Freddie Boyd was ‘awesome, a leader by example’ at Oregon State

It has been a rough week for loss in the local sports world. To wit:

• Freddie Boyd was a star guard at Oregon State from 1969-72, an All-American and All-Pac-8 selection as a senior. Boyd died from cancer on Sunday at age 73 in Bakersfield, Calif.

Boyd played for Paul Valenti as a sophomore and for Ralph Miller as a junior and senior. The Pac-8 was stocked with standout guards during that time, including UCLA’s Henry Bibby, Southern Cal’s Gus Williams and Paul Westphal, Washington’s Louie Nelson and Charles Dudley and Stanford’s Claude Terry. I thought Boyd — who would be taken with the fifth pick by Philadelphia in the 1972 NBA draft — was as good or better than any of them.

“Freddie was awful fast, awful quick, and he could shoot it,” says Jimmy Anderson, an assistant coach during Boyd’s time as a player in Corvallis. “He had a complete game.”

Sophomore Ron Jones started in the backcourt with Boyd during most of his senior season.

“Lightning quick — the quickest player I ever played with or against,” Jones says. “A lot of times, Ralph would have me guard the point guard so Freddie wouldn’t get tired. We played some one-on-one and he knew he could get by me, but he’d shoot only jump shots. Even though I knew what he was going to do, I couldn’t stop him. He was a great teammate, a fun-loving guy. He knew he was good, but he didn’t wear his celebrity on his sleeve.”

Jim Cave was a reserve guard who often guarded Boyd in practice that season.

“Freddie would just keep going up and laying it in over me,” Cave says. “He was at a different level. His quickness and strength were awesome. He was a quiet guy, a leader by example, and inclusive with everybody on the team. It’s too early for him to leave us.”

I remember something else about Freddie, observing the situation through my high school years. The Black Student Union walk-out occurred in March 1969, just at the end of Boyd’s freshman season. Many African American students, including basketball players Dave Moore and Brady Stewart, left school. Boyd hung around, staying in an extra room at the Corvallis home of OSU assistant coach Bill Harper until things settled down.

The teammate who knew Freddie best was Billy Nickleberry, a 5-8 jumping jack from Jefferson High and a member of the PIL Hall of Fame. They were starting guards together — and the only black players — as sophomores on a 1969-70 team featuring seniors Vic Bartolome, Gary Freeman and Vince Fritz. Boyd and Nickleberry played together at OSU for three seasons. Billy wasn’t a great shooter, but man could he jump for a little guy, and he was quick as a water bug up and down the court.

Billy Nickleberry, who played with Boyd at Oregon State, says he respected his teammate “as an athlete and as a person (courtesy Billy Nickleberry)

“Freddie and I were very close at Oregon State,” says Nickleberry, 75, retired and living with wife Virginia in Highland Ranch, Colo. “We ran around with each other. We did a lot of things together.”

Five days before Boyd died, Nickleberry called him to check on his condition.

“I had been told Freddie was probably not long for the world,” Nickleberry says. “We talked for 42 minutes. We laughed and laughed, and he actually sounded pretty good.”

Nickleberry came to Oregon State in 1966 during a time when not many black players had played basketball at the school. Charlie White had been the first black recruit two years earlier. Paul Valenti had taken over for Slats Gill as head coach, and Anderson and Harper were his assistants.

“Jimmy did most of the recruiting of me,” Billy says. “My parents absolutely loved Paul, Jimmy and Bill. They were the ones who got me to Oregon State.”

Billy played on the Rook team in 1966-67, then got drafted into the Army.

“I was in ROTC, and you weren’t supposed to be able to be drafted,” Nickleberry says. “Paul and Jimmy made sure I got in (ROTC). But when the draft board contacted Oregon State’s ROTC to ask if I was enrolled, (the ROTC representative) said no. I was told later that the guy misunderstood ‘Nickleberry’ and thought it started with a ‘K.’ ”

Nickleberry’s first orders were to go to Louisiana for advanced infantry training, but Valenti — a Bay Area native — pulled some strings to get him stationed at the Presidio in San Francisco. There he spent a year and a half and played on the All-Army basketball team.

When Nickleberry returned to OSU as a sophomore in 1969, Boyd was on the scene, he too a sophomore.

“Freddie was incredible,” Nickleberry says. “The guy could play basketball! I wasn’t nearly the player he was.”

