For Mac Wilkins, track and field has been a life’s passion. A very good one at that

Mac Wilkins is contemplating whether he will attend the World Track & Field Championships, which run Friday through July 24 at Eugene’s Hayward Field.

Qualifying for the men’s discus is Sunday. The finals are Tuesday. Wilkins, a four-time Olympian and the 1976 Olympic discus champion would like to be there.

“I hope to be in Eugene,” Wilkins told me Thursday in a phone conversation from his home in San Diego. “But I haven’t gotten everything squared away. I have a lot of fluidity in the things I’m attending to.”

Mac’s wife of 37 years, Fran, has a compromised immune system.

“The new variant of Covid is growing faster than people on the street realize,” the Beaverton High and University of Oregon grad said. “I don’t want to bring something home. Some of it is that; some of it is other stuff going on. And I have no ties with athletes I worked with recently.”

Depends on what you consider “recently.” From 2013-16, Wilkins, now 71, served as men’s throws coach at the USA Track & Field Performance Training Center in Chula Vista, Calif. His job was to train potential Olympians.

One of those was Andrew Evans, the U.S. Olympic trials champion who is ranked No. 9 in the world. Wilkins also spent time working with Sam Mattis, ranked sixth in the world with the top U.S. performance in 2022, and Ryan Crouser, the Barlow High grad who is world record-holder and two-time defending Olympic champion in the shot put.

Wilkins should be in Eugene to watch these great athletes perform in the first-ever World Championships on American soil.

He should be there for another reason, too.

Wilkins is the most accomplished thrower in Oregon’s long and decorated track and field history. During the men’s discus competition, he should be introduced to the crowd and treated with a long standing ovation.

They called him “Multiple Mac” during his days with the Ducks. He is arguably the greatest four-event thrower in history, with bests of 232-5 3/4 in the discus, 69-1 1/4 in the shot, 208-10 in the hammer and 257-4 in the javelin through 20 years of college and international competition.

Javelin was probably his natural event, but he suffered an elbow injury as a sophomore at Oregon in 1971 — three years before Tommy John surgery was invented. The javelin was too hard on the elbow to continue. Once he left Oregon, Wilkins concentrated on the discus. He was ranked No. 1 in the U.S. eight times, including five years in a row (1976-80), claiming the Olympic title in Montreal in ’76. He made the U.S. Olympic team in 1980 but missed out because of the U.S. boycott of the Moscow Games. He earned silver at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles and was fifth at Seoul in 1988 at age 37.

Wilkins set four world records in the course of two weeks in 1976, was the first thrower to reach 70 meters (229-8), held the world mark from 1976-78 and is a member of the USATF Hall of Fame.

Mac competed in the first World Championships at Helsinki in 1983, serving as the U.S. flag bearer for the opening ceremonies.

“I was thrilled for the opportunity,” he said. “I was well into my career and proud to be an American. But it was a horrible competition for me, one of those that every athlete hopes won’t happen. I finished 10th.”

Wilkins retired from competition in 1989 and eventually wound up back in Portland. In 2005, he began an eight-year run as head track and field coach at Concordia University, transforming the program into a national small-college powerhouse. Wilkins’ athletes won 25 individual NAIA throws titles, and his legacy includes completion of the Concordia Throws Center in 2008.

The throws center was a labor of love for Wilkins, who built the facility from scratch. I remember visiting it on land by Portland International Airport before it was finished. Mac was proud that he had enabled many youngsters to excel in the event he loved.

In 2013, Wilkins left for southern California for his job with USA Track & Field, where he worked with some of the nation’s premier throwers. For two years, he trained Evans, who competed in the 2016 Games at Rio de Janeiro and is now 31.

“Being the national champion is huge for Andrew,” Wilkins said, “but he needs to throw farther. He knows that. He is probably five meters away from being competitive for a podium spot in Eugene.”

Wilkins worked a few times with Mattis, 28.

