Sports books to consider…

(besides ‘Scrolls of a Sports Scribe’)

(To make it easy for you to buy any of these books if you are interested, I made each image linked to buying the book right on amazon.com or bookshop.org. I do get a commission if you use the links in this post.)

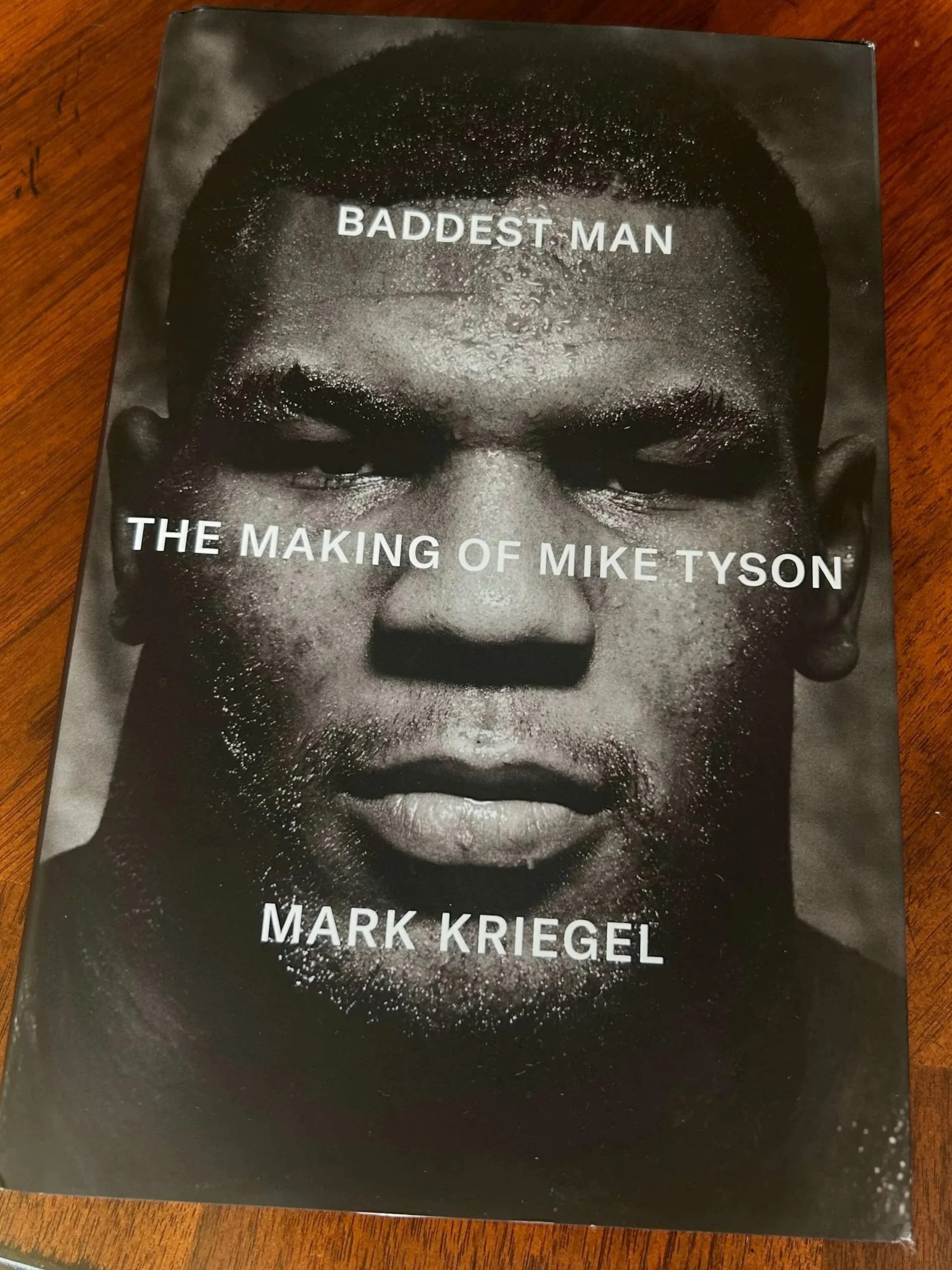

Baddest Man: The Making of Mike Tyson

By Mark Kriegel

Penguin Press (2025)

There are quite a few Mike Tyson books out there, including his autobiography, “Undisputed Truth,” published in 2014. The only one I have read is the newest one, “Baddest Man,” which I am pretty sure is the best one.

