Final Four players return to Gill 60 years later — ‘We were pretty good’

CORVALLIS — There they were, together again, 60-plus years after joining forces to put Oregon State into college basketball’s Final Four.

Mel Counts and company paraded onto the Gill Coliseum floor during halftime of Oregon State’s 84-71 victory over Arizona State last Saturday, the same court where they put together one of the greatest seasons in program history.

The 7-foot Counts was the All-American and football star Terry Baker the orchestra leader, and the supporting cast filled roles admirably as the 1962-63 Beavers won the Western Regional and made it to the Final Four in Louisville.

Baker, at his winter home in Indian Wells, Calif., was unable to attend. Six players made it to Corvallis for a full Saturday of activity, including a luncheon, a chance to watch the Beavers’ game-day shootaround and the halftime presentation at Gill.

Counts, Steve Pauly, Frank Peters, Jim Kraus, Jim Jarvis and Rex Benner were on hand for the festivities, renewing friendships that have lasted more than six decades. All except Peters are in their early 80s — “The Flake” turns 80 in April — but all are in reasonably good health.

“It was a great weekend,” says Counts, 82, retired and living in Corvallis. “We were treated really well. It was a lot of fun to have everybody together again.”

Baker and reserves Gary Rossi, Dave Hayward and Tim Campbell didn’t make it for the reunion. Reserves Ray Torgerson, Grant Harter and Lynn Baxter — the latter the grandfather of Beaver football All-American Jordan Poyer — are deceased. So are head coach Slats Gill and assistant coach Paul Valenti.

Jimmy Anderson was in attendance. Ironically, Anderson played or coached at Oregon State from 1956-95 with the exception of the 1962-63 campaign, when he left for one year to teach and coach at Newberg High.

But he served as freshman coach for many of this group of Beavers.

I sat down with each player in attendance — and spoke with Baker via telephone — to relive memories of that special year.

► ◄

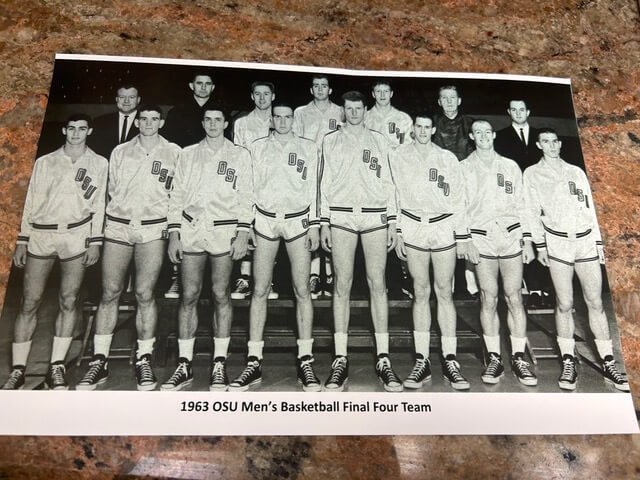

The 1962-63 Oregon State basketball team. Front row from left, Gary Rossi, Ray Torgerson, Steve Pauly, Jim Kraus, Mel Counts, Tim Campbell, Terry Baker, Jim Jarvis. Back row from left, trainer Bill Robertson, assistant coach Paul Valenti, Dave Hayward, Rex Banner, Frank Peters, coach Slats Gill, manager Corky Smith. (Missing: Lynn Baxter, Grant Harter)

Gill was already a legend — heck, he already had the coliseum named after him — and in the 35th of his 36 seasons as Oregon State’s head coach, dating to the 1928-29 campaign. Before that, he was a three-time All-Pacific Coast selection as a player and an All-American as a senior in 1923-24. Gill won 599 games and is a member of the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

Counts was the centerpiece, a junior center who would be a member of the 1964 U.S. Olympic team that would win the gold medal at Tokyo. As a sophomore, Counts had joined with 6-8 senior Jay Carty to lead Oregon State to a 24-5 record and an Elite Eight appearance in the NCAA Tournament.

