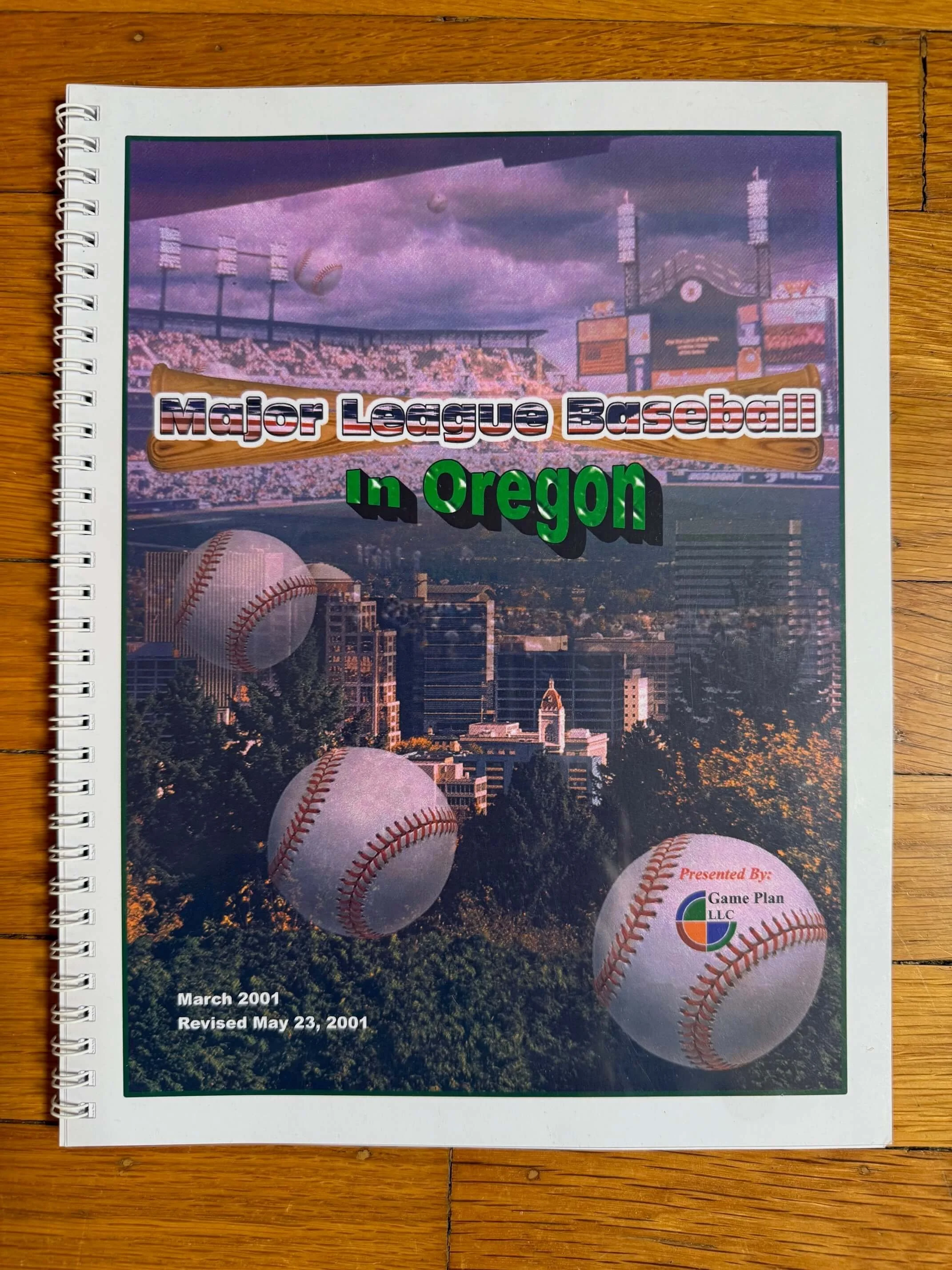

Kanter flew to Boston to meet with Vataha, who did the analysis and eventually wrote a 70-page book, making the case that was both persuasive with MLB and was the core of the Portland Baseball Group’s case with the Oregon legislature.