I remember Kriegel as a sportswriter for the New York Daily News and New York Post in the 1990s. He was a quality writer and columnist, especially on the sport of boxing.

And “Baddest Man” is an excellent book, taking us through Tyson’s journey of almost impossible obstacles during a dysfunctional childhood to becoming undisputed world heavyweight boxing champion from 1987-90.

Actually, Kriegel covers only the period through 1988 and Tyson’s showdown with Michael Spinks, who had beaten then-heavyweight champion Larry Holmes in 1985, then had the title taken away because he elected to fight Gerry Cooney rather than IBF No. 1 contender Tony Tucker. Tyson took a minute and 31 seconds to knock out Spinks and run his professional record to 35-0 at age 22.

Kriegel uses 380 pages to tell Tyson’s life story through his first 22 years, beginning in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. It is a fascinating essay of a survivor and a paradox — a savage beast in the ring, a two-bit thug out of it, but also with a side to his personality that was soft and vulnerable.

It is an unauthorized book, sort of; Tyson had lengthy conversations with Kriegel twice, the second with Tyson’s current wife, Kiki, also participating. Tyson, 56, may not have liked Kriegel writing a book about him, “but we did reach a functional understanding,” Kriegel writes in his acknowledgements. “He let me do my work unencumbered.”

Kriegel had plenty of background on Tyson from his years writing boxing in New York City, and he gathered more from interviews with dozens of people close to Tyson from childhood to his early years as a pro. Cus D’Amato died in 1985, but Kriegel learned enough from those who were around the veteran trainer to gain important perspective on the man who became a father figure in Tyson’s teenage years.

There is considerable insight from such insiders as Jose Torres, Bill Cayton, Kevin Rooney, Teddy Atlas and Jimmy Jacobs along with many fighters who fell victim of Tyson’s lethal punch on his way up the ladder to the world title. Most of them were scared to death to get in the ring with him.

“Mike had the reputation of being a young killer,” said Henry Tillman, the 1984 Olympic champion who beat Tyson twice as an amateur. “Everybody feared him.”

I found it fascinating to read about D’Amato introducing Tyson to hypnosis, filling him with positive thoughts and an air of invincibility. When Tyson was fully under the hypnotist’s spell, D’Amato would take over, saying such things to his disciple as, “You’re the best fighter that God has created. You are ferocious. Your intention is to inflict as much pain as possible. Your intention is to push (the opponent’s) nose into the back of his head. You throw punches with bad intentions.”

Said Tyson: “Sometimes Cus would wake me up in the middle of the night and do his suggestions. Sometimes he didn’t even have to talk. I could feel his words coming through my mind telepathically. Cus was my God … I can barely spell my name, but I think I’m a f-ing Superman.”

Kriegel’s writing style is conversational and easy to read. It left me wanting for more. He is working on a second Tyson book, this one covering the rest of Tyson’s life. Sign me up for a copy.