Gill, Valenti and Anderson began recruiting Counts when he was a sophomore at Marshfield High. He got dozens of scholarship offers, but picked Oregon State quickly.

“After getting to know the coaches, that’s the only place I wanted to go,” Counts says. “I was convinced this was where I should be. I have no regrets. Four of the best years of my life were spent at Oregon State — not just athletically, but academically and socially.”

In 1962-63, Counts partnered with Baker, the football quarterback who would win the Heisman Trophy in early December, delaying the start of his senior basketball season. Steve Pauly, a 6-4 senior, and Frank Peters, a 6-2 sophomore, were starters along with 6-7 sophomore Jim Kraus. Six-foot sophomore guard Jim Jarvis was the sixth man.

The 6-3 Baker joined the basketball team just before Christmas at the Kentucky Invitational, coming straight from Philadelphia, where his 99-yard run was the only score in the Beavers’ 6-0 Liberty Bowl win over Villanova.

Baker, a three-sport star at Portland’s Jefferson High, could have played football, basketball and baseball in college. He attended Oregon State on a basketball scholarship and didn’t play Rook football.

“Basketball was the most fun for me,” Baker says. “In football, you get beat up. College wasn’t as bad as high school, because the high school fields were so bad. Our field was muddy, and you’d get laid out in the mud and cold weather. In basketball, you’re in a nice warm gym. I liked that.”

The Beavers lost 70-65 to seventh-ranked West Virginia in their Kentucky Invitational opener to fall to 2-3 for the season. Then they ran off seven straight victories, finishing the run by beating Iowa in the finals of the Far West Classic.

“When Terry came back, he was the piece we were missing,” Counts says. “The team started gelling and working together.”

“Terry was good, but he was not a pretty basketball player,” Jarvis says. “He was strong, with a good first step. He’d hold you off, lean into you and get the shot off. He was encouraging to me, a senior to a sophomore. And you’re in awe — I mean, he’s the Heisman Trophy winner. Not every day you get an opportunity to play with somebody like that.”

Peters and Baker roomed together at the Phi Delta Theta fraternity.

“What a great guy,” Peters says. “Terry was a star but always so down to earth. The thing I couldn’t believe, he never studied and still got great grades. How does this happen?

“As the competition got better, he didn’t have the quickness of some of the guards nationally, but as a player, he was really good. He could do everything. He was deceptively fast. You saw that when he played quarterback. He ran away from those defensive backs in the open field.”

The Beavers were about as close a group as can be had at the college level. Ten of the 13 players were members of two fraternities. Baker, Peters and reserves Ray Torgerson and Gary Rossi were Phi Delts. Counts, Kraus, Jarvis, Benner and Baxter were affiliated with Beta Theta Pi.

“It was a great bunch of guys,” says Baker, 82 and retired after a long career as an attorney in Portland. “We had a lot of fun playing together. Most of us had been together for some time. I made some lasting friendships from that team. And there are a lot of interesting memories about our time together. I didn’t like the way the season ended, but the rest of it was great.”

Baker was probably closest with Pauly, a Beaverton High grad. They had played together in the Oregon Shrine High School football all-star game after their senior year. Baker had already committed to Oregon State. Pauly was undecided. Before Baker made his decision, they had taken a recruiting trip together to California and Stanford.

Terry relates another recruiting story.

“Pauly and I are in Corvallis before school has started,” Baker says. “It’s fraternity rush week. Washington was really after both of us. Steve told me Washington wanted him to visit that weekend. So I tell Slats that if Pauly goes to Seattle he may very well commit there. I told him, ‘Whoever talks to him last is going to get him.’ ”

Gill quickly arranged a meeting at the Phi Delt house — where Baker and Pauly were staying — that included football coach Tommy Prothro, Valenti and business/ticket manager Jim Barratt. Prothro was preparing his team for its season opener at Texas Tech the following Saturday.

