Pat Casey: ‘My Hall of Fame is the dugout’

Updated 1/21/2024, 11:05 AM

CORVALLIS — Pat Casey is an old hat at halls of fame.

The former Oregon State baseball coach is already a member of three — The George Fox Sports Hall of Fame, the University of Portland Sports Hall of Fame and the Oregon State Sports Hall of Fame — and likely will soon gain entrance into the state of Oregon Sports Hall of Fame.

In addition, in 2009, Pat and wife Susan were honored as recipients of the Nell and John Wooden Coaching Achievement Award.

The big one, though, is coming up. On Feb.15 in Overland Park, Kan., the Newberg native will be inducted into the Collegiate Baseball Hall of Fame.

“I’m very honored by it,” Casey says during an interview at his Corvallis home. “I say that with much respect for the people who cherish athletics and what they mean. But I’m also well aware of why this happened, and how many people made this happen.

“My hall of fame is the dugout. I will accept this award on behalf of all the players, and the coaches, and the trainers, and the managers, and the doctors and all the people who were part of the Oregon State baseball program with me for 24 years. And I mean that. I don’t say it trying to slight this award at all.

“But I’m not overwhelmed thinking I’m a Hall of Famer. I’m a guy who was put into a situation and given an opportunity. I have full awareness the guys running that locker room and the guys in the dugout made this happen.”

Casey is 64 now. He retired his post in 2018 after coaching Oregon State to its third College World Series championship in 12 years, among the most outrageous of accomplishments in a sport in which pundits thought teams from the Northwest shouldn’t even be invited to the party.

“One of the greatest accomplishments ever in college sports,” says Jack Riley, Casey’s predecessor as head coach at Oregon State. “To have a team from the North win a national baseball championship? They said it would never happen.”

Actually, it happened several times in the 1950s and ‘60s. But not since Ohio State won it all in 1966 had a team from the northern U.S. won a national baseball title when Casey’s 2006 team ruled in Omaha. The Beavers did it again in 2007 and a third time in 2018, Casey’s final season.

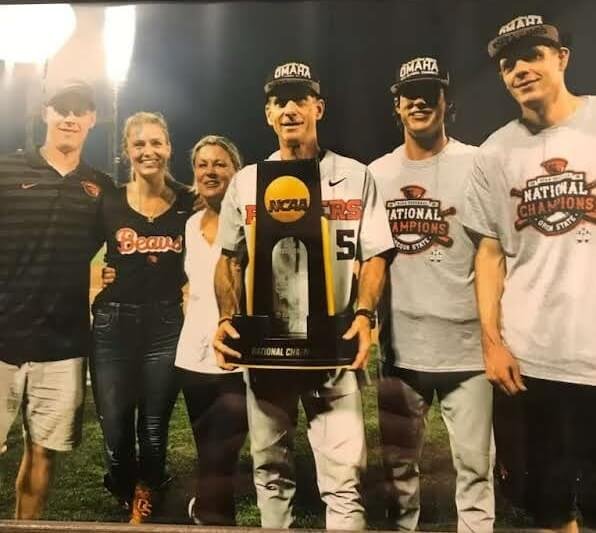

The Casey's celebrating Oregon State’s third national baseball championship — from left, Brett, Ellie, Susan, Pat, Joe and Jonathan (courtesy Pat Casey)

“It’s the most remarkable athletic feat I’ve seen in my life,” says Tim Hennessy, Casey’s close friend and a former OSU basketball player. “I don’t know that anybody has done what Pat did with our (geographical) location in any sport, ever.”

Over 31 seasons at George Fox and Oregon State — seven at George Fox, 24 at Oregon State — Casey’s teams won 1,071 games. At Oregon State, it was an even 900 against 458 losses. His Pac-10/12 record: 362-268. Casey’s OSU teams reached the College World Series six times and the NCAA Tournament 13 times. He earned five Pac-10/12 and five National Coach of the Year awards. In 2010, Baseball America named Casey Coach of the Decade. More than 100 OSU players were chosen in the MLB draft and more than 20 went on to the major leagues.

What truly sets Casey apart, though, is what’s inside.

“Character-wise, Pat is off the charts, with great morals,” says Pat Bailey, a Casey assistant for 12 years at Oregon State. “All a lot of coaches in D1 sports care about is themselves and what they accomplish personally. Pat was just the opposite of that. It was all about team. … he is a good friend and a great human being.”

► ◄

Casey received hundreds of calls, notes and texts from friends, former colleagues and many of those he faced on the diamonds over the years. The gist of the messages: Congrats. Well-deserved.

“I don’t think it’s something he needed to justify what he accomplished for the state of Oregon or for Oregon State,” says Darwin Barney, the second baseman on Casey’s first three CWS teams and his title teams on 2006 and ’07. “But I’m very happy for him to get that recognition. If anybody deserves it, it’s him.”

“It’s a no-brainer,” says OSU head coach Mitch Canham, the catcher on those same teams. “Case is the greatest.”

“It’s a great honor for him,” says Chris Casey, Pat’s older brother and head football coach at George Fox. “You want to earn things. He definitely earned it. You want to deserve things. He definitely deserves it. He’d be the first to tell you that individual awards come from team success, because of his humility and fact.”

“I’m so proud of Case,” says Ryan Lipe, an infielder on Casey’s first four Oregon State teams. “I care about him so much. Every one of us who played for him is thrilled.”

“If Case can’t get in,” asks Linfield head coach Dan Spencer, an OSU assistant under Casey from 1997-2007, “who can?”

“I love it,” says Frank Wakayama, an outfielder for Casey’s first George Fox teams in 1987 and ’88. “Pat is one of a kind. He has been a friend and mentor. I can’t say enough good things about him.”

Or as Brett Casey, one of Casey’s four children, succinctly puts it:

“It’s a pretty cool thing. He’s kind of a legend. It was bound to happen.”

► ◄

Casey isn’t sure how many family members will accompany him to the induction ceremony in suburban Kansas City, Mo. Pat and his wife of nearly 42 years, Susan, have four children — Jonathan, Brett, Ellie and Joe. Jonathan lives with his parents in Corvallis. Brett — who played baseball at OSU under his dad and also basketball for the Beavers — sells real estate in Corvallis. He and wife Jayme have two children. Joe, who also played for the Beavers under Pat, is head basketball coach at Colton High and lives in West Linn. Ellie, who lives in Lake Oswego, recently had her second child and may not be able to attend. Same for Pat’s parents, Fred and Bev, who live in Newberg. They are 89 and 88.

From left, Ellie, Joe, Susan and Pat (courtesy Pat Casey)

“I suspect most of my family will be there, including my immediate family,” Pat says. “My parents would love to go, but at their age, I don’t know if they can travel.”