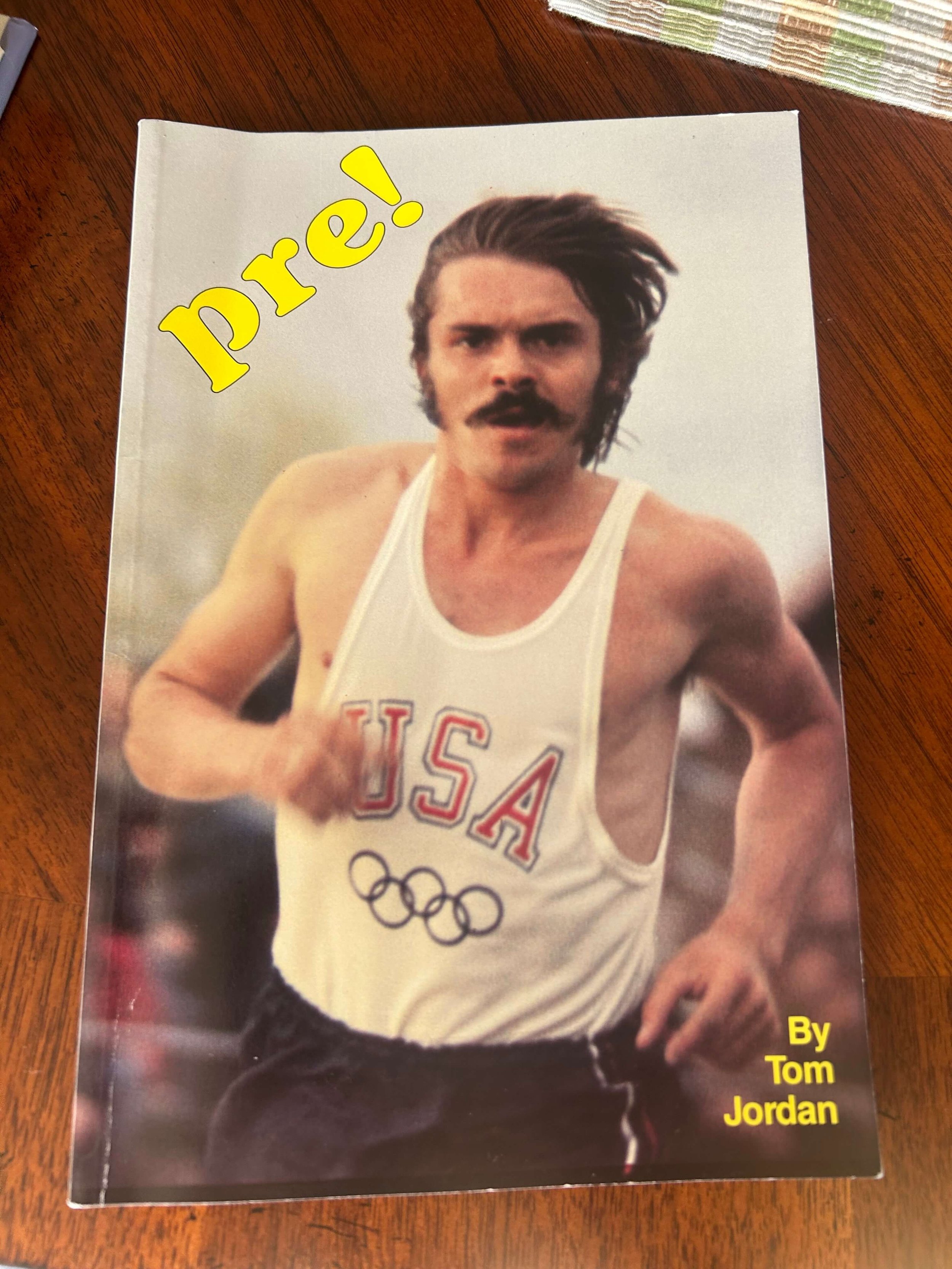

By Tom Jordan (1977)