“They sit us down and say, ‘OK, we’ve arranged for the two of you to go on a deep sea fishing trip at the coast,’ ” Baker says. “Pauly doesn’t say a word. So I tell them, ‘Steve doesn’t like to fish.’ I’m like his agent. They ask, ‘What would you guys like to do?’ I say, ‘Neither of us have been to Texas.’

“Prothro says, ‘All right, be at the airport at 6 a.m. the next morning.’ We flew to Lubbock with the team and had a great time. The next week, Steve enrolls in school at Oregon State.”

“Terry going to Oregon State was an incentive,” says Pauly, 83 and retired after a 50-year career as a dentist, living in Portland. “It was a real privilege to play with a guy like Terry. He was such a great athlete and he gave it 100 percent. Can’t get any better than the Heisman trophy, and he was a quarterback for us in basketball, too.

“Plus, I liked the tradition of Oregon State basketball. Track was up-and-coming under Sam Bell. He was quite a salesman, a go-getter. And I liked the school scholastically.”

Baker and Pauly have remained close through 65 years of friendship.

“I can’t say enough good things about him,” Baker says. “Any parent who has a boy should want him to grow up to be like Steve Pauly. He is an exceptional person.”

Gill mostly used six players, four of them with state-of-Oregon roots. Baker and Pauly were from the Portland area. Counts was from Marshfield, Jarvis from Roseburg.

“We were mostly Oregon kids all through the roster,” says Benner, a Grants Pass native. “You’re never going to see that again. Now schools go all across the country to get players. Then, kids wanted to stay home. Their parents wanted them close so they could watch them play.”

The 6-3 Benner became a three-year basketball letterman at OSU, but his career was ill-fated. He was a fine quarterback at Grants Pass High and was offered a football/basketball scholarship at Oregon.

“It was a tossup where I was going between Oregon and Oregon State,” Benner says. “I had a dorm reservation and was all set to go to Oregon before school started.

“But they gave seven basketball rides that year, and the catch was you had to make the varsity as a sophomore to keep the scholarship. At Oregon State, it was a four-year offer. And we had only three — myself, Mel and Lynn — in our recruiting class.”

The summer between his freshman and sophomore year, he suffered an injury that caused him to lose sight in one eye.

“Somebody threw a stick and it (impaled) my eye,” Benner says. “It severed my optic nerve and broke my cheekbone. They re-set the bone.”

Benner was fitted with a prosthetic eye. He played his three varsity seasons with only one eye. How much did that impact his performance?

“A lot,” Rex says. “It was an adjustment. It cuts down your peripheral vision. You have to move your head a lot more. But I don’t think it affected my shooting. I could still shoot as well as most of the guys.”

“He would have played a bigger role for us,” Counts says. “He was good-sized for a guard and an excellent shooter. Can you imagine the difference playing basketball with one eye instead of two? But Rex got the most out of what he had left. It’s astonishing that he accomplished what he did with one eye. After it happened, he didn’t mope around. He hung in there and gave it all he had.”

Benner had a long career as a high school teacher and basketball coach in Oregon, Northern California and Alaska. He is now retired and living in a community between Bend and La Pine.

“It’s a laid-back lifestyle there without the traffic,” Benner says. “It’s OK for me.”

► ◄

Kraus and Peters were from California. Kraus was from Los Altos in the South Bay Area. He picked Oregon State over an offer from USF.

“I wanted to get away from home and experience something new,” he says.

Kraus wound up starting parts of his three varsity seasons, focusing on defense and rebounding. He averaged 3.5 points and 3.4 rebounds in 70 games.

“It was a very good decision to go to Oregon State,” says Kraus, 80 and retired after a career as a landscape contractor and living in Fresno. “I enjoyed my entire time here, except for the rain. I didn’t enjoy that too much.”

Peters was from Anaheim, but he knew all about Oregon State. His father and uncle, George and Norm Peters, were stars on the Beavers’ transplanted Rose Bowl champions of 1942.