Freddie Boyd was a three-year starter at Oregon State, an All-American and All-Pac-8 selection as a senior in 1971-72 (courtesy OSU sports communications)

During their recent talk, “Freddie and I reminisced about our time at Oregon State,” Billy says.

“We talked a lot about Paul and Jimmy, what wonderful men they were, and we agreed that Oregon State was a really good school for us.”

Boyd told Nickleberry that he had attended an NBA predraft camp with many of the nation’s star college players, including Bibby.

“He said they were telling him about all the free stuff they got at the school, which was all illegal at the time,” Nickleberry says. “They were shocked he wasn’t getting anything free at Oregon State. None of us were. Freddie didn’t even have a really good winter coat. He had to wait until his mother could save up to buy him a coat.

“But we agreed that was one of the things we liked about Oregon State, that made us better people. We weren’t expecting something for nothing. Paul and Jimmy and Bill treated us just like they treated anybody else. You earned what you got. We weren’t getting anything free. That’s wasn’t what life was about. Be honest, work hard and earn what you get.

“We went to a school that had integrity, fairness. Freddie said, ‘You know, Nick, we didn’t get the free stuff, but look at us. We’re better people for it.’ And I agree. He was really happy he’d gone to Oregon State. He loved his time there. We had a great experience with our coaches — Paul, Jimmy, Bill and then Ralph. If you needed to talk or something to eat, those guys would take you in their house and take care of you. You were always welcome.”

Nickleberry said they talked about the black walkout in ’69. Nickleberry had been in the Army at the time.

“He said the Black Student Union wanted him to lead the walkout,” Billy says. “They wanted him to be the speaker and denounce Oregon State and its practices. Freddie said he wasn’t going to do that. He hadn’t experienced anything bad with Paul, Jimmy and Bill in the basketball program. He didn’t want to denounce the football program, which he had nothing to do with. Had I been there, I’m not sure I’d have done it, either.”

The late ‘60s and early ‘70s was a turbulent time on college campuses, even at a more conservative school such as Oregon State.

“A lot of people were doing things,” Nickleberry says. “A lot of folks on campus smoked weed. We were both offered it at parties. We said no. He wouldn’t do anything like that. He didn’t smoke. I don’t ever remember him drinking. Freddie stayed pretty much to himself. He had a small group of people he hung out with. We did things together, but he was kind of a homebody.

“Freddie was a person who was loyal to his friends. If he liked you, you didn’t have to worry about anything. He was going to treat you like he wanted you to treat him. Freddie wasn’t going to go out and do anything illegal. He believed in being honest. I respected him as an athlete and as a person. I’m glad I got talk to him one last time.”

Nickleberry stayed at Oregon State as a grad assistant in 1972-73 under Miller.

“I helped recruit Lonnie Shelton,” he says. “I drove A.C. Green down from Portland for a visit.”

Nickleberry lived in Portland for many years after graduation. He spent 13 years at Portland General Electric, then worked for the state in a variety of capacities, retiring in 2004. Nickleberry moved to Arizona and worked for the city of Phoenix for 13 years. Billy and his wife of 36 years, Virginia, have lived in Colorado since 2017.

Boyd was named to the NBA All-Rookie team in 1972-73, averaging 10.5 points and 3.7 assists on a 76ers team that achieved the worst record in league history — 9-73. A knee injury shortened his career to six seasons, and he was done at 27. Many years later, when he served as head coach of the Beavers, Anderson hired him as an assistant. They had a falling out and, after three years on the staff, Anderson let Boyd go.