“A talented athlete,” Wilkins said. “I don’t think he has gotten his full measure out yet. Maybe he’ll never get there, but I think he can improve.”

Wilkins goes way back with Ryan Crouser’s father, Mitch, who was fourth in the discus at the 1984 Olympic trials. Mac first observed the prodigy when he was age 10.

“I’d get together with them and watch Ryan throw and make some comments,” Wilkins said. “Mitch understands technique, and Ryan is smart, intuitive and logical, and he understands the physics of the human body. What he has done with his career is the way you want to do it.

“I can’t really say I coached him, though I was his official coach (in Chula Vista) for the 10 weeks leading up to Rio in 2016. In reality, he is coached by himself and his dad. I was there at Rio and I was very proud. I was just glad I didn’t get in his way and screw things up.”

Wilkins added another thought about Ryan: “I think he could be doing similar things in the discus if he decided to do that, but you can make four to five times more money throwing the shot. Discus is not a big attraction.”

Wilkins’ stint with USA Track & Field ended following the 2016 Olympic Games. Since then, he has worked with international clients. In 2018 and ’19, Mac served as men’s discus coach for the People’s Republic of China. It meant some trips to Beijing.

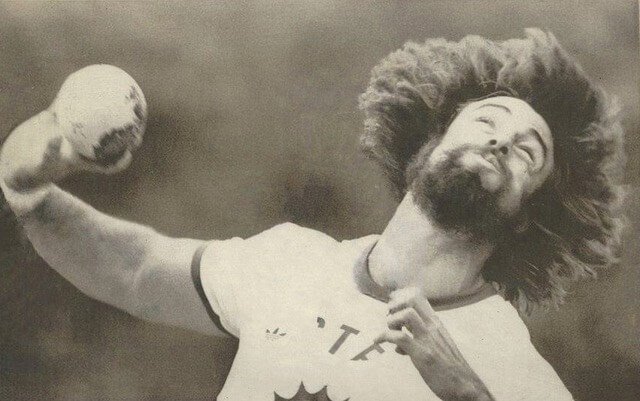

Mac Wilkins today looks younger than his 71 years. He carries 220 pounds on his 6-4 frame, down 30 to 40 pounds from his peak as an Olympic athlete (courtesy Mac Wilkins)

“They have their top athletes train all around the world,” he said. “The sense is they’re probably better off training outside of China. For the foreign coaches who come work with the athletes, the feeling is mutual.

‘I can deal with the cultural differences, but the burning of the eyes and the raspy throats (from air pollution) while in Beijing — that was a difficult thing. I was there for several visits, each time a week to three weeks. But most of the time, the athletes were in Chula Vista with me. And that was good. I enjoyed doing it.”

The Chinese Athletic Association didn’t set its goals high.

“The biggest country in the world, and their goal for the Paris Olympics (in 2024) is to get somebody good enough to qualify to compete,” Wilkins said. “That’s a sad statement for a country that size, especially one that has had athletes like Yao Ming. You’d think they could get discus throwers who are the right body type. Unfortunately, not. Their top people are a little better than average collegiate throwers. They have improved, but if you want to win medals, you have to have horses.

“The goal for my (Chinese) discus group would have been to win the Asian Games in September. Covid postponed the Games to 2023. My No. 1 guy’s best result is 201 (feet). To qualify to compete in Eugene, you have to be among the world’s top 32, or meet the qualifying standard of 216-6.”

Wilkins also trained Iran’s Ehsan Hadadi, the silver medalist in the 2012 Olympic Games. Hadadi, 37, has a back injury and will not be competing in Eugene.

Has anybody questioned Wilkins’ patriotism in working with athletes from China and Iran?

“Maybe they haven’t found out yet,” he said with a chuckle. “I’m not wearing my China or Iran T-shirt when I go grocery shopping.

“In dealing with the athletes, and to most extent the administration of the sport, it’s completely separate. Dealing with the politics is a nuisance to be dealt with like the weather. We’re all about performing better and improving, and the Chinese Athletic Association has a policy of hiring foreign coaches to that.”