“But I didn’t want to come here,” says Frank, retired and living in Portland after a long career as a tavern owner and restaurateur. “Oregon State was my last choice. Baseball was my first sport. I wanted to go to a baseball school. I had offers from Arizona, Arizona State and Cal.”

But the rides were for basketball, with the idea he would play both sports.

“I asked my high school coach for advice on where to go,” Peters says. “He said, ‘find a big man and go to that school.’ I met Mel on my recruiting trip to Corvallis, and we played some pickup games together, and he was overwhelming. I went, ‘That’s the guy. This is the place.’ What a good decision. What my coach told me was one of the best pieces of advice I ever got.”

Peters was a two-year starter in basketball, averaging 11.1 points in 60 games for the Beavers. Scoring points wasn’t his first responsibility.

“Slats made it clear what I was supposed to do,” Peters says. “Terry was the engineer who put it all together and moved us around and got us shots. Mel was great — always so positive and friendly. He was easy to play with. Your job was to throw the ball into him and play defense. Slats would say, ‘You guards get first look at the basket, and then it goes to Mel.’ He could bail you out if they put good defense on you, because he could shoot. In today’s world, he would have really been something.”

Frank Peters and Jim Jarvis

Says Kraus: “Mel was the star, but he didn’t act like a star. He was humble — very humble. So was Jarvis, who became a star when we were seniors.”

Like Peters, Jarvis played baseball at Oregon State, too. His father, Curt, was his basketball coach at Roseburg High. Bill Harper, who had played and coached both baseball and basketball at OSU, was his baseball coach.

“I liked them both,” Jarvis says. “I might have been better to stick with baseball, but I loved basketball more. That’s what it came down to.”

Jarvis averaged 6.2 points as a sophomore, starting a few games but mostly coming off the bench.

“I got to play about as much as the starters,” says Jarvis, now 80 and living in Corvallis, retired after a career in coaching and selling real estate. “Terry was the lead guard, which was my position. It was a learning experience, and a good one.”

Jarvis would blossom into a star the next two seasons, averaging 21.1 points and earning All-America honors as a senior in 1964-65.

Oregon State had remarkable athletic ability on its 1962-63 squad, with a number of multi-sport athletes.

The 7-foot Counts, who averaged 21.3 points and 15.6 rebounds as a junior in 1962-63, is the only player from that team to make the NBA. Counts played 12 seasons, winning championships his first two years with the Boston Celtics and getting to the NBA Finals four times with the L.A. Lakers.

Baker, of course, was the nation’s premier football player as a senior. He was the No. 1 pick in the 1963 NFL draft, then had a disappointing three-year NFL career, plus one season in Canada.

Pauly was the national runner-up in the decathlon as a junior and champion as a senior.

Jarvis played two years in the ABA, winning a league title with the Pittsburgh Pipers, and also a season of Class A baseball, mostly with the Eugene Emeralds.

Peters played 10 years of minor league baseball, including six at the Triple-A level.

A standout on the 1962-63 Rooks team, Scott Eaton from Medford, became a three-year varsity starter for the basketball Beavers. He played one year of football at OSU in 1966, then spent five seasons as a starting defensive back for the New York Giants.

“We had some really good athletes,” Counts says. “Terry and Steve were two of the greatest athletes ever to come out of Oregon.”

► ◄

When I ask the players about Gill, I draw a variety of responses.

“I didn’t communicate a lot with Slats,” Kraus says. “He never said much to me. He was pretty rough on other guys. My senior year, I played for Valenti. I had more of a relationship with him than Slats. I played on the freshman team with Jarvis and Peters. We were 19-1. Jimmy Anderson was our coach. I don’t think Jimmy ever raised his voice. He was mellow — a nice person and a good coach.”

“Slats was a disciplinarian,” Benner says. “It was a regimented program. We were a little like robots.

‘Go here, go there, get it in to Mel’ — and Mel would shoot. That was our offense.”

“Slats was tough,” Pauly says. “You had to not let Slats get to you — don’t take it personally if he got on you. He was trying to make you a better player. Our team came together that year. On defense, you had your back covered by the big guy in the middle. And on offense, if all else fails, get it to Mel. We didn’t mind. He was a good player and a good man.”