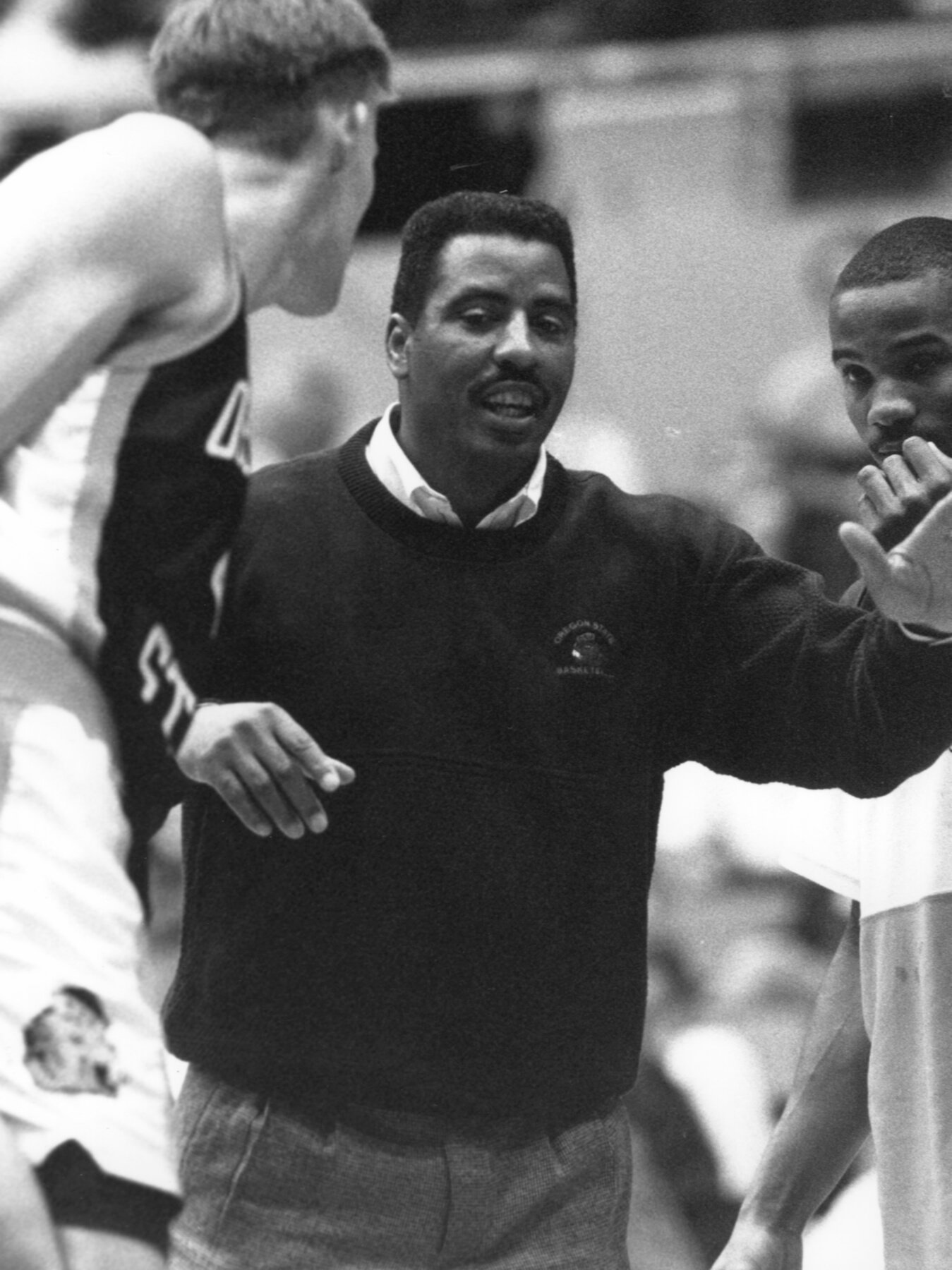

Boyd served three seasons as an assistant coach under Jimmy Anderson (courtesy OSU sports communications)

“I liked Freddie, but I don’t think he liked me very well, at least at the end,” Anderson says. “I don’t bad talk about people. I’ll say a prayer for him and let it go.”

• Passing away at the age of 81 in San Tan Valley, Ariz., was Lynn Eves, a standout sprinter at Oregon State from the early 1960s. Eves posted career bests of 9.6 in the 100, 21.0 in the 220 — a school record at the time — and 46.7 in the 440, the event in which he was a two-time Northern Division champion. A native of Victoria, B.C., he represented Canada in the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome as an 18-year-old.

Eves was my insurance rep for many years in Portland and a terrific guy.

Terry Dischinger (right, with local scribe) was a popular member of the Portland-area community for a half-century

• Terry Dischinger has died at 82. The 6-7 forward spent the final season of his nine-year NBA career with the Trail Blazers, retiring in 1973. He averaged 6.1 points and 3.0 rebounds in 15 minutes a game for the 21-61 Blazers under Coach Jack McCloskey.

Dischinger was a member of the 1960 U.S. Olympic basketball team that won gold at Rome. At 19 and finishing his sophomore year at Purdue, he was the youngest member of a team that included future Naismith Hall of Famers Oscar Robertson, Jerry West and Jerry Lucas.