The “book” put together by consultant Randy Vataha in 2001 to help promote the Portland Baseball Group’s proposed stadium bill (courtesy Steve Kanter)

“Randy was critical in 2001,” Kanter says. “The real effort to get the Expos started in that year.”

And it was almost a home run.

“It should have happened (in ’01),” Kanter says. “It was so close. Everything was lined up. And then it wasn’t.”

► ◄

The Expos were in financial trouble in Montreal. After the strike, ownership began unloading some of their best players, including Larry Walker and Cy Young Award winner Pedro Martinez. Majority ownership was transferred to Jeffrey Loria, who was unable to turn the team’s fortunes. By 2001, the Expos were in the midst of their fourth straight 90-loss campaign. Attendance plummeted, Olympic Stadium was in disrepair and business support for a failing team was dying.

“The thing we had going for us was the Expos were still owned by Loria,” Kanter says. “He was bleeding money. He needed to move the franchise. No way they could keep functioning in Montreal. They were getting their revenue in Canadian dollars and paying in U.S. dollars, which was a 30-percent deficit. He was desperate.”

As the calendar turned to 2001, Kanter and his cohorts with Portland Baseball Group kicked into gear.

There was little time to waste. The Legislative session started in January and would be done by early July. PBG had many tasks, including recruiting key people to the cause, incorporating, raising funding, working with city officials, cultivating MLB, working with Vataha and reaching out to the Expos.

“We knew we had a unique opportunity,” Kanter says. “Major League Baseball rarely moves a team, and the Expos were going to have to move. The Legislature met only every two years. We thought that waiting for 2003 might be too late. It would be a six-month project. We would either get the Legislature behind us, or we wouldn’t. Oregon had a history of being lacking in getting big things done. Maybe we could do it.

“We had a group of well-meaning people. We didn’t have a lot of experience, or the financial resources to own an MLB team, but we did have some savvy.”

Vataha increased the savviness. He had co-founded Game Plan in 1994, a company that would represent buyers of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Golden State Warriors in the 2000s. Beginning in 2001, he spent two years consulting with the Portland Baseball Group.

“It was a great community effort,” says Vataha, 76 and now the company’s chairman, with son Collin serving as president. “I spent a lot of time with Steve and John. Steve was steady, never got upset and stuck with what he knew was the right way to do it. They did a good job getting the political support and educating the legislators and the public that the amount of funding that would go toward the baseball park would be offset by the additional income tax revenue from players.

“We told them from the beginning, the tough part is always Major League Baseball. They are the one wild card to getting a deal done. We had a couple of teams we got to the finish line that it didn’t end up happening for.”

Vataha gathered information on player salaries, how the MLB’s collective bargaining agreement worked, how stadium transactions started and were completed.

“You have to understand all the components so you are not fooling yourselves,” Vataha says. “We made sure they knew all the things they had to understand about acquiring a team.”

The Baseball Group leaders did not have a prospective majority owner in place.

“We had good support across the state, although we did not have a lot of money,” Kanter says. “Some of our folks would have been minority owners, but we didn’t have the ‘whale.’ ”

A “whale,” in pro baseball vernacular, is an owner with plenty of dough.

“At one point, Loria was going to keep ownership, move the team here and acquire minor local owners,” Kanter says. “Once the team was performing, he would sell off the rest of it.”

Vataha would have helped with that.

“The owner was always the challenging thing,” Freeman says. “Vataha said, ‘If the financing for the stadium is there and a team is available, an owner will be there. When the time is right, we will bring an owner to the table.’ ”

“Had the timing worked, Major League Baseball would have asked, ‘Who is going to be the controlling owner?’ ” Vataha says. “We had some people interested, and I know (Portland Baseball Group) had some potential candidates, too.