Pat is the third of seven siblings. Mary Lynn and Chris are older. Julie, Tim, Brian and Colleen are younger. Bev had them in a torrid nine-year period. The Caseys were — are — a staunch Catholic family. Pat attends morning Mass nearly every morning.

“They’re Irish,” says Ron Northcutt, Casey’s best friend since high school. “They’re hotheaded. And they are competitive.”

Northcutt is the fourth of eight kids.

“We weren’t even Catholic,” laughs Northcutt, who played varsity football, basketball and baseball with Casey. “They were like my family. I spent a lot of time at their house. They treated me very well. All the guys were good athletes. To this day, I communicate with them.”

Pat was a three-sport star at Newberg High. Northcutt played varsity football, basketball and baseball with him.

“In high school, people wouldn’t really approach him,” says Northcutt, who would go on to play baseball with Casey at UP and then serve as an assistant coach for him at George Fox and Oregon State. “Not that he was a jerk, but he kept to himself. Once, the summer after high school, we went to a party, and all these people came up and said, ‘I can’t believe you guys are here, especially Case.’ But we liked to have fun like anyone else.”

Though he was a jock, Casey took his studies seriously.

“I taught algebra to Pat when he was a ninth grader,” says Sue McGrath, who has become a major donor to the Oregon State baseball program through the years. “He always came in right on time, sat in the front row and looked like he’d come from practice. He was a great kid, super smart at math, which I think helped him along the way in his career.”

The 6-1, 200-pound Casey played both basketball and baseball at the University of Portland. He then had an eight-year minor league baseball career as a first baseman and outfielder, his final three seasons at the Triple-A level. He hit .307 with 16 homers in 116 games for Calgary in 1987 but ended his career batting .215 in 48 games with the Portland Beavers in ’88.

After the Minnesota Twins released him, Casey returned to Newberg. Within a few days, he was asked if he had interest in the vacant George Fox baseball coaching job.

“No interest,” Pat told the George Fox rep. The school’s president, Ed Stevens, asked him to reconsider.

“He talked me into it,” Casey says. “A great man.”

Unfortunately, the job paid only $3,000. Casey, married and with two small children, needed more. For a while, he worked as a night janitor at a pizza parlor. He also earned a real estate license, though he had little time to sell property.

If Casey wasn’t busy enough, he also played a season and a half of basketball for the Bruins — at ages 28 and 29.

“The coach, Mark Vernon, had played city league against me and said, ‘You gotta play basketball for us,’ ” Casey says. “I had a year and a half of eligibility left. It was fun, but it was an extreme challenge. We often had to practice baseball real early in the morning. My players were amazingly accommodating.”

Casey missed the first win of his coaching career. The Bruins lost the first game of a double-header at Pacific. Between games, Casey returned to Newberg for a basketball playoff game against Eastern Oregon.

“During warmups, I’m told we won the second (baseball) game,” he says with a laugh. “Oh well.”

Thirty-one years later, Casey retired, having never served a day as an assistant coach.

Casey enjoyed six winning seasons in his seven years at George Fox, going 31-13 overall and 16-2 while winning the Northwest Conference crown the last season in 1994.

Wakayama transferred from Mt. Hood CC to play two seasons for Casey at George Fox.

“He was tough,” says Wakayama, who now owns a small business and lives in Happy Valley. “Not so much on me — I was an older guy who knew the ropes of college baseball. But he was always fair. That’s what I loved about him. He treated everybody the same and pushed you to be your best.”

“I loved my time at George Fox,” Casey says. “Sometimes it’s forgotten that it was a vital part of my coaching career.”

Through Casey’s seven years, George Fox played Oregon State six times, beating the Beavers 4-1 in Corvallis in 1992. Casey caught the eye of Riley, who was in the final years of what would be a 22-year run as Oregon State’s coach.

After the 1994 season, Riley retired. The Beavers had gone 36-15 and won the Pac-10 North in his final season. Riley was involved as an advisor for the selection committee that would recommend his successor to athletic director Dutch Baughman.

Casey was thinking he might want to coach one more year at George Fox before devoting himself to a career that could actually make some money. He was sitting in his real estate office one day when he received a call from OSU administrator Jack Rainey, who also served as commissioner of the Pac-12 North.

“Why didn’t you apply for the Oregon State job?” Rainey asked.

“I assumed they will hire Kurt Kemp,” Casey said.

Kemp had been Riley’s assistant for several seasons.

“Don’t sell yourself short,” Rainey told Casey. “You should apply. Would you apply if Riley encouraged you to? Jack wants the best guy for the job.”

Casey thought it over, then talked with Susan, who was all for him applying. Pat put a resume together, then drove to Corvallis to hand-deliver it to OSU officials. He was quickly named as one of four finalists, who would all get interviews with the selection committee.

“I told Susan, ‘If I can an interview, I’m going to get that job,’ ” Casey says. “When I found out I was one of four, we went to Washington Square. I bought a new tie, sports jacket, slacks and shoes. I told Susan, ‘Keep the receipts. If I don’t get the job, I have to return it all.’ And I still have the sports jacket.”

Riley, meanwhile, had a conversation with Kemp, who one day would become director of player development for the Atlanta Braves.

“I’ll support you if you’re the best candidate,” Riley told him.

“I put a lot of thought into it,” Riley says now. “I had called Donny (Wirth, the OSU alumni director) on the committee and told him, ‘Somebody better let Dutch know. He’s going to hire Kurt. Pat is by far the best candidate. We gotta go with Pat.’ ”

Associate AD Mike Corwin was executive director of the search committee. The other finalists were Kemp, former University of Portland head coach Terry Pollreisz and Bill Kinneberg, who was then pitching coach at Arizona State.

“I would say Jack hired Pat as much as anybody,” says Corwin, now retired and living in Corvallis. “He said, ‘You can do all the searching you want — Pat Casey is going to be your guy.’ Jack had tremendous respect for him.”

Riley had a talk with Casey, too.

“I do support Kurt, but I didn’t come here to work for 22 years to give my job away,” Riley told him. “I want the best guy to get my job.”

“There aren’t a lot of coaches who leave coaching who say, ‘I want it to be better than it was when I was here,’ ” Casey says. “I was really impressed with that.”

At one point on interview day, Riley took Casey to see the team’s indoor hitting facility at McAlexander Fieldhouse. It was August, “and hotter than hell,” Casey remembers.

“Jack opened the back doors, and there were all kinds of props from some play stored in there,” Casey says. “And there was a pole vault pit, and yellow foam was still in there. Jack was trying to move the props and fell into the pit. He’s a little banty rooster, anyway. He was cussing and trying to get around in there. I had to laugh.”