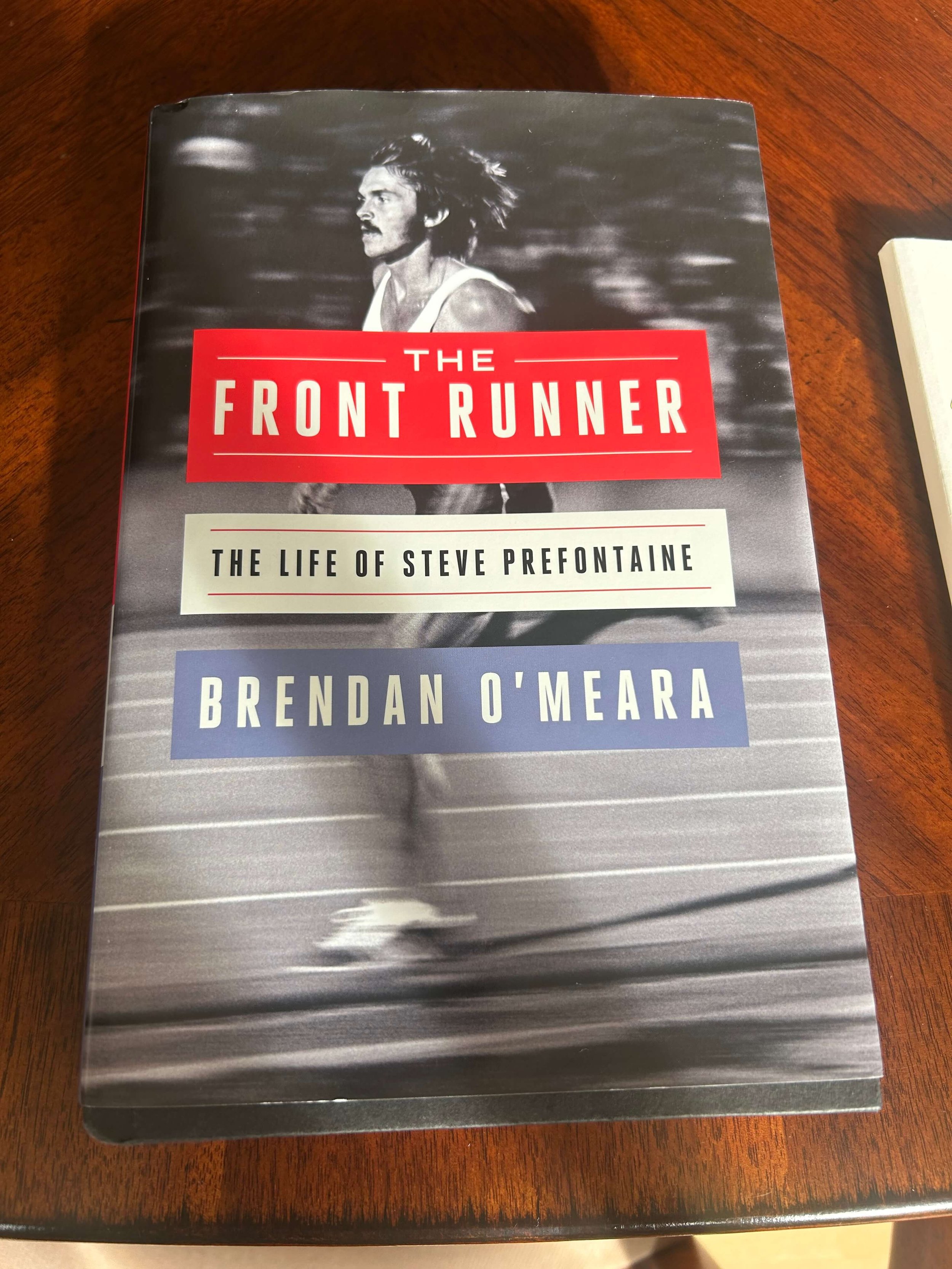

By Brendan O’Meara

Mariner Books

These are two books on the same subject — the great distance runner Steve Prefontaine — published nearly a half-century apart.

The first book was released two years after Prefontaine died in an automobile accident in Eugene at age 24. It is a thin book, 126 pages in length, with 60 photos illustrating the story of Pre’s short but illustrious career.

Jordan was a Track & Field News writer at the time, living in Palo Alto, Calif. He later moved to Eugene and served 37 years as meet director for the hallowed Prefontaine Classic, the nation’s best annual invitational. Jordan is a fantastic guy, a solid writer and was a top-rate meet promoter before his retirement a few years ago.

At the end of the foreword, Jordan writes, “It is my hope that someone else, closer to him personally and to his roots, will tell this story of Steve Prefontaine in some future book.”

That happened — sort of. O’Meara’s biography says he resides in Oregon, but he never met Prefontaine and likely wasn’t alive when the legendary Duck died in 1975. Published in the 50th anniversary year of Pre’s death, O’Meara’s book is a more complete, 277-page capsule of both the runner’s life and career.

Jordan did a nice job of interviewing the folks important in Pre’s running career, especially with UO cohorts Paul Geis and Pat Tyson and former coaches Walt McClure (Marshfield High in Coos Bay) and Bill Bowerman and Bill Dellinger (Oregon). Other interviewees included UO trainer Larry Standifer, teammates Mac Wilkins, Scott Daggatt, Steve Bence, Dave Taylor, Mark Feig and Lars Kaupang and national and international competitors such as Jim Ryun, Gerry Lindgren, Garry Bjorklund, Frank Shorter, Greg Fredericks, Don Kardong, Nick Rose, Dick Buerkle and Steve Stageberg.

O’Meara got to a number of those same people, plus UO shot putter Pete Shmock, Dave Wottle, Kenny Moore, Dan Fouts (the quarterback was at Oregon at the same time as Pre and they were friends) and several of those who knew him during his childhood growing up in Coos Bay. The author also relied heavily on previously published comments from many others, as you will find if you pore through 32 pages of notes in the bibliography.

O’Meara goes into greater detail in most aspects of Pre’s life. I particularly enjoyed his account of the 5,000 final in the 1972 Olympic Games at Munich, nine riveting pages taking the reader through a race in which the 22-year-old Prefontaine finished fourth behind Lasse Viren, Mohammed Gammoudi and Ian Stewart. Pre knew his better racing days were ahead, but his disappointment was intense, and O’Meara made it palpable with the reader.