“It is not just about raising the money. (MLB officials) want to know who has the power. There are no committees in (MLB team) ownership. One guy makes the decisions. It has to be clear there is one controlling owner. In most cases, that is the one who puts in the most money. (MLB wants) to know either the controlling owner has the money to build the ballpark and buy the team, or there is a genuine means for funding the stadium.”

Once the funding was in place for $150 million in 2003, “that would have been an attractive deal for an owner, to get that much funding for the ballpark,” Vataha says. “He could put most of his money into buying the team.”

► ◄

As Kanter stepped forward as the leader of the Portland Baseball Group, Lashbrook stepped back.

“I was the crazy guy who stirred things up,” says Lashbrook, who is still running SMWW. “I laid back, but I was still a spirit in the group. I was still involved, but I was doing my business; my priority was my company.”

Kanter was beginning to believe getting a stadium bill passed was a possibility. Portland was the largest market in the country with only one of the Big Four pro sports.

“We were the only show in town,” Kanter says. “We had an interim facility (Civic Stadium) while we were building the ballpark. The hardest piece of the puzzle would be getting the rural-dominated legislature to support something that would ultimately be in Portland. If we could get them to buy in, the rest would be easier. If we could put all the pieces together … but we were under the gun time-wise.”

PBG hired lobbyists to take their case to the legislature. Kevin Campbell took the lead with major support from Dave Barrows and Alan Tressider.

Kevin Campbell

“They were an excellent team,” Kanter says.

The biggest obstacle would be getting House Bill 2941 passed through the Legislature. It called for $250 million in revenue bonds, with $150 million for the stadium project and $100 million going to K-through-12 education.

“The $150 million would have paid for about half (actually 40 percent) of an MLB park at that time,” Mahalic says.

“Today, that might cover one year’s salary for (Shohei) Ohtani,” Platt quips. (Actually, two years).

There was opposition to the bill. Oregon was in a recession, and many legislators thought it foolish to pass a baseball stadium bill when the state had so many other financial needs.

“In the beginning, we were trying to get some traction with both MLB and legislators,” Kanter says. “The first draft of the bill started in the House, and we were admitting to the House members, ‘This is not going to be the final version.’ We were still looking for the best possible mechanism but needed to get something moving in the Legislature. If you don’t get something going by a certain stage, you don’t have any chance. So they started out with a bill that was not perfect, but it was enough to start the process.”

Several people involved with the campaign were trying to come up with the definitive financing plan.

“It was kind of a group effort,” Kanter says.

Senator Ryan Deckert, a major proponent of the bill, met with a group that included Dr. Paul Warner, the state’s legislative revenue officer.

Ryan Deckert

“Paul was great — the Ph. D economist,” Deckert says. “That is where we came up with the idea of using player income tax revenue. Oregon was a high income-tax state.”

The plan would be to tax not only players and upper management from the Portland team, but also those from the visiting teams for the days they spent in the state playing baseball.

“I remember the room,” Deckert says. “It wasn’t just me. We had a small group. We started playing with the idea. I called Tom Brian, the previous Washington County commissioner, who knew revenue. He said, ‘This could be a great mechanism.’ And Paul gave us the ‘Yes, you can do this.’ It put us in the game when we came up with that.”

Campbell met with state Treasurer Randall Edwards and “his experts on bonding.”

“While Legislative Counsel had to draft the language, I remember Treasury providing the subject-matter experts,” Campbell says. The plan was likely unprecedented to finance a stadium.

“I am not aware of any other bills using the concept of sequestering taxes specific to players as a part of funding a stadium,” Campbell says. “It only works in a state with a high- or meaningful-income tax. There are very few situations where sequestration would work, so it really was an elegant solution.”

Eureka! A workable plan.

“The bill was a bit of genius, really,” Vosmek says.

“I would give most of the credit for the (player income tax) idea to Randall, Kevin and his folks and ultimately to Ryan Deckert’s group,” Kanter says. “They were very knowledgeable and creative.”