The committee agreed with Riley’s recommendation and chose Casey. Baughman approved the hire — perhaps the best one the school’s athletic department has ever made.

► ◄

It took awhile for Casey’s OSU program to gain traction. The 1995 Beavers went 25-24 overall and 14-16 to finish fourth in the Pac-10 North.

“We had some talent; we just didn’t have a lot of depth,” he says. “I could have done a lot better job that first year of being more flexible in how I saw things.”

The Beavers were much better the next three years, going 32-16, 38-12 and 35-14 overall. They finished second in the Pac-10 North all three years.

“I don’t think Case has ever lost his competitive fire, but over the years, he has channeled it a little differently,” says Lipe, now managing director for a MedTech executive search firm in Highland Park, Ill. “He wasn’t too far removed from his playing days when he was with us. A lot of us were blue-collar types, so he was a good fit for us.

“He instilled in us that every single thing mattered. He has always lived that. As soon as your feet touched the grass you had to run, no matter how much gear you’re carrying. We had to work harder than anybody else — outsmart them, outwork them. We were successful in doing that for him.”

“Case was in his late ‘30s and probably could compete with anybody on the field at the time,” says Jason Stranberg, an outfielder from 1996-98. “We were basically all Northwest guys. Things were very intense. The expectations to be a competitor and a teammate were very high. That’s what made us as a team at that point. Those are the kind of players he sought.”

Casey had a vision for the Oregon State program “from the get-go,” says Stranberg, now president of Adroit Construction, a company with 140 employees based in Ashland.

“He had every expectation for Oregon State baseball to be what it is today,” says Stranberg, who batted .397 as a junior in 1997. “He didn’t care where you came from. It mattered being a committed team member and competitive.

“Every pitch, every out, every inning — you just never stopped competing. That didn’t mean just in games — at practice, in the weight room, every step of the way. He had expectations to compete and be committed to what was happening. He was relentless about making that happen. Some players didn’t understand that. He wasn’t for every player at the time. I think he would say he had to adapt and mature as a coach.”

Lipe says even then, Casey had great balance in his coaching style.

“He pushed us really hard, but he cared about us,” he says. “He knows life is easier if you do the things he teaches. I’m talking about your effort, your attitude, how you approach things. If you’re able to show you care about the people you’re leading, they’re going to do a lot of things for you.

“He talked about doing what you’re able to control. You can control your effort; you can control your attitude; you can control how you treat people. And there are lot of branches off of those. You can’t control the weather, but you can deal with it. You can control how you treat people in a positive way. That’s how you end up in the Hall of Fame. He was able to live it and breathe it.”

Stranberg learned responsibility the hard way on one road trip.

“He left me and a couple of other key players at the hotel one morning because we got stuck in a line trying to pay for breakfast,” he says.

After Stranberg had a sub-par sophomore season at the plate and in the classroom, Casey sat him down in his office. A walk-on, Stranberg had asked for some scholarship help.

“Strannie, I have to recruit a centerfielder,” Casey told him. “Hitting .280 and not passing classes won’t cut it for me. You have to make a decision whether you’re going to be serious about this or not. I believe you have more in you for yourself and your team. You have the ability to go earn this. Do it, or don’t.’ ”

“Case had the foresight to put me at the crossroads at that point in my life,” Stranberg says. “It was transformative for me. Those were fair expectations. Thankfully, I stuck with it and became a good student, got my engineering degree, and he made me a competitive athlete and a successful player at that level. He forced me to make life choices, realizing that’s what life’s about.

“With Case, every day was a life lesson. He is probably tired of hearing me thank him for the impact he has had on me as a professional in my business, but most of all as a father and a husband. He was a huge influence in every part of my life.”

Lipe has a similar story. In a one-on-one with Casey after fall ball his freshman year, he said his life plan included becoming a physician.

“He was like, ‘That’s a new one for me. I’m going to have to get back to you on that,’ ” Lipe says.

“A week later, I meet with him. He says, ‘You know what it’s going to take to get into med school? The stuff you have to do in the summers? If you are ready to take the challenge, I’m with you. I met with your counselor and we’ll stay in touch about it.’ ”

Second term his sophomore year, Lipe got a 2.9 gpa.

“He called me in and said, ‘I thought we had a commitment to this. Do you think a 2.9 is going to get you into med school?’,” says Lipe. “I said no. He said, ‘I can tell you this. You’re going to be doing all the work from now on. I’m going to make sure you do all your work.’

“I never got below a 3.3 the rest of the way, and I did ultimately get accepted to medical school and went for a while. He cared that much about all of us outside of baseball.”

Casey’s direct style and demands for commitment were too much for some players.

“He probably lost some folks who had the talent to play there but didn’t have what he required out of his players — to be fully committed to your team, your studies and everything else,” Lipe says. “I’m assuming he changed the profile of how he recruited later. I know he would say, ‘I’m not going to lower my standards because a player can’t handle it. I’m going to make sure they can handle the things we expect here.’

“As the years went on, he probably loosened up quite a bit more and was able to pick those type of athletes who were a little grittier. He expected the same type of commitment from everybody.”

Corwin says it’s a coaching trait Casey shared with Jack Riley.

“There are a lot of players both of them had who either loved him or hated him,” Corwin says. “Maybe not a whole lot of in between. Most of the guys who hated him, after they were gone for a year or two, they saw how they had changed during the experience under Pat and truly became men.

“You can see it in OSU baseball’s ‘Dugout Club,’ when we have golf tournaments. The allegiance to him is so tight. Once you’re a Beaver baseball player, you’re one for life. It’s quite a cult.”

► ◄

Goss Stadium opened in 1999, the year Oregon State began full Pac-10 play. Before that, the Beavers played at Coleman Field, on the same plot of land but in a different world than Goss. The field was named for Ralph Coleman, the school’s head coach from 1923-66.

“You had sunken orange dugouts, where if you stood up too quickly you hit your head,” Casey says with a laugh. “A press box that had six pieces of plywood painted orange with a Beaver on the side. Wooden bleachers.”

“They barely had uniforms,” McGrath says. “They were going on a shoestring budget.”

The McGraths were there to help, just as they were during the Riley era. The press box at Goss is named in their honor.

“The McGraths were vital toward keeping the program going and improving our facilities,” Casey says.

In the early years, the Beavers weren’t exactly selling out at Coleman Field.

“We had our Dugout Club meetings at Burton’s Restaurant,” Casey says. “I’d go there every Friday during the spring and give away tickets to get people to go to games.”

Casey wasn’t complaining.

“When I played at Portland U. or coached at George Fox, I always loved coming and playing here,” he says. “The field was always nice. In my mind, I was in a major league park. Jess Lewis was the groundskeeper. I had people who mowed the grass. Jess and I were down there at midnight sometimes pulling the tarp on together. We had to do it all.”