“Playing for Slats was like being in prison, and he was the warden,” Peters quips. “His best quote was, ‘You’re here to play basketball. You can go to college anytime.’ That was the way it was. I was there for three years and never one time talked to a reporter. You were pretty well isolated to the gym and where you lived on campus.”

“I had played for my dad (in high school), who was perfect for me,” Jarvis says. “Not because he favored me, which he didn’t, but because he gave me one thing at a time to work on. It was a great way to learn the game. Playing for Slats, I had to make a lot of changes in style of play, but overall it made me a better player. It was tough for me emotionally to make that change, because he was really old-school. Hard-nosed defense was the emphasis. Share the ball, block out, help your teammate.”

Counts was the most effusive in praise of the veteran coach.

“He was one of a kind,” he says, “a great disciplinarian. He knew the psychology of people and how to motivate each person. You respected him. You feared going into his office. You knew you were in trouble if you had to go there. You’d be there from one to two hours and it would not be pleasant, but I had the highest regard and respect for Slats. I didn’t learn basketball until I came to Oregon State and played for Slats, Paul and Jimmy. Slats was a great coach.”

Baker grew close enough to Prothro that Tommy came to regard him as if he were a coach. Same with Gill.

“It was such a change going from Prothro to Slats. Playing for Slats was a real experience,” says Baker, who always called him “Slats.” (“With Prothro, it was always ‘Coach’ or ‘Coach Prothro.’ ”) “Slats was a disciplinarian — very much so — and somewhat set in his ways.

“As a sophomore, your first experience playing for him, you would invariably see his wrath. He would basically bait the younger players. His favorite one was during practice he would ask somebody, ‘What went wrong on that play?’ And when the player described what he thought went wrong, Slats would invariably ask, ‘Are you coaching this team, or am I?’ You learned not to say anything.”

Baker says he was “forever getting Pauly in trouble” with Gill. The Beavers’ final regular-season road game in 1963 was at Oregon.

“When they announced the starting lineup during pre-game introductions, it was something like, ‘From Jefferson High, 21 years old, at guard, Terry Baker,’ ” Baker says. “I run out and stand at the foul line. The next one is, ‘From Beaverton High, 22 years old, at forward, Steve Pauly.’

“Pauly gets out there and I say under my breath, ‘Geez, you’re really an old guy.’ Steve had this smile that can light up a room. He’s laughing. Slats sees this on the bench and he is furious. He can’t wait for the other three guys to get introduced. We get to the bench and he rips into Pauly and says he feels like benching him because he is not taking the game seriously. And it’s all my fault.”

Baker pauses, then continues:

“I guess we were pretty good. We were well-coached. Slats got the most out of us. Mel was so good. Nobody could stop him. Slats did a very good job getting us prepared. You didn’t slack off. We gave it damn near our best effort most every game.”

Gill would listen to his floor leader. The Beavers’ worst loss of the year was 96-69 at Stanford in early January.

“Afterwards, Slats got me to the side and said, ‘I think we need to shake up the lineup,’ ” Baker says. “I said, ‘Well Slats, the five of us who have been starting, we know what each other is doing. We’re really comfortable knowing and thinking what each of the other guys’ reaction is.’ So he thinks about it for a minute and said, ‘OK, well, maybe we won’t.’ And he didn’t.”

► ◄

Playing as an independent, Oregon State finished the regular season 19-7 and was given a first-round opponent, Seattle U., in what was a 25-team NCAA Tournament field, with seven teams getting opening-round byes. The Chieftains had beaten OSU 60-58 in Seattle in the season opener, but the Beavers got revenge with a 70-66 win at Eugene’s McArthur Court. Counts contributed 30 points and 13 rebounds to offset the 28-point output by Seattle star Eddie Miles.