“The income tax plan works perfectly,” Campbell says. “It involves, among others, players from the Yankees or other high-network teams with high payrolls. They pay the tax when they play in the state. If it was just an Oregon team, you wouldn’t see as much value. But when you start adding every team that would play here, it is a pretty good chunk of money.”

House Bill 2941 passed through the House 31-27. The bill then moved to the Senate, where Lenn Hannon, who represented rural Jackson County and was co-chair of the Joint Ways and Means Committee, was against it.

“Lenn was death on the baseball bill from Day One,” Kanter says. “Before we had a chance to talk to him, he said publicly, ‘I am not voting for anything for baseball for Portland.’ I spent the entire Legislative session trying to talk to him. He dodged me. Finally I ran into him on the floor at the Capitol and I said, 'Lenn, I would love to have a chance to talk to you.' He said, 'That would be fine.' I asked when. He said, 'The day after the legislative session adjourns.’ ”

Two weeks before the end of the session, Kanter, Kevin Campbell and his father Larry — also a lobbyist — met with Governor John Kitzhaber and Senate president Gene Derfler. Derfler was against the bill, but said if they could get Kitzhaber to support it, he would let it go to a final “up or down” vote on the floor.

“We worked like crazy through Bill Wyatt (the governor’s chief of staff) to persuade Kitzhaber, and we finally got his full-throated support,” Kanter recalls. “We had 20 of the 30 senators committed that they would support SB 978, the refined Senate version of the baseball bill.”

Kanter had been in communication with Selig throughout the effort that had begun six months earlier. The interim commissioner said if the bill passed and $150 million were dedicated to a stadium build, he would announce Portland as a viable candidate for relocation of the Expos.

In the final Republican caucus the night before the Legislature adjourned, Derfler told the members that he was going to let the baseball bill go to the floor for a vote. At that point, Hannon stood and declared, “I have told you that the bill would pass only over my dead body. If you let it go to the floor, we will be starting over on the state’s overall budget. Maybe we will be done by December.”

Says Kanter: “At that point, Derfler folded.” SB 978 never made it to the floor.

“Hannon refused to allow the bill to have a hearing,” Campbell says. “Then he read what he called ‘a baseball obituary’ on the Senate floor.”

“The only thing I regret during the whole process is I had told the commissioner’s office the day before, ‘We are going to get our vote tonight,’ ” Kanter says. “I said, ‘Not many people in Oregon know how close we are. We are going to need some backup from you guys tomorrow once we get this legislation through.’ The commissioner was going to make a statement. I had to call him Saturday morning to say we didn’t get our vote.”

It turned out to be a valiant test run. Things would turn out differently two years later.

Says Deckert: “In 2001, we didn’t have the creativity we found in 2003 that finally unlocked the puzzle.”

► ◄

With the Expos in desperate financial shape — they were losing $30 million a year — there was talk of contraction of two teams before the 2002 season. Minnesota was the other franchise mentioned. When it was determined that the Twins were going to remain in place, contraction talk ended.

With no plan for a new ballpark in Montreal, Loria sold the Expos to Major League Baseball for $120 million in January 2002. Loria then bought the Florida Marlins for $158 million, and Marlins owner John Henry, along with partner Tom Werner and other investors, purchased the Boston Red Sox for a record $660 million.

MLB operated the Expos franchise for three seasons, looking for a site for relocation. A half-dozen cities were mentioned as candidates, but Portland and Washington, D.C. were at the forefront.

All of the same people who formed Portland Baseball Group’s steering committee for the 2001 House bill remained, with Kanter still doing much of the work.

“Steve was the mastermind getting the bill passed,” says Platt, a Portland businessman who was on the steering committee both times and contributed financially to getting things done.

The campaign for what would become Senate Bill 5 in 2003 raised nearly $500,000 including in-kind contributions, Kanter says. “A lot of business people came on board. Northwest Natural Gas, PGE, Nike, Platt Electric.”

“We put together a list of a couple of hundred businesses that officially endorsed the campaign,” Freeman says.