That included fund-raising.

“Case went out and raised all the money by himself for the stadium,” says Hennessy, a principal consultant for an insurance company in Corvallis. “That first year, he came to me and asked if I would buy five seats and make a $1,000 commitment for five years. He had a vision and saw it. The fund-raising never stopped, year after year. He built the foundation of the program brick by brick.”

“I had to fund-raise a whole bunch in the early stages — from 1995-99, more than I should have done,” Casey says. “Dutch was honest with me. He said, ‘I’m going to give you autonomy to run your program. If you can find money, good for you. I need to get football turned around. That’s my focus.’

“So off we went. Every little thing we did — like getting a Nike contract — was important. We just had so many good people decide to support us.”

Including John Goss, a real estate magnate who donated a piece of property worth $4.5 million. The sale went to construction of Goss Stadium.

Pat Casey and John Goss during groundbreaking ceremonies at Goss Stadium (courtesy Pat Casey)

“In the old ballpark, there was no way to compete in the Pac-10 with the teams in that league,” says Dan Spencer, who coached in Casey’s staff from 1997-2007, the last four seasons as pitching coach. “He hustled it. He talked to the right people. He grinded it out. He stayed with it. That got us started.”

When the new stadium opened, “That was huge,” Casey says. “Our locker rooms had been in Gill Coliseum. There was no place to go at the park.”

Goss underwent an expansion in 2006 and another in 2018. The first artificial turf was installed in 2007.

“Every year we did something to improve the facility,” Casey says.

Goss was necessary for Casey to realize his dream of playing in a unified Pac-10.

“That dream was to not play all the conference games in the Northwest,” he says. “I didn’t see how we could ever grow without building a stadium and getting into the league. We started pushing. I didn’t have a lot of support from coaches in the North at first.”

Casey’s main goal was to get in position to have a legitimate shot to make the NCAA Tournament each year. In 1998, South coaches agreed to play nine inter-conference games against each of the North teams.

“They said, ‘They won’t count in league standings, but they’ll help your RPI,’ ” Casey says.

That year, Oregon State won one of three games at eventual national champion Southern Cal, swept a three-game home series against top-10 team Arizona, then swept another three-game home series against a UCLA team featuring Chase Utley and Eric Byrnes.

“We’re 35-14 and go 7-2 against the South and we don’t get in,” Casey says. “That club was good enough to have a chance to play in the World Series.”

The conference unified in 1999.

“That was the big break we needed,” Casey says. “You go to recruit a kid and he’d ask, ‘You’re in the Pac-10 but you don’t play Stanford or Arizona State?’ ”

The Beavers went through some growing pains, going 7-17 in ’99 and 9-15 in 2000.

“A lot of the teams from 2001 to 2004 were so close; we just didn’t have the depth, especially in the bullpen,” Casey says.

The breakthrough came in 2005. Led by juniors Jacoby Ellsbury and Tyler Graham and senior Andy Jenkins and featuring sophomore Mitch Canham and freshman Darwin Barney and the sophomore pitching quartet of Dallas Buck, Jonah Nickerson, Anton Maxwell and Kevin Gunderson, the Beavers went 46-10, won the Pac-10 and reached the CWS for the first time since 1952.

“There was a lot of pitching in the state two years in a row, and we benefitted from that,” says Spencer, now in his fifth year as Linfield’s head coach. “The whole thing with Case, though, was to stay with it. A lot of it was his personality. The biggest part of that is flat-out toughness. We had some good teams in ’97 and ’98, but playing on an island in the corner of the country, nobody knew how good we were. You didn’t get the respect you thought you should.

“His (Christian) faith is a huge part of it. He stressed being able to stay with it and believing that if we keep showing up, one day the door is going to open. And it did. And he did a great job keeping that thing open for a long time.”

Casey will never forget the feeling of visiting Omaha’s Rosenblatt Stadium for the first time as coach of a participating team in 2005.

“When that bus pulled up for our first practice and we walked down the tunnel and I stepped on the field … wow,” Casey says, smiling at the memory. “Of all the things I had done, it was one of the most gratifying moments of my life. I can feel it right now as we talk. I remember the first step. I know what I was wearing. I know what I thought. It was amazing.”

The 2005 Beavers went 0-2 and were eliminated early at Omaha.

“We’ll be back next year,” Gunderson promised in a post-game press conference.

Casey felt the same way.

“I think of the people who followed Beaver baseball for so many years who were so fulfilled, so proud that we just made it to Omaha,” he says. “They really wanted something good to happen. It had been 50-some years. I’ll never forget how excited and happy they were. It was almost like they were saying, ‘We got here. We’ve done it.’

“To me it was like, ‘No we haven’t done it.’ There is no doubt the guys felt the same way. We didn’t go to Omaha to play; we went there to win.’ ”

► ◄

Oregon State reloaded in 2006, going 50-16 overall and 16-7 to successfully defend its Pac-10 title. The Beavers won five straight Regional and Super Regional games to reach Omaha again, but fell 11-1 to Miami in their CWS opener. Facing elimination, the Beavers won four straight to reach the best-of-three finals against North Carolina, to whom they fell 4-3 in the opener. They came back to win two and claim the school’s first-ever national baseball championship and second in any sport (joining cross country in 1961).

The Beavers became the first team ever to face six elimination games in the CWS; also to win the title despite losing two games.

“We got our asses handed to us in the opener by Miami,” Casey recalls. “I’ll never forget. I thought, ‘All these guys have to do is win a game and they’ll know they belong. We just gotta get over the hump.’ We beat Georgia behind some phenomenal doubleplays by Chris Kunda and Barney and a great pitching performance by Nickerson and Gundy to close.

“Then we got Miami again. We’re hitting in the cages before the game, and (Miami coach) Jim Morris is sitting there talking to (broadcaster) Erin Andrews. I was trying to ask him who he was going with to pitch — the right-hander or left-hander — and he kind of sloughs me off with, ‘Aw, it doesn’t matter.’

“So I got the guys together and said, ‘Let me tell you how disrespected I was. He doesn’t think this is a going to be a game.’ Then Mike Stutes dialed it up and we rolled them (9-1). We go 18 innings against Rice and don’t give them a run. That one was unique. We were so tired, so stretched out with our pitching. It was all warrior mentality.”

In 2007, they returned to Omaha and did it again, though in different fashion. The Beavers finished 49-18 overall but were only 10-14 in conference playing, tied for sixth in the standings. After starting the season 23-3, they were swept in a three-game series by Arizona. It happened again against Arizona State.

The Beavers opened the postseason as the No. 3 seed in the Charlottesville Regional and lost their second game 7-4 in 13 innings to host Virginia. They went on to win their next 10 games, sweeping five games at Omaha to successfully defend their 2006 crown. The Beavers trailed for only one inning in that CWS.