Terry had an unusual and productive rookie season with the NBA’s Chicago Zephyrs in 1962-63. He averaged 25.5 points and 8.0 rebounds in 57 games, winning Rookie of the Year honors despite missing 23 games under an unusual agreement with the team. Dischinger was completing his studies in chemical engineering at Purdue and got permission to miss some games while attending school.

Dischinger would go on to make the All-Star Game in each of the first three NBA seasons. After retirement, he served nearly 40 years as an orthodontist in Lake Oswego. Terry lived his final years at The Springs at Lake Oswego, where Bill Schonely spent his final days. Every time I saw Terry, he would greet me with a smile and a handshake and we’d chat for a minute. A humble and very nice man.

• Last weekend was also the end for another Portland sports fixture — Claudia’s Sports Pub closed its doors after 65 years in business. Claudia’s, on Southeast Hawthorne Blvd., was the city’s original sports bar, established in 1958 by restaurateur Gene Spathas. It remained a family-owned business, taken over by Gene’s youngest son, Marty, who ran the place for the last 35 years. It was a great place to grab a brew, eat a “Boss Burger” and watch a ballgame.

Last Saturday’s grand finale party drew an overflow crowd of regulars, well-wishers and friends of the Spathas family, a nostalgic goodbye to another Portland institution biting the dust.

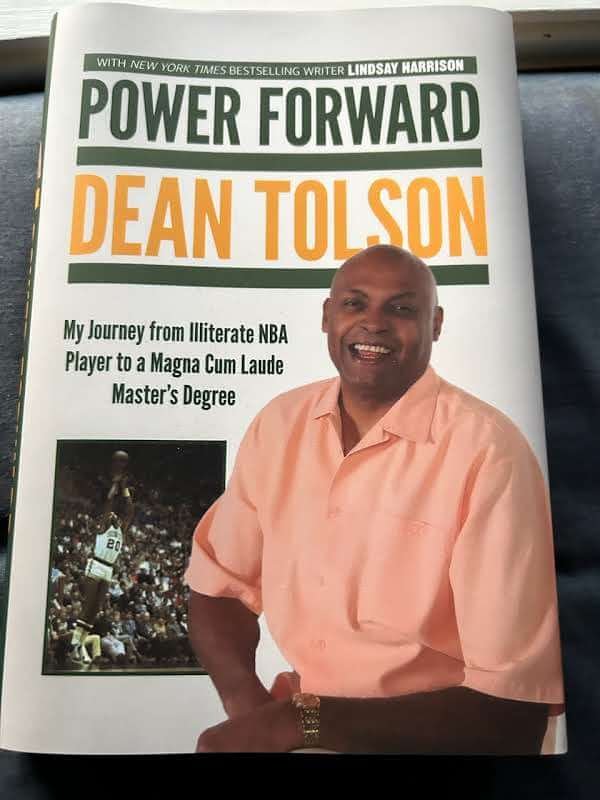

• I’m on a couple of publicists’ lists, and occasionally a sports book will be offered that I choose to review. One of them was a recently released autobiography titled, “Power Forward: My Journey from Illiterate NBA Player to a Magna Cum Laude Master’s Degree” (with Lindsay Harrison, Lyons Press).

The author is Dean Tolson, who played parts of three seasons — 80 games total — with the Seattle SuperSonics from 1974-78. He later played pro ball internationally for 11 years.

Tolson’s is a compelling story. The Kansas City, Mo., native is the product of a broken home. His father left the family when Dean was five. His mother raised five children by herself in the projects except for a five-year period in which three of the kids — Dean included — lived in an orphanage.

Tolson says he was illiterate until his 30s. Remarkably, he was passed through from one grade to another (except fifth: he took that twice) and then through college at Arkansas without being able to read or write. “As long as I could put a basketball through a hoop and win games, I was welcome,” he writes.

After his playing career ended, Tolson returned to Arkansas and, with the help of athletic director and former football coach Frank Broyles, got his undergraduate degree in education at age 36. With the aid of a tutor, he learned to read and write. Many years later, Tolson returned again and, in 2007 at age 55, earned his master’s degree — with magna cum laude status. In a ceremony in Fayetteville, his No. 54 was retired, and a “Dean Tolson Comeback Scholarship Award” was established.

That those achievements were considerable under the circumstances are undeniable. Good for Tolson.