“A lot of people wanted this to happen for the right reasons,” Platt says. “No ego people in that group.”

Platt helped out beyond his financial contributions.

“He was a connector with other people,” Mahalic says. “Harvey would have been a candidate to be approached for minority ownership (in the MLB team).”

Frank Gill, an executive vice president at Intel, was among those who joined up. Attorney Jay Waldron did some work for the cause. Another was Wally Van Valkenburg, an attorney who was a member of the Oregon Sports Authority board. He became president of a coalition of groups that became the “Oregon Stadium Campaign.”

Wally Van Valkenburg

“The Sports Authority hadn’t been involved (in 2001) in any formal way,” says Van Valkenburg, now 72 and retired after nearly 40 years at Stoel Rives. “There was a feeling that it would be better for them to become involved in a partnership with the Baseball Group. Drew asked me if I would head up that partnership. We formed a new organization, a separately incorporated entity. It brought the resources the Sports Authority had together with the energy and passion the Baseball Group had.”

The Sports Authority, Mahalic says, covered lobbyist fees for the 2003 bid.

“Our lobbyists were called ‘the Victory Group,’ ” Mahalic says. “We talked strategy with them.”

“The lobbyists knew all the ins and outs of how to get the bill passed,” says Platt, now 75 and retired from his job as owner of Platt Electric Supply. “It was quite exciting.”

“Once we started getting traction, Drew’s people probably pushed him to look like they were taking over a bit,” Kanter says. “We ended up getting along fine, but there was some tension.”

Van Valkenburg would go on to serve for 10 years as chair of the Oregon Business Development Commission.

“He had a strong reputation as a person who could bring people together,” Freeman says. “That was a group that needed to be brought together, between the Sports Authority and Baseball Group. Bringing in an outside individual to take the lead and navigate the groups through everything was the best course of action. Wally and (OSA president) Randy Miller were leading the move to have the Sports Authority and Baseball Group collaborate and work together.”

David Kahn, a Portland native and former general manager of the Indiana Pacers, became the head the Oregon Stadium Campaign. When the Pacers built Conseco Fieldhouse, Kahn — now living in France and working as president of Paris Basketball — had been in charge of the design, the first retro-themed arena in the NBA, with a look like a basketball version of Camden Yards.

Oriole Park at Camden Yards

“We had the good fortune to have David show up at that point,” Van Valkenburg says. “None of us had any real-world experience in trying to build a major sports arena, and not a lot of experience in the world of professional sports. David had both of those. He was the day-to-day director, the guy who was putting it all together and helping us put together a credible plan.”

Not everyone agreed with Van Valkenburg on that. Some of those working with Kahn felt he was arrogant and condescending. Platt says didn’t know him well and didn’t have much interaction with him.

Says Platt: “But I heard someone in City Hall say, ‘I don’t know anybody who has met David Kahn who likes him.’ ”

Reached by email in Paris, Kahn failed to answer questions for this article.

With Kahn, Kanter, Mahalic and Lashbrook all involved, there were a lot of people inclined to want to take leadership roles.

“As the committee got bigger, there were a lot of different voices,” Lashbrook says. “There was some friction. But I respected everybody.”

“One of the challenges was, you had a lot of passionate people involved,” Campbell says. “Steve loves baseball. His enthusiasm was contagious. Lynn had his ideas, too. You had Drew and then David. You had the Portland Baseball Group and the Oregon Sports Authority and the Oregon Stadium Campaign.

“There was a bit of jostling, a bit of tension there for awhile as people jockeyed for ‘Who’s on first?’ I just didn’t want them in conflict. That wouldn’t have served our purpose. It worked out. Everybody got aligned around a common approach. They all cared about it. Ultimately, it was good to have as many advocates as possible.”

Says Van Valkenburg: “There were a lot of strong personalities, but everybody had a shared goal. Not everyone always agreed on the way we should go on things, but people worked pretty well together. We had a lot of good people involved.”