“We struggled a lot of that season,” Casey says. “That Arizona State team was maybe the best college team I’ve ever coached against, with future major leaguers like Brett Wallace, Eric Sogard, Ike Davis and Mike Leake.

“At Charlottesville, we beat Rutgers and lost to Virginia, but we were starting to play pretty good. I told the coaches, ‘If we win tomorrow (against Rutgers again), we’re not going to lose another game.’ We got a rainout, which gave us an extra day to rest and prepare, and then beat Virginia twice. Then it was the easiest five games you could have in the CWS.

“In 2006, it had been such a struggle. In 2007, I don’t know if I’ve ever had a team that was in such a rhythm playing the game together. We got on this fantastic roll. It was like, ‘Just go play. I’m going to watch you guys win this thing.’ ”

The final championship came in 2018, and again, there were six elimination games to overcome. The Beavers stand as the only CWS team to face six of them and win a title — and they have done it twice.

Oregon State was 55-12-1 overall and 20-9-1 in Pac-12, finishing second in the conference. The Beavers swept five games in the Regional and Super Regional, then lost the CWS opener to North Carolina 8-6, sending them to the losers’ bracket at TD Ameritrade, Omaha’s new ballpark (it is now called “Charles Schwab Field”). Four straight wins got them to the best-of-three finals against Arkansas. The Razorbacks won the opener 4-1; the Beavers took Game 2 by a 5-3 score in the most dramatic fashion possible.

Beaver Nation will never forget the ninth-inning, two-out pop fly off the bat of Cadyn Grenier in foul ground down the first-base line that fell between three defenders, with Arkansas leading 3-2 and ready to celebrate a CWS title. Or Grenier’s long at-bat that ended with a single to score pinch-runner Zach Clayton from third base and tie the score at 3-3. Or Trevor Larnach’s ensuing two-run homer to right to push the Beavers ahead 5-3. Or Jake Mulholland closing the Razorbacks out in the bottom of the ninth for the victory. Or the next day, Kevin Abel’s complete-game masterpiece as the Beavers rolled 5-0 in Game 3 to wrap up an improbable — almost impossible — finish.

“The dugouts are very long at TD Ameritrade,” Casey says. “When Grenier’s pop went up, I never thought it was going to be in play. I never had the anxiety everybody else did. I couldn’t see the ball. When I stood up and looked for it, I didn’t see it until the ball hit the ground. I looked over at Coach (Dave) Van Horn. He crossed his arms and acted like nothing was going on, but I know what he had to be feeling. You can’t give somebody another chance like that.

“Grenier was a guy who was so hard on himself as a hitter. He put up a battle that was amazing to me. Then Larnach knocks one out against a left-hander — wow.”

By the bottom of the ninth, Casey had used every position.

“I had Joe Casey in centerfield, Clayton in left, Andy Armstrong at third base, and Michael Gretler had moved from third to first,” Casey says. “But we’d always said, great teams come when the best player on the team makes the player with the least talent feel as important as him. All those guys felt like they belonged at that moment. That was rewarding.

“After we won Game 2, we had the same feeling we had when we beat Washington (to stay alive after losing to North Carolina). We were going to win it all.”

Casey has a photo of the Beavers walking dejectedly off the field during the 2017 CWS after LSU had flipped the switch on them, beating them twice after Oregon State had crushed them 13-1 to send the Tigers to the losers’ bracket.

“That picture says it all,” Casey says. “That was the day we won the 2018 national championship. Just like in ’05 when we walked off the field after losing to Baylor.”

Casey can’t rate one of this three titles over the other.

“They are all independently special in their own way that the other one couldn’t match,” he says.

Casey’s best team, though, was the 2017 club.

“The record would certainly indicate that,” he says. “It very well could have been.”

Oregon State was 56-6 that season — 56-4 going into the final two games against LSU. The Beavers rolled to the Pac-12 regular-season title with a record of 27-3.

“I don’t think we’ll ever see that again,” Casey says. “The best team is the one that wins the last game of the year. We didn’t do that. It could have been our best team, and circumstances kept us from becoming the best we could be.”

Luke Heimlich — the Pac-12 Pitcher of the Year with a nation’s best 0.83 ERA — recused himself from participation after the Regional while dealing with ramifications of adjudication of a child molestation case involving a niece that became public. Left-fielder Christian Donahue failed a drug test and was unable to play in the CWS. In an elimination game against LSU, a home run by Steven Kwan that would have tied the score at 2-2 was ruled foul.

“The NCAA later said it should have been reviewed,” Casey says. “We had begun review that year but it was limited.

“But I don’t ever look at those and say that’s the reason we didn’t win (a championship) that year. It’s very difficult to win games over and over. But we were playing very well. We felt like we could have won the thing.”

► ◄

In Casey’s early years at Oregon State, most of his recruiting was in the Northwest. That changed as the program’s profile went national.

“After we won the second championship in 2007, we were able to recruit in areas we never recruited before,” he says.

After a disappointing 2008 season, though, Casey changed his approach.

“We had our highest recruiting class that year — No. 3 in the country — but things didn’t work out the way I thought they would,” he says. “After that, we made a concerted effort to recruit the area between middle of California and the Canada border. We would recruit individuals in areas, but not the areas themselves.”

Mostly, Casey and his staff were looking for “OKG” players — “our kind of guys.”

“There were certain out-of-state guys who had a hard time with the weather, especially in the early years,” Casey says. “But as we got better, that got better. They didn’t love the weather; they just loved being here. And our facilities improved so we could practice indoors and play almost any time. From about 2012 on, it didn’t matter about the weather.”

About that time, Arizona coach Andy Lopez said something about Oregon State baseball that has stuck with Casey.

“They’re not going to beat you on paper,” Lopez said. “They’re just going to beat you on the field.”

Says Casey: “I said to our guys, ‘Do you understand what he means? He’s saying, these guys may not profile out at Vanderbilt or Texas, but they just go out and win.’ It was one of the greatest compliments you could have.”

When asked about Casey’s attributes as a coach, most put competitiveness at or near the top of the list.

“I’ve never met anybody who was a better competitor than Case,” Wakayama says. “Playing hoops against you, whatever, he didn’t care who you were. He was going to win.”

“I definitely get that from my father,” Casey says. “And also from my brother Chris, who was a tremendous competitor. He was always the best athlete through junior high. In high school, he decided he wanted to be a football player. I just wanted to play them all.”

Chris is almost exactly a year older than Pat. Growing up, they were like twins.