Next up were the Western Regionals at Provo, Utah, with the University of San Francisco the opponent. Counts scored 22 points and Baker 21 as the Beavers got by the Dons 65-61. That set up a matchup with fourth-ranked Arizona State, which was to face UCLA in the nightcap.

After Oregon State’s win over USF, Baker — the team captain — approached Gill.

“I’d gotten to know Slats and his idiosyncrasies fairly well,” Baker says. “He had a lot of one-on-one meetings with me about stuff. After the USF game, I told him, ‘It would be nice to watch the next game.’

True to form, Slats said, ‘Oh, I never let my teams watch the team they’re playing in the next game. I don’t want them deciding how they’re going to play certain individuals and how they’d do things in the game.’

“So I said, ‘Well, Slats, if you just told the players to not think about how they’re going to play them, they would do what you told them to do, and we could watch the game.’ He thought about it for a minute and said, ‘OK, I’ll go along with that, but you can only watch a half.’ ”

Arizona State blew out UCLA 93-79, scoring an amazing 62 points in the first half.

“I’m shaking,” Baker says. “I’m thinking, ‘Do we have to play these guys tomorrow night?’ ”

The Sun Devils were heavily favored over the Beavers.

“We were real underdogs going into that game,” Jarvis says. “Nobody gave us a chance to win.”

“Jumpin’ Joe” Caldwell, a 6-5 junior who would be the No. 2 pick in the 1964 NBA draft, was the Devils’ star.

“We hadn’t had any scouting report on USF,” Peters says. “But we knew all about ASU and Caldwell. Slats took Pauly aside and said, ‘You’re going to guard ‘Jumpin’ Joe.’ ”

The Beavers led 43-38 at the half and broke it open in the second half to win going away at 83-65.

Counts — who was named MVP of the Regional — collected 26 points and 13 rebounds, and Pauly outplayed Caldwell, scoring 21 points on 9-for-14 shooting with six boards. Caldwell made only 6 of 19 shots and finished with 17 points. Baker had 15 points and Peters 14 for the Beavers.

“Caldwell had never experienced anyone guarding him like Steve,” Peters says. “Joe had great athletic ability, but so did Steve. Slats had us fired up. He mentioned Caldwell’s name until we were sick of hearing it. Steve was absolutely magnificent.”

“Caldwell would take off from the foul line and dunk it,” Counts says. “He had the same kind of springs as Michael Jordan. Pauly, with help from Gary Rossi, never let him get off. That was the key to our win. Slats had a plan. It worked.”

Says Baker: “It was the last fun game we had that year.”

It brought Oregon State to the Final Four, which wasn’t nearly the extravaganza it is today. It wasn’t even called “The Final Four” then.

“I had no idea what the Final Four was,” Peters says. “All I knew was we were in a big tournament.”

Every OSU player got two tickets for each game. Peters says he went around and collected those tickets from his teammates.

“They didn’t know what to do with them,” Peters says. “I had Ropesole (trainer Bill Robertson) sell them for me. I made $2,300. I went out and bought an engagement ring with it. I’m here today with my daughter and granddaughter. If I hadn’t sold the tickets, they wouldn’t be here.”

Cincinnati, led by future NBA players Tom Thacker, George Wilson and Ron Bonham, were the Beavers’ semifinal foe. The Bearcats were ranked No. 1. The Final Four games were played in Louisville’s Freedom Hall, capacity 19,000. All of the former Beavers have a similar distinct memory of the atmosphere.

“They allowed smoking in that arena back then,” Kraus says. “You looked up, there was smoke everywhere.”

“There was a big haze, because you could smoke cigars,” Peters says. “It was a different world.”

Oregon State hung with Cincinnati for a half, trailing 30-27 at the break. Then the bottom fell out. The Bearcats outscored the Beavers 53-19 in the second half to win 80-46. What happened?

“I’d like to know,” Pauly says. “It was a combination of things. Cincinnati was really quick. The further you go in the tournament, players are going to be quicker, jump higher and play better defense.”

In the opening minutes of the second half, Baker got picked clean three times for layups at the other end.