There is a local angle to the story. His coach at Arkansas from 1971-74 was Lanny Van Eman, a fact I didn’t know until I opened the book. I have known Lanny for many years. He was an assistant coach at Oregon State under Ralph Miller from 1980-88. Van Eman played for Miller at Wichita State and coached with him there and at Iowa before joining him at OSU.

Lanny was named Southwest Conference Coach of the Year in 1972-73 but had losing records his other three seasons at Arkansas and resigned in 1974. His resume includes later stints as an assistant coach with the Boston Celtics and Dallas Mavericks. Now 84, he is retired and living in Tustin, Calif.

In his book, Tolson says Van Eman cheated to get him into Arkansas. Tolson’s sub-2.0 high school grade-point average wasn’t close to the school’s qualifying standards. Tolson says he signed a letter of intent to go to Xavier and play under Coach Bob Hopkins — who would later serve as an assistant with the Sonics while he was there. But he wound up in Arkansas, and writes that Van Eman arranged for him to take his ACT and SAT tests the summer before his freshman year at Rockhurst College in KC.

Tolson tells the story of Van Eman picking him up at his home in Kansas City with a “white boy about 4-11” in the backseat of the car. “He reminded me of Poindexter, the character in the ‘Felix the Cat’ cartoons,” Tolson writes.

A couple of blocks down the road, writes Tolson, Van Eman nods toward Poindexter and tells Tolson, “Today, this young man is going to be Dean Tolson. … he’s the one who will be taking your test this morning.”

Tolson claims he protested, drawing this response from Van Eman: “Look, you can take the test, but you can’t pass the test. So you better think hard and fast, or you won’t be attending school anywhere, and you’ll never play basketball again in your life.”

Tolson agreed, and Van Eman revealed a plan he had arranged for the diminutive stand-in to take the test. He passed, and Tolson gained admission, leading to four seasons at Arkansas in which he dodged classes but somehow managed to stay eligible. Tolson claims Van Eman and his assistants help ward off professors who might have endangered Tolson’s eligibility. Tolson left school after his senior basketball season with a 1.43 GPA.

On the court, it was all good. As a senior, Tolson averaged 22.5 points and 13.2 rebounds, the latter a single-season school record. His career averages were 18.3 and 11.7, so there was a lot of value to his play to counteract the drama he created off the court — and wrote about at length.

I called Van Eman, who hasn’t read the book but has heard most of Tolson’s allegations before. He danced around them and switched subjects several times, starting with, “that does not ring a bell” and “it’s not really true.”

When I told Lanny that didn’t seem like a firm denial, and asked directly if Tolson’s account of Van Eman’s involvement in his entrance testing was accurate, he eventually countered with, “It’s complete fabrication.”

After he had been admitted at Arkansas, writes Tolson, he spoke with Hopkins, who “told me that he would have gotten me academic help rather than let me cheat my way into Xavier.”

There’s no doubt that Tolson was a handful for Van Eman, who says “he required a lot of managing … he was a challenge. But Dean had a remarkable career in a certain kind of way at Arkansas. He was not surrounded by a lot of other good players.”

Van Eman tells a story about attending a coaches convention in Nashville in which Bill Russell spoke. Van Eman introduced himself and told him he had coached Tolson, who later played for Russell in Seattle.

“Bill looked me in the eye and said, ‘Coach, I wouldn’t admit that if I were you,’ ” Van Eman says.

Before his senior season, Tolson had spent some time doing Army National Guard training in Lawton, Okla. Van Eman recalls an incident after Tolson returned before a practice in December of 1973.

“Two guys in suits come into the gym and tell me they’d like to talk to Dean,” Van Eman says. “They flash badges — they were federal people. Apparently while in Oklahoma, Dean had run up several thousand dollars of telephone bills. They finally caught up with him.”

Van Eman says the feds took Tolson to Lawton for questioning.

“He was gone for nine days,” Van Eman says. “I didn’t know anything except he was gone, and I didn’t know if he was ever coming back. I lied to the media and said I was suspending him for grades. I think his mother had to go to Lawton to get him out.”

I’m not sure if Tolson — who evidently for many years made a living through motivational speaking — is telling the truth, or Van Eman. I do find it hard to believe that Lanny coached Tolson for three varsity seasons and was unaware his star was illiterate.

And the entrance tests story? I guess the only way to know for sure is to find Poindexter.

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.