I had read nothing before about Steve’s difficult and abused childhood. O’Meara writes that as a youth, Pre was beaten by his father, Ray, sometimes at the urging of his stepmother, Elfriede. The source: Steve’s half-sister, Neta, who said she was also beaten, and cousin Ray Arndt. Writes the author: “While it is a stretch to connect a straight line from being beaten as a child to Steve then wanting to ‘abuse’ the competition (on the track), the pain he endured at the hand of his father was, without question, a condition of his upbringing, in the same way that the pervasive culture of masculinity endemic to Coos Bay was an ingredient to the roundness of Steve’s character and burgeoning sense of self.”

Steve Prefontaine’s death was tragic and his life short, but it was full of relationships and accomplishments. Pre’s legend lives on, and these books rekindle memories of what was, and wonder about what could have been.

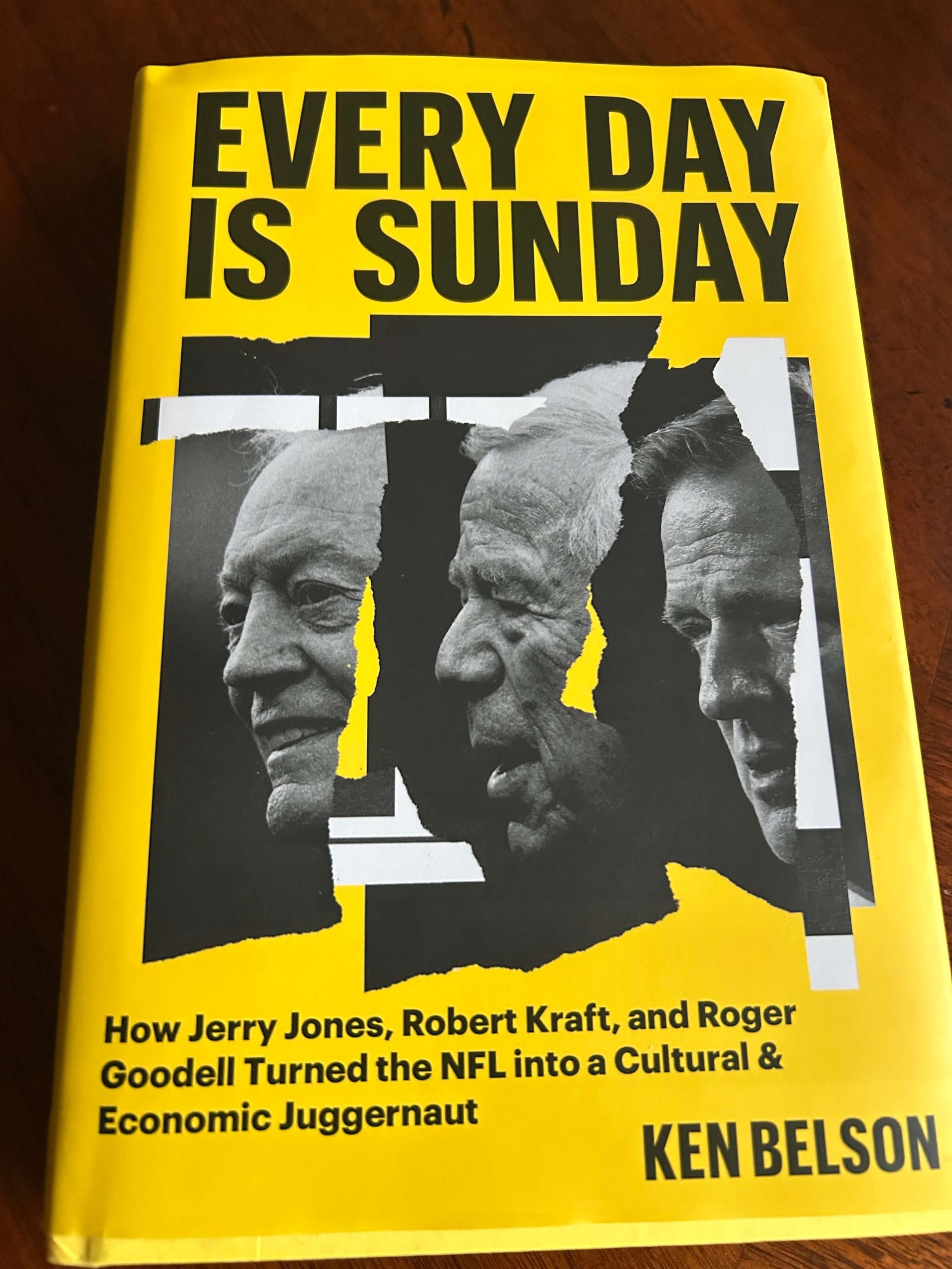

By Ken Belson

Grand Central Press

This book’s sub-title is “How Jerry Jones, Robert Kraft and Roger Goodell turned the NFL into a cultural & economic juggernaut.” Reading that, I wasn’t sure how much interest I would have in it. Seemed like a “Front Office Sports”-like production that might be pretty dry.

I enjoyed the read more than I thought. There are mini-profiles on Jones, Kraft and Goodell, with information some of which the author had gleaned from other sources but also some inside stuff he gathered from personal interviews with each.

Belson worked 14 years in the New York Times sports department, covering, among other things, NFL business news. He had access to the movers and shakers in the league and put it to use for the book.

The author is no shill for the NFL. He provides plenty of colorful stuff about the various franchise owners, including Jones of the Cowboys and Kraft of the Patriots, conveying that few of them lack for ego.

A great line by Belson: “Jones is known for his circular references, allergic reaction to punctuation and folksy idioms.”

The author starts with the beginning of free agency in the NFL in 1993. Running back Freeman McNeil was the key figure in the Players Association lawsuit that spurred action, though he retired following the 1992 season after a dozen NFL seasons, all with the Jets. (Funny how his name is not synonymous with free agency in the way that Curt Flood’s is in baseball.)

Fox and Rupert Murdoch soon came into the picture, winning NFC rights in 1994 for a staggering $1.58 billion. Murdoch also hired John Madden at $30 million over four years, among other big name broadcasters. Jones called the Fox deal a watershed moment for the NFL.”