Eventually, Kanter says, “We sort of split things up to avoid civil war. Wally was the titular head. I did the legislation and David did the city.”

Kahn made a connection with Katz and became a special advisor to the mayor, spending a good deal of time in her office.

“The trouble with the city was, though Vera wanted baseball, they weren’t willing to do much yet,” Kanter says. “The city has to be cheerleaders, smooth the way, take care of some infrastructure. They weren’t ready to deliver much of that.”

► ◄

A streamlined version of 2001’s House Bill 2941 and Senate Bill 978 was co-written by Kanter and Harvey Rogers, a prominent attorney who specialized in municipal bonds and government financing, intended for the 2003 Legislative session. There was no sunset clause, a legal provision that sets a date for when the legislation automatically expires. If passed, the bill would be established in perpetuity.

“We believed we were in the driver’s seat for the Expos,” Platt says. “I had breakfast with Vera, just the two of us. She was quite optimistic, wanted it to happen and said all the right things.”

In January 2003, Ted Kulongoski succeeded Kitzhaber as Oregon’s governor.

“Kulongoski’s key person I worked with was Howard Lavine, who started out as Ted’s speech writer and became his arts, culture and sports guy in the administration,” Kanter says. “We worked with him closely and effectively, and Ted became a very enthusiastic supporter.”

Besides the Legislature, the Oregon Stadium Campaign had something else to worry about. Baltimore Orioles owner Peter Angelos had been claiming territorial rights in blocking Washington D.C.’s bid for an MLB franchise, but negotiations were underway behind the scenes. As a compromise, Angelos eventually agreed to give up his territorial rights in exchange for 90 percent of TV rights when Washington was finally granted a team for the 2005 season.

“Once Washington was in the game, our odds were small,” Kanter says. “We were now fighting uphill.”

“We knew from the start that if Washington decided to compete for the Expos, they would likely get it,” Van Valkenburg says. “We weren’t under any illusions about that. But it was really important for Portland to at least have the ambition to put a proposal together and not feel like we were too small or didn’t have the resources to give it a go.

“I got involved because I wanted us in Portland to consider ourselves a major league city. I was quite proud of the effort we put together.”

The OSC wanted to do an actuarial count of what revenues the state of Oregon would reap under the income tax bill if it got an MLB team. Michael Weiner, executive director of the MLB Players Association, provided the name, salary and “tax home” of every player.

“Taxpayers in the U.S. have one state at a time that is their tax home — normally where they maintain their permanent residence,” Kanter says. “How you pay your state income taxes depends on what states you earn money in and what state is your tax home.

“In 2003, there was not a single major league player paying income taxes to Oregon, so all of the taxes that would have been paid by home and visiting players would have been new tax revenue for the state. Interstate tax agreements are complex, so it was helpful to have the full list of tax homes and salaries to do an accurate tax forecast.”

In 2003, the average MLB team payroll was about $80 million.

“We did a careful calculation that showed that you could justify at least $250 million in bonds,” Kanter says. “We decided to take $150 million (for the stadium) and give $100 million for K-12 education.”

Kanter received a query from the head of the Oregon Department of Revenue. In Senate Bill 5, he inserted a provision requiring visiting teams from major pro sports franchises (including the NBA) to withhold eight percent of their pro rata payroll to give to the state of Oregon each year.

“How do we know the visiting players are going to pay?” the ODR head asked.

“What do you mean?” Kanter responded.

“How do you know they are going to file?” the ODR head asked.

Kanter: “If they are making millions of dollars a year, you don’t check to see if they file a tax return?”

ODR head: “No.”

Kanter: “What happens when Shaquille O’Neal comes to Portland with the Lakers?”

ODR head: “I don’t know.”

Kanter: “Do you realize that California has six full-time tax professionals tracking athletes and actors because there is so much money involved?”

“We put into the bill that we would withhold the amount of tax levied against players,” Kanter says today. “I don’t know if Oregon is collecting from NBA or pro soccer players, but legally we should be. According to the bill, the teams are required to do that. Whether anybody is enforcing that, I don’t know.”