As an athlete, Wilkins developed a close relationship with 1976 silver medalist Wolfgang Schmidt before East Germany broke away from Communist rule. Wilkins has always believed in fair and open competition. Russia, however, has never been about that.

“In sports, my view of Russia is that it’s the only country where the culture is playing by different rules,” Wilkins said. “They don’t have the Western concept of fair play on an athletic field. From my experience in the ‘70s and ‘80s, it was, ‘What is going on here? This is goofy. Are you trying to screw things up?’ ”

Wilkins first noticed improprieties in judging and scoring in 1973 when he twice visited Russia for the World University Games and the U.S.-Russia dual meet. The Americans boycotted Moscow in 1980, but Wilkins got a first-hand report from some who were there. What was then the Soviet Union won the most medals with 41, followed by East Germany with 29 and Great Britain with 10.

“They had to bring in international officials because there were so many complaints about Russian officials in track and field,” Wilkins said. “They were blatantly cheating. Soviets won all four throwing events in ’80. In the discus, the longest throw was by the Cuban, Luis Delis, but he got third place because of mismarking the throws.

“Wind can greatly affect the javelin. They had giant doors at the end of the stadium. They would open them up for a favorable wind for the Russian javelin throwers and close them for everybody else.”

Wilkins doesn’t hold the athletes accountable.

“It’s the officials,” he said, “and it all comes from the top.”

In those days, that was Soviet leaders such as Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko. Today, it is Vladimir Putin. In Wilkins’ mind, Putin’s onslaught in Ukraine rightly puts Russian athletes on the sidelines at the World Championships.

“Sure,” he said. “Kick them out. There’s no reason why they should be here. Sorry, if you’re an athlete from that country, it’s not where you want to be if you want to compete. They do not deserve to be competing on the international stage because of their government. The war flows from the same place as the cheating on the athletic field.”

Over the years, Americans have had little success in the men’s discus in the World Championships, winning only three medals — Anthony Washington, gold in 1999; John Powell, silver in 1987, and Mason Finley, bronze in 2017. Why so little success?

“The U.S. was strong in the discus through the ‘70s,” Wilkins said. “After that, the rest of the world got serious in their endeavors into the event and left the U.S. behind.”

Many of those big, strong and athletic enough in the U.S. to win Olympic medals go to the NFL.

“That has hurt,” Wilkins said. “The top guys in the world right now are Sweden’s Daniel Stahl, who is 6-7, and Slovenia’s Kristjan Ceh, who is 6-9. Tall people usually come with longer arms. You can create a whole lot more force, and it is going to go farther.”

Only three of the top 19 throwers in history have uncorked their personal bests since 2006. East Germany’s Jurgen Schult’s world record of 243-1 was set in 1986. Nobody has come close since Gerd Kanter of Estonia (2006) at 240-9. Why are the world’s throwers not getting better?

“There’s another metric that would indicate the opposite has happened,” Wilkins argued. “The discus is like a glider plane. The wind has a huge effect on it. Usually, there is no wind or a swirling wind in a large stadium. Eugene is a unique situation in that rarely can you get a good wind for a long discus throw, and usually it’s neutral or slightly negative. Comparing Eugene to another location, the same throw elsewhere will go two to five feet shorter in Eugene. You can see a 10- or 12-foot improvement because of an incredible wind, which happened when the world record was set in Germany.

“The top marks that win medals in the Olympics and World Championships have improved from the olden days. I am seeing it take 68 to 69 meters to win most of the major events (from 223-230 feet). I won the Olympics at Montreal at 67.50 (221-5). That result would not have won a medal today.”

Wilkins never tested positive for steroids or other performance-enhancing drugs, but plenty of competitors did through his years of competition, especially those from behind the Iron Curtain. Wilkins downplays its significance, though, and doesn’t believe today’s more extensive drug testing has made a big difference.