“We played sports together,” says Chris, who has been George Fox’s head football coach for 10 years. “We fed off each other. We competed against each other. We had knockdown, drag-out one-on-one basketball games at the house. I remember Dad throwing passes to us, and playing tackle football at my grandparents’ house. Pat would run a route and I’d cover him, and then we’d switch roles.

“Dad was the main source of the competitiveness thing, for sure. We all got some of Dad in us. I know I dislike losing more than I like winning. Dad is Christian with an attitude. Back in the day, he got into a few fights. With the Caseys, if you’re fighting one of us, you’re fighting all of us.”

Says Bailey: “Some of the coaches we played against had a hard time with Case because he was so competitive. He was one of those guys you love on your side and opponents hate because he’s so competitive.”

Pat developed his baseball system early in his years at Oregon State.

“When I was at George Fox, I wasn’t thinking a whole lot about how do I run a program and win games,” he says. “At Oregon State, I created a philosophy, which was shrinking the game. Our offensive philosophy was ‘get ‘em on; get ‘em over; get ‘em in.’ Our guys were committed to that. If you want to hit and run or bunt, the only way to do that is defend and pitch. I can coach and manage and make things happen if it’s 3-1 or 3-2, but if you’re down 8-1 you can’t do that. There are days you can’t hit, but never days you can’t commit to defending.

“Pitching is the same way. We started going after quality arms and having weapons of all kinds — right-handers, left-handers, set-up guys, closers. No way we were going to succeed unless we could get into a close game with Stanford or USC. Once we did that, we proved we could execute. Then we were able to start recruiting players who could tie both the offensive and defensive ends together.”

Riley watched the evolution of the Casey era with interest.

“Pat had a unique way of using fear as a coach — not in a militant or rough way,” says Riley, 85 and retired in Corvallis. “He put a lot of discipline behind the strike zone. It was ‘show it or you sit.’ When I first started seeing the strike zone change with Pat was with Jacoby Ellsbury. As a freshman, his strike zone the first couple of weeks was everywhere. By the end of that season, it had completely changed.

“Pat used the strike zone for defense and pitching, too. When he was going really good, his teams never beat themselves. From about 2005 until he retired, I couldn’t count more than a half-dozen times that happened. If they needed something done — the big hit, the big pitch — more often than not they’d get it. And they didn’t beat themselves with errors, wild pitches. It was fascinating to watch.”

Casey had many chances to leave Oregon State for a more high-paying job. In 2006, he visited Notre Dame. Phil Knight donated some money to ensure he stayed in Corvallis. Texas came calling. So did Oregon after the Ducks resurrected baseball.

“Start picking the SEC schools,” Hennessy says. “There’s a list of places he could have gone that is longer than your arm.”

“Case had me respond to all emails,” says Northcutt, OSU’s director of baseball operations for several years under Casey. “I saw the salaries being offered.”

Casey turned down LSU for a second time in 2021. A major reason was son Jonathan, now 38, who is autistic and is also in the running for the most popular person in Corvallis. Everybody in town knows him. He is comfortable living there.

“I’m not sure I could enjoy it knowing the difficulty it would be to displace Jon from an environment in which he’s so safe,” Pat says. “The other part of me felt like it would be hard for me to be a head coach at another institution than Oregon State. I’m so glad that I spent such a big part of my career here.”

Pat and Susan say they have learned more from Jonathan than he has learned from them.

“They talk about special needs — we need special people,” Pat says. “Jon is a special person. His challenges are our challenges. I wish I could have the influence he has on people. I‘ve never seen a guy who has influenced more people, been such an inspiration to so many.

“Everything about him is genuine. We have to be worried about tomorrow. With Jon, everything is real. It’s truth. It’s how he feels. He knows instinctively whether people care about him. He’s a warrior, man. On top of that, he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at 16. Having to go through that has not been easy but he has handled it. And he’s a competitor. The good Lord might not have given him all his faculties, but he has the one that says you had better compete.”

► ◄

Coaching is so much about relationships. Casey has made many — with players, with coaches, friends, donors, even the occasional sportswriter.

Some of their observations:

PAT BAILEY (served as an assistant on Casey’s staff from 2007-18, was interim head coach the year after he retired, now works as Willamette Valley director for the Fellowship of Christian Athletes): “I loved working with Pat. He cares about young people. That’s what he was all about as a coach. He was all about molding men.

“He’s a man’s man. He’s going to be upfront and honest with you, and that didn’t bother me. There were times when it was a little uncomfortable in our coaches’ meetings, but I don’t like people beating around the bush. He did it because he wanted the best for our coaching staff, our players and our program. If you’re not in it to be the best, then get out. We didn’t talk about wins and losses. It was about the pursuit of excellence. All that other stuff will take care of itself.

“Case was the best motivator I’ve ever been around. He did a great job evaluating each player individually according to talent and personality. He could have been a sports psychologist. As a recruiter, I called him ‘The closer.’ We’d bring guys in and he’d close them. He was good with in-game strategy. He was really smart about looking at odds and making good decisions that way.

“He always came up with great one-liners. During Kyle Nobach’s first year, he was struggling and was kind of a mess. One day we were in the batting cages and Kyle was fretting. Case said, ‘Hey Kyle, why don’t you cut your head off, stick it in a jar and stare at it for an hour?’ He was saying, ‘Quit thinking so much and just hit.’ After that, Kyle did.”

Darwin Barney was the shortstop and a catalyst of three straight College World Series appearances — and two championships (courtesy OSU sports communications)

DARWIN BARNEY (played for Casey from 2005-07, had an eight-year major league career, coached under Canham from 2020-23, now living in Lake Oswego and running baseball camps and clinics): “I liked playing for Case a lot. We had a different kind of relationship. He was always very intense, that guy who always brought that energy. If he felt you didn’t care as much about the game as he did, it was tough to have a good relationship with him. But if he felt you did care as much about the game, which I did, it was very easy to get his respect. He knew I had the same desire to win. He could be tough to play for if you weren’t as invested as he was. He was ultra-invested. If you get 30 guys rowing the boat in the same direction and have a guy like him out in front of them, great things can happen.

“Some people have said I helped him enjoy the game a little more and made it fun. Little things like, in an insanely intense moment during a game in Omaha, I flicked him on the ear in the dugout. You have to not be scared of the guy to do that. We have a great relationship to this day.

“He could be intimidating. He demanded perfection at times. He was hard on guys. He challenged them. But ultimately, he built guys up. Some people have a hard time with those expectations. Eventually when he got a bunch of guys around him with the same goals, that’s when stuff took off.

“He was special at recruiting. When you become who he was, people want to play for a guy like him. A big league manager walks into a room and there’s a presence about him. He has that. There’s that positive energy. You can feel that. When you can feel someone’s presence, it makes a huge difference in recruiting, how parents feel about giving their kids to you. His presence is huge. He exudes confidence.