► ◄

Lobbyists went into overdrive, emphasizing the merits of the bill to members of the Legislature.

“It was tough to sell,” Campbell says. “The House was easier than the Senate.”

“We did some outreach to legislators throughout the session by identifying those that were ‘maybe’ voters,” Freeman says. “The lobby team was key, but having a formal organization with the respect and credibility of the Oregon Stadium Campaign meant a lot to legislators, and hopefully to the governor’s office. Having that cohesive group with everybody at least externally on the same page — even though internally there was times of turmoil — was key to getting it passed.”

Many of the senators had never been to a Major League Baseball game. Through Platt, who had season tickets, OSC arranged for 16 of the senators to attend a Mariners game in Seattle.

“They noticed all the cars with Oregon license plates in the parking lot,”Kanter says. “It was effective. It took a lot of work to show them what benefit (having an MLB franchise) could have.”

The bill went through the House first, where the vote was 31-24 in favor. Then came the Senate.

“The initial vote in the Senate was five votes short,” Freeman says. “One of them was Senator Deckert, who changed his vote to ‘no’ when it was clear it wasn’t passing so he could request reconsideration. What that meant, that would give us potentially an attempt to have another vote.

“At the time, nobody there thought there was much chance of that happening. It was close to the end of the session. It seemed like that was it, that we had lost.”

They hadn’t.

“There was a last-ditch effort,” Freeman says. “There was a lot of work done behind the scenes with lobbyists trying to get the votes. We made some amendments (to the bill) to get votes. Suddenly, we were thinking, ‘There could be a chance of this happening.’ A few days later, it went to a vote and we got the ‘yes’ votes we needed.”

“It was all set,” Kanter says. “We had the votes. We had the commitment of everybody.”

But there was still one more hurdle. The Senate president was Peter Courtney, who had voted against the bill but agreed to allow it to go through. But Courtney was ill on the day the bill was to have been approved. Guess who presided as temporary president? Lenn Hannon.

“He could have killed SB 5 then and there,” Kanter says. “He certainly wasn’t for it. But quietly, he let the conferees be appointed as agreed upon, and the bill was on its way to final passage. I have always appreciated Senator Hannon for playing it straight at the end.”

Says Deckert: “One of my favorite moments of 10 years in Salem was when (Hannon) came in and told me he was going to let it go through the next day.”

The final tally was 16 for the bill, 11 against.

There was some celebrating from those who had worked on the campaign when the bill passed.

“I remember David calling me and telling me the bill had passed,” Van Valkenburg says. “I was thrilled.”

“I was euphoric,” Campbell says. “This is my 30th year of lobbying. That was probably the most interesting and fun piece of legislation I have had a chance to work on.”

► ◄

Once the stadium bill had passed and the money was appropriated contingent upon MLB granting Portland a franchise, there was more work to do.

Those who had pushed for the bill’s passage knew getting the Expos was anything but a done deal.

“We felt like we needed some luck with Washington D.C.,” says Deckert, 54, now working as vice president at Morrison Child and Family Services in Beaverton. “Washington’s (chances) were going to have to go bad, and then we would be sitting pretty. But we needed Washington to not happen.”

There was some skepticism that Major League Baseball was just using Portland as competition for Washington D.C., that it wasn’t a serious candidate for the Expos.

“We realized MLB is a business, that they were trying to get the best deal they can get,” Kanter says. “They like to have competing cities, for sure. D.C. was always on the (MLB) radar.”

But those with the Oregon Baseball Campaign didn’t think Portland was being “used” by MLB.

“When we were working on the proposal, given where Portland was at the time as a growing city with a vibrant economy and the largest market with only one of the Big Four pro sports, we should have been and would be a legitimate candidate for a team,” Van Valkenburg says. “We didn’t have an owner, but the feeling was with a credible funding package for a stadium, we would be an attractive market for MLB. If we were awarded a franchise, an owner would likely step forward and be willing to put a team in Portland.”