“It just means the guys today are not taking drugs,” he said. “The end result is one era to the other. You get guys throwing farther now than they were in the drug era — how is that? Everything gets better. Maybe (PEDs) wasn’t as much a factor as some people would think.

“Nobody has thrown the shot like the men are throwing it today. During my time at Chula Vista, they were tested. As an athlete today, you’re a little paranoid about what happens when you go out to eat, about some of the nutritional supplements you take. They might have a little something in them that’s not legal from the FDA point of view.”

Sadness came in 2020 when Concordia University closed its doors due to financial challenges. Nobody has been around to take care of the throws center since.

“I haven’t been by it since then, but I’ve heard that Dignity Village, which was across the street, has spilled over onto the field,” Wilkins said. “If they take care of the place, don’t let it turn to crap, it would be a great resource for athletes in the area. But homeless people probably have a higher need than athletes a place to throw.”

Too bad, Wilkins said.

“We ended up with something positive and unique,” he said. “Over the last few months, I had a half-dozen calls from around the world asking if they could work out there leading up to the Worlds.”

Wilkins has yet to visit the renovated Hayward Field. He has, of course, seen pictures.

“It’s the giant UFO that landed on campus,” he said, laughing. “It looks like they squeezed an 18-wheeler into a compact car parking lot. But I’m glad they did it. It’s quite exciting.”

Wilkins feels satisfied with what he accomplished as a track and field athlete.

“I didn’t really have any expectations,” he said. “In April 1969, after my senior year of basketball at Beaverton High, I remember being so excited when I got a recruiting letter to play basketball at Blue Mountain Community College. I took basketball recruiting trips to Linfield and Willlamette. That was pretty cool. I thought, ‘Maybe I could do something besides play intramural sports in college.’

“Then I got connected with (former UO track and field coach) Bill Bowerman. Going into my junior year at Oregon, I had no idea what it would lead to. I was trying to figure out how to keep my scholarship as a javelin thrower with a bad elbow..”

Wilkins never made a lot of money as a professional in his sport. After the 1976 Olympics, he had a $5,000 shoe deal with Adidas. The next year he switched to Nike, with whom he stayed until after the Olympics in 1988, when the shoe and apparel giant dropped him. His last “half-season” served up an endorsement deal with Reebok.

“Before the ’88 Games in Seoul, just for fun, I tried out a Ferrari,” Wilkins said. “I couldn’t fit into the driver’s seat. I didn’t win the gold medal, so I bought myself a set of golf clubs.”

Wilkins considered seeking a throws coaching job with a major university. He even sniffed around at his alma mater.

“I decided it’s a real grinder,” he said. “Your competition is not coaches at other schools competing with you for athletes. It’s your fellow assistant coaches competing for scholarship dollars for athletes in their events. It’s also about having success so you can move into another situation where you’re making $25,000 more than you were making. It didn’t seem like a good fit for me.”

So he went the small-college route, and worked with international athletes. And had fun with it.

“I’m OK if I don’t coach anymore,” he said. “I’m not addicted to it. I don’t have to be out there doing something with throwing. If the right opportunity comes up, I would probably say yes. But the barrier for the right opportunity is a little bit higher now than it was five, or certainly 10 or 15 years ago.”

Wilkins said he is keeping busy. He carries 220 pounds on his 6-4 frame, down from the 250-260 range while a discus competitor.

“I don’t know that I have a hobby,” he said. “I like to stay active and fit. Fran and I walk three miles or so four to five times a week. I lift weights four to five times a week.

“I still communicate with a lot of people in the throwing world. Like most people, I feel better when I’m engaged in doing something to help others. Right now I have a bit of a lull in that. I’m looking for the next opportunity to present itself.”

That will come soon enough. But before that, Mac, get to Eugene for the men’s discus competition. Wear a mask and stay outside when you can. Be smart.

And when they introduce you to the Hayward Field denizens, and they roar their appreciation for what you accomplished, take a bow. It is deserved.

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on Twitter.

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.