“Recruiting and fundraising, that’s college baseball. He’s good at connecting with people. His presence is huge. Being able to go on stage and talking to people correctly and getting your point across the right way, it’s very important. He could command a room. He was very good at that. His morals, his family code, what he stood for — all those things helped.

“There are many success stories where coaches built a winner, but Case built something that was sustainable. Eugene turned into the running capitol of the country. He has built that with Oregon State baseball. He has built a culture that will last. Even after he is gone, the team is still successful. It takes something special to build things that last. “Anybody can find lightning in a bottle once. When you’re authentic, things can be lasting. When I was coaching there, we were trying to live up to his standards, true to what he built and taught. It gives you easy guidelines to follow and create success out of it. It’s hard to imagine anyone doing what he done as well as he did.”

MITCH CANHAM (played for Casey from 2004-07, head coach at OSU from 2020-present):

“I remember coming to Corvallis on my recruiting and meeting Case and the other coaches. They were very blue collar. A tough coaching staff. Feisty. They could be mean. They were competitive. I go, ‘perfect.’ I loved it. All big, firm handshakes. They’d all worked on the field. They looked you in the eye. Dirt under their fingernails.

“After I got there, I enjoyed the difficult conversations Pat would have with us. Some people looked at it like he was being mean. I looked at it like he cared. He would throw the meanest (batting practice) that you’ve ever seen. You get him fired up, he would throw that ball a zillion miles an hour. When Case was throwing BP, you wore a helmet. You didn’t want to be the guy who got beaned by him.

“Case is about humility and genuine care for his players and his program. He showed a lot of us how to play the game, but also how to stand tall and be courageous. He also taught us how to take care of family.

“Big Jon and I are the same age. One of the most iconic images I can think of is Jon and Pat embracing on the field after winning the World Series in 2005. We see how much Pat cares about his family. It’s about making sure they are all well-taken care of, making sure they are all loved. As busy as a job as this can be, he is out there throwing BP to his kids or spending time to take them out to dinner.

“One of the hardest things to do as a coach is to shut it off. Over time, helped me learned how. You are leading by example. Showing them how to work, to be diligent. We talk all the time. He’s a strong mentor of mine.

Case lives a mile from the stadium. With everyone he has influenced over the years in such a tremendous way on and off the field, we are so lucky he’s still around here and can be a huge mentor for all of us. You know how many lives he has transformed over the years. You want him around all the time — not just for baseball stuff, but for handling adversity, affecting creativity and moving the needle forward. I could talk about Case non-stop until he came in and told me to pipe down.

“That said, I am not Case. I understand his greatness, but I am not him and I am going to do things a little differently. There were times he would express things a little more vocally than I do. But I learned a lot about focusing on the people from Case. It’s a conversation we have had quite a bit. Don’t worry about wins and losses. Focus on the people. I find that has carried me into a lot of what I do in life and how I coach. We have had a strong relationship since I came to Oregon State. It is a special place and it has been that way in large part due to Pat Casey.”

BRETT CASEY (The second of Pat’s three sons): “He was great as a father while I was growing up. He coached me in basketball. He made time to do that. That started while he was at George Fox. At Oregon State, I was around him 24/7. I was always out there at (Beaver baseball) practice. He would hit me groundballs and pitch to me after practice. I know he hated missing some of my games later on when he was playing.

“Maybe his biggest attribute is resiliency. He is about as tough as you can get. There is nothing that is going to stop him. He went from being a janitor to pay some bills at George Fox to coaching at Oregon State. He turned the field from a chicken wire fence with wood bleachers to one of the best stadiums on the West coast. He is not going to be denied.

“I am proud of the role he has taken on since he retired from coaching. He is around my kids all the time. He takes time to watch them. He helps any way he can. He and Mom did a great job raising us kids and turning us into good human beings and faith-driven people.”

CHRIS CASEY (Pat’s older brother): “When you look at leadership as a coach, you want somebody who will develop people for life and teamwork skills, and you want somebody to develop players and the program. That’s exactly what Pat did at Oregon State, and what he stands for. He is the kind of man you want coaching your son.

“He is a flat-out hard worker. Hard work is a great equalizer. You might say Arizona State or UCLA or USC has an advantage over Oregon State because of weather and tradition, but nobody is going to outwork the guy. He has tremendous values, character and integrity. He always was willing to learn and to take time and refine and improve on what you do. He is relentless at learning. He is as much about a philosophy of life as he is about coaching.

“Pat is a devout Christian within his Catholic faith. He has mental and physical toughness, but people would be a little surprised at how soft he is inside. He sent me a video the other day of Jim Croce’s son being interviewed. A.J. lost his dad at age 2, his sight at age four and his wife to a heart condition. In the video, he talked about the important things in life that his dad left him, the values and meaning of his dad’s songs. They were ballads about life and family and closeness and relationship. Pat said, ‘Here’s a neat story.’ And we had a conversation about life and stuff.

“Pat cares about people. Once he saw a lady in a store and she didn’t have enough money to pay for something. He could tell she was needy. He pulled out a $100 bill and gave it to her. She started crying. He would be the last guy who wants that made public, but that shows what kind of a guy he is. He is a humanitarian from the word go.”

SUSAN CASEY (Pat’s wife): “Pat did a really good job balancing his job and family life. He was always there when he could be. I’m sure most college coaches miss a lot of their kids’ games. Pat never missed one if he could avoid it. He went to all the kids’ events any time he could, or would take the extra time to set practice early or late to be able to go. The job also had a lot of perks for the kids, too. He did a good job of juggling all of that. We didn’t ever feel we missed out.

“There was no doubt about the dedication and loyalty to coaching and the time he put into it. There are a lot of things he missed out on socially because he needed to coach. He wasn’t going to slide on that at all. We always laughed when we went on vacations in the summer. He was coaching 24/7. He never really was away. It was always on his mind.

“At the end he was just getting tired of the grind. It was wearing on him all the time. His team was No. 1 and he really couldn’t get away from it. He got offered jobs at a lot of places, too, but he was not going to play another school against us. After he had been away from coaching for a while, I thought he’d take (the LSU job). I was on board, because I like to go and do new things. But I don’t know if he could have put his whole heart and soul into another school.

“Pat has that fiery, competitive spirit, but there is a very quiet side to him. He likes to be by himself a little bit. When you are so out there as a coach and everybody sees what he does, sometimes you do want to get away.

“I’m proud of the coach he was. The husband that he is. The father that he is. The man that he is.”