Mahalic had flown to New York City with Katz, Kahn and Kanter to make Portland’s case with MLB officials.

“I saw it as a legitimate fight, where we were the underdog,” Mahalic says. “At our meeting, they drew a circle around Washington and around Portland, and said, ‘There are nine million people here and two million here.’ Plus, the Senators had a long tradition in Washington. It was understood that every effort would be made to have it there, but we knew that if they couldn’t get a deal done there, we could make things work here.”

Kanter and Kahn attended a meeting with MLB’s relocation committee, including consultant Corey Busch, who was assigned to work with Portland and was the OSC reps’ main point of contact. The chairman of the committee Jerry Reinsdorf, owner of the White Sox. An updated version of Vataha’s “book” was presented to Busch and the six to eight owners at the meeting.

“It was the seminal book that made our case,” Kanter says.

Kanter says concerns were raised about Portland’s wet climate.

“We were not going to have a cover over the entire stadium,” he says. “We would get fewer rainout days than quite a number of MLB cities. There was the concern, of course, that if people around the state took the risk to drive into Portland for a game, it might (be rained out).

“Our plan was, we would have enough of the stands covered so that on a crummy April or May day, you would upgrade everybody to the expensive seats.”

MLB officials had also indicated they would give Portland an offset schedule, with fewer home games the first two months and more the rest of the season, “which (owners from) other cities were happy about because it was too hot in the summer months,” Kanter says.

As the issue was being discussed, Reinsdorf piped in, “Weather? Portland doesn’t have weather. Chicago has weather.”

“That got rid of the weather issue for us,” Kanter says.

In 2001, Vosmek had arranged for HOK Group in Kansas City, an architectural firm specializing in sports facilities, to draw up a plan for a stadium in Portland. (In 2009, HOK changed its name to Populous, the company contracted by the Portland Diamond Project for the current stadium proposal.) Several sites were looked at; most of the OSC officials favored the old Post Office spot between Northwest Hoyt and Broadway.

“HOK (officials) thought it was an excellent site,” Kanter says. “We even had them do a detailed design build for moving the post office to a parcel of Port of Portland vacant land at the airport to make room for the ballpark.”

But Portland’s bid for the Expos collapsed.

“We got outmuscled by Washington,” Platt says, and that was part of it.

“But the other weakness was the absence of serious city involvement,” Kanter says. “The city was sort of in there, but not really. It was definitely the weak link.”

At the end of the 2004 season, MLB announced the Expos were moving to the nation’s Capitol.

“It was tremendously disappointing that Senate Bill 5 didn’t result in (a stadium being built, or an MLB team coming to Portland),” Campbell says.

“I was disappointed that we didn’t get a team,” Van Valkenburg says, “but it was still an important step for Portland to take for the community’s sense of its own value.”

There was one last gasp. Loria was now the owner of the Marlins, who were playing their home games at Pro Players Stadium — home of the Dolphins — and were having trouble with financing for a new baseball stadium.

“We made a pitch,” Kanter says.

Tom Potter had just succeeded Katz as Portland’s mayor. Loria and a couple of associates flew to Portland to meet with the OSC group and Potter.

“There was some chance of them relocating to Portland, though small,” Kanter says. “When you look at our proposal, a big part of it was the legislation. Usually you have the city leading the charge. We never had that.

“Potter promised he would be open-minded, that he wouldn’t say anything definitive one way or the other. Then he went outside of the room (after the meeting with Loria) and told the press it was a ‘no.’ He went from neutral to being an impediment. He didn’t kill the deal, but we needed an enthusiastic mayor in support to have a real chance.”

In early 2005, the Marlins reached agreement in principle with the city of Miami and Dade County on a plan for a $420-million ballpark adjacent to the Orange Bowl. The Marlins finally moved into LoanDepot Park in 2012.

It signaled the end of the Oregon Stadium Campaign.

“Once the Marlins were committed to build their new stadium, we disbanded,” Kanter says.

And that, as they say, is the end of the story.

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.