It was a terrible night for Baker, who was 0 for 9 and went scoreless, probably for the only time in his career.

“Terry had the flu,” Peters says. “Nobody knew it. I didn’t hear about it until later.”

“I was burned out totally,” says Baker, gassed from long back-to-back seasons in football and basketball. “I just didn’t have anything left in the tank. Couldn’t sleep, had stomach problems.”

It wasn’t just Baker. Oregon State shot .288 from the field. Counts was 8 for 14 and had 20 points and nine rebounds. The rest of the team was 9 for 45 (.200).

In those years, a third-place game was staged. Oregon State’s opponent was No. 2-ranked Duke, led by future pros Art Heyman and Jeff Mullins. The Blue Devils breezed to an 85-63 victory as the Beavers shot .287 from the field. Counts finished with 25 points and 18 boards but was 9 for 30 from the field.

“It wasn’t a good ending,” Baker says. “We didn’t do our best there. We could have done better.

“I’d love to have had a chance to do that all over again. We weren’t quite prepared for what to expect. We didn’t have any real scouting. To me it helps to know what you’re dealing with. That wasn’t Slats’ way. I’m not sure there was extensive scouting done by anybody in that era.”

Loyola of Chicago pulled off a big upset in the final, beating Cincinnati 60-58 for the national title.

Despite the disappointing game performances, reaching the Final Four was an achievement Oregon State’s players remain proud of.

“It wasn’t like a Final Four is today, but it was still an exciting time,” Baker says. “We were all thrilled to be there.”

“It was a good experience,” Pauly says. “I won’t say it wasn’t, even though we lost. It’s no fun to lose, but I don’t look at it as a bad experience.”

“My regret is, we didn’t win a national championship,” says Counts, who led the NCAA Tournament in scoring that year with 123 points in five games. “On the other hand, we were one of four teams still standing. That’s not bad.”

► ◄

The last three seasons of Gill’s storied career were great ones. Over that time, playing as an independent in between membership in the Pacific Coast Conference and the short-term AAWU, Oregon State went 71-18, making the NCAA Tournament all three years. That included one Elite Eight and one Final Four.

The 1961-62 team, led by Counts and Carty, was 24-5 and got to the Elite Eight before being knocked out by UCLA. The 1963-64 team was 25-4 — 25-3 before losing 61-57 to Seattle U. in a first-round NCAA Tournament game at Eugene. It was the final game of Gill’s career and left him at 599 wins.

“Jarvis and I still have nightmares about that,” Peters says. “We got caught off-guard that night. Jarvis and I fouled out. It was the only time I fouled out in my career.”

Had the Beavers beaten Seattle, they would have advanced to a Sweet Sixteen matchup with UCLA at Gill Coliseum. The Bruins went 30-0 that season and won the first NCAA championship under John Wooden.

“That was the biggest disappointment in my whole athletic career,” Jarvis says. “UCLA’s center (Fred Slaughter) was 6-5. He couldn’t have checked Mel. Frank and I matched up pretty well with Gail Goodrich and Walt Hazzard. We could have won and gone on.”

That OSU team featured Counts as a senior, Jarvis and Peters as juniors and Eaton as a sophomore.

“I think we were better that year than we were the Final Four year,” Peters says. “Counts had matured and Jarvis went from being a sophomore to a great player. Jim and I played really well together in the backcourt. I was a garbage man and Jim was a pure basketball player. Eaton was a terrific athlete who could rebound and play defense.”

It was the 1962-63 team, though, that got to the Final Four. No Beaver team has done it since.

“I’ve told umpteen people what a great group of guys we had,” Baker says. “A couple of us became lawyers. Pauly was a dentist. Torgerson had a PhD. Go down the line — special people. You’re not going to see a college team with that kind of people on it very often.”

I’ll give “The Flake” the final word.

“I really enjoyed our reunion,” Peters says. “I had forgotten how special the guys we had on that team were. No prima donnas. The only questionable guy was me, and I’m reformed — at least temporarily.”

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.