TIM HENNESSY (friend): “Winning three national championships has been a blessing for Pat, but in a way, not a blessing. He doesn’t want the attention that comes with that at all. He is so full of humility, so full of his faith, so full of his family. Taking care of Jonathan is one of the big reasons he’s still in Corvallis. With a lot of coaches, they are gone so much their family situation doesn’t work out. Pat was around. He wasn’t Pat Casey with his kids. He was their dad.

“You are blessed to have a guy like that in your life. He is not a saint, but he can motivate people. His teams completely overachieved year after year. His competitiveness was not overbearing. He can read people and knows how to motivate people. It was never about Pat. It was always about the players. Kids will run through a brick wall for you if they know it’s about them instead of you. That’s his biggest attribute before anything else.

“Pat doesn’t leave anybody behind. People respect his loyalty. He does what he does to try to make his players a better son, a better father, a better teammate, a better person later in life.”

RON NORTHCUTT (friend): “Pat has that ‘it’ factor. He has a huge heart. As a coach, he was a disciplinarian, but he would also slap a kid on the ass and pick him up in the next minute.

“On a road trip to L.A. one year, he saw a gal sitting on a bench in front of a market. She didn’t look so good. He said, ‘Are you OK? Are you hungry?’ She said she was. He took her inside and bought her some food and drink. I’ve learned a lot from him. I used to be an ornery little s**t. My heart got softer after seeing some of the stuff he did. He is not only my best bud; he is a hell of a role model.”

SCOTT SANDERS (friend): “Love, more than anything, was his greatest strength. That’s one of the things I learned from Pat. You have to love your players. If you have their best interest at heart, they will go to war with you. You ask any of his kids, they knew Coach Casey loved them and cared for them and wanted what is best for their lives and careers.”

DAN SPENCER (served as an assistant coach on Casey’s OSU staff from 1997-2007: “With his personality, there was no wiggle. You might lose 3-2 at Stanford on Friday night and think you did all right, but it was win or lose with Case. There were no moral victories. That was a good thing for me. As hard as that was, I know the players appreciated that. Not in the moment, but down the road. When those things started turning into 3-2 victories for the Beavers, then you understood the whole deal.

“We were in Omaha in ’07. Joe Patterson was rolling on the mound in one of the North Carolina games. I was sitting in the dugout next to Case. He looked at me and said, ‘What are you doing? You’re not giving signs.’ I was letting Mitch (Canham) call the game. The whole year, it was his game, at least until we got baserunners. I said, ‘Joe doesn’t need me. He’s rolling.’ He said, ‘Spence, I don’t know if I’m comfortable with that.’ So I went out to the mound to talk to Joe and Mitch. I told them, ‘Case is on my ass. I’m going to flash some numbers. Don’t pay any attention. You guys just keep doing what you’re doing. Just keep getting ‘em out.’ And it worked.”

AD RUTSCHMAN (At 92 years old, retired and living in McMinnville. The former Linfield football and baseball coach is a member of seven sports halls of fame. His grandson, Adley Rutschman, was Most Outstanding Player of the 2018 College World Series under Casey): “Pat is one of the great leaders in my lifetime. I’d like to see him be governor of the state of Oregon. I have told him that. He has the ability to raise everybody up around him.

“One of the things I like so much about him is, what you see is what you get. He has a strong value system. People need that. It gives them direction. It helps them make decisions. That’s what our country is lacking right now — good people. If he is in any leadership position, everything is going to be better. He is a great problem-solver. He can take something, dissect it and make a good decision. He is also a principled person. Things are right in his mind, or they’re wrong.

“He makes ballplayers better, but more importantly, he makes people better. People coming out of his program are going to be better people than when they went in. On top of that, they will be better ballplayers. He is going to test you, but if you stay in his program, you will benefit. That is maybe the most important thing.”

FRANK WAKAYAMA (played on Casey’s first George Fox team): “When you talk about ethics, morals and integrity, Pat is the one I think of. He has been there for me through some dark times. I can call him up today and he is there for me. I can’t say enough about him as a friend, a coach, a mentor, a leader.

“As a coach, I never saw anybody work as hard as him. He would challenge you. He expected effort from players, and got it. Some people didn’t make it. But the ones who bought it, they’d run through the wall for him. When people ask, ‘Who do you look up to?’ Pat’s name is the first that comes to mind.”

► ◄

In June of 2023, Casey retired his position as senior associate athletic director and special assistant to athletic director Scott Barnes. That position was OK and drew a nice salary, but it is coaching that he misses.

“I miss the faces of those guys 18 to 21 years old,” he says. “Even the bumps and the bruises as much as the good times. You don’t realize how much enthusiasm and energy and life they give you when you are around there all the time. They are young. Maybe that’s why I didn’t appreciate it as much when I started coaching, because I was young myself.

“I am so grateful for the time I had in the dugout with those guys. I wish I were as wise when I started as when I finished. I wish I’d had more patience. Sometimes the game is the teacher. That’s the way it is. It brings you back to wishing that you were still around that kind of motivation all the time.

“I had an opportunity to work with really good people. Not just players, but our trainers, our weight training people, academic people, managers, coaches. I don’t miss the recruiting, and I am glad I didn’t have to worry about the stuff coaches face now with the NIL and transfer portal. I don’t know if I would do very well with that. I don’t want to be in a money game based on where kids can get the best financial deal. You don’t have to develop a player where you can go out and buy who you want.”

Casey doesn’t regret the decision to retire from coaching.

“I put myself in a situation where I didn’t want to let people down,” he says. “The standards we held ourselves to were so high. I could have made things easier on myself. But I didn’t know how to do it any other way.”

In 2020, Casey started the Share Our Abundant Resources Foundation (Soar4: website soarvision.org), a non-profit designed to improve lives of those who need assistance with food, shelter, medical and educational opportunities.

“It’s a challenge,” he says. “We’ve done some good things; we want to do bigger and better things.”

Casey is helping Canham raise funds for a $6 million hitting facility that has begun construction beyond centerfield at Goss.

He is not sure what the future holds. Is he bored?

“Kinda,” Susan says. “He thinks he’s not. There is a little bit of boredom, and he has to learn to deal with it.”

“Dad doesn’t have any hobbies,” Brett says. “Every day I go over to their house, he is building a fence or a shed.”

“I built a shop out back,” Casey says with a laugh. “I’m running out of ideas here.”

He thinks he’d like to help out coaching, maybe at a local high school or college.

“I would love to be involved from the standpoint of really helping develop players,” he says. “Maybe as a hitting analyst or a third assistant somewhere. I’d like to do something that excites me. It could even be a different sport than baseball.

“I want to stay in Corvallis. It’s a comfortable place for Jon. We like living here. All our family is around here.

“Sports energizes me. I have been blessed with the ability to deliver a message to young kids that there’s something out there for you. I owe something to myself and whoever I can help. If I’m supposed to be doing something, I should be doing it.”

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.