The author covers the ensuing 30-year period of the league’s incredible financial growth. When Shad Khan purchased majority interest in the Jaguars in 2010 (the total sale price was $770 million), Jones told him NFL franchises would soon go for more than $1 billion. “I was like, ‘OK, Jerry, you can stop exaggerating now,’ ” Khan says.

By 2024, the Jaguars — located in Jacksonville, one of the NFL’s smallest markets — was valued at $4.6 billion. The Commanders sold in 2023 for an estimated $6 billion. According to Forbes, the average NFL team in 2023 was worth $5.1 billion, almost twice that of franchises in the NBA, the next most valuable sports league.

During Paul Tagliabue’s 17 years as commissioner, the league doubled in revenue to $8 billion by the time he retired in 2006 and was succeeded by Goodell. In 2024, net revenue stood at more than $23 billion. Under Goodell’s guidance, NFL media rights deals grew to a collective $25 billion in 2023. “He’s more of a political than a CEO,” an executive tells Belson, who writes that “the NFL has grown as large as a Fortune 500 company.”

In 1994, teams had up to $34.6 million to pay for player salaries. By 2025, teams had $279.2 million to spend on them, a jump of more than 800 percent.

Belson takes an honest look at controversies and issues the league has faced during the Goodell era, There are chapters on gambling, the 2011 lockout, the Colin Kaepernick-led kneel-downs, the sorry legacies of owners Jerry Richardson and Dan Snyder, concussions and CTE and the NFL’s pathetic $765 million payout to former players with ALS, Alzheimer’s and other diseases in 2015.

“Each team would pay about $24 million over the life of the 65-year settlement, and insurance would pay for part of that,” Belson writes. “It was the NFL at its most bloodless, sidestepping a major controversy by throwing money at a problem.”

Belson covers the move of the Chargers, the Rams and the Raiders to Los Angeles (and eventually the Raiders to Las Vegas).

“Fans in Oakland, San Diego and St. Louis were tossed aside so the owner could make even more money,” he writes. “Oakland and St. Louis spent hundreds of millions of dollars to help their NFL teams only to see them leave.”

Belson also provides an inside look at the annual owners’ meetings through a secret audio tape of a three-hour meeting obtained by the New York Times. There were cliques and rivalries; owners sometimes had lower-level executives save seats for them close to their buddies or in the vicinity of Goodell.

“What did they care if an assistant lost an hour of sleep?” the author writes. “Billionaires are used to having others doing things for them.”

More than anything, with NFL owners, it is about the money, Belson writes. It’s always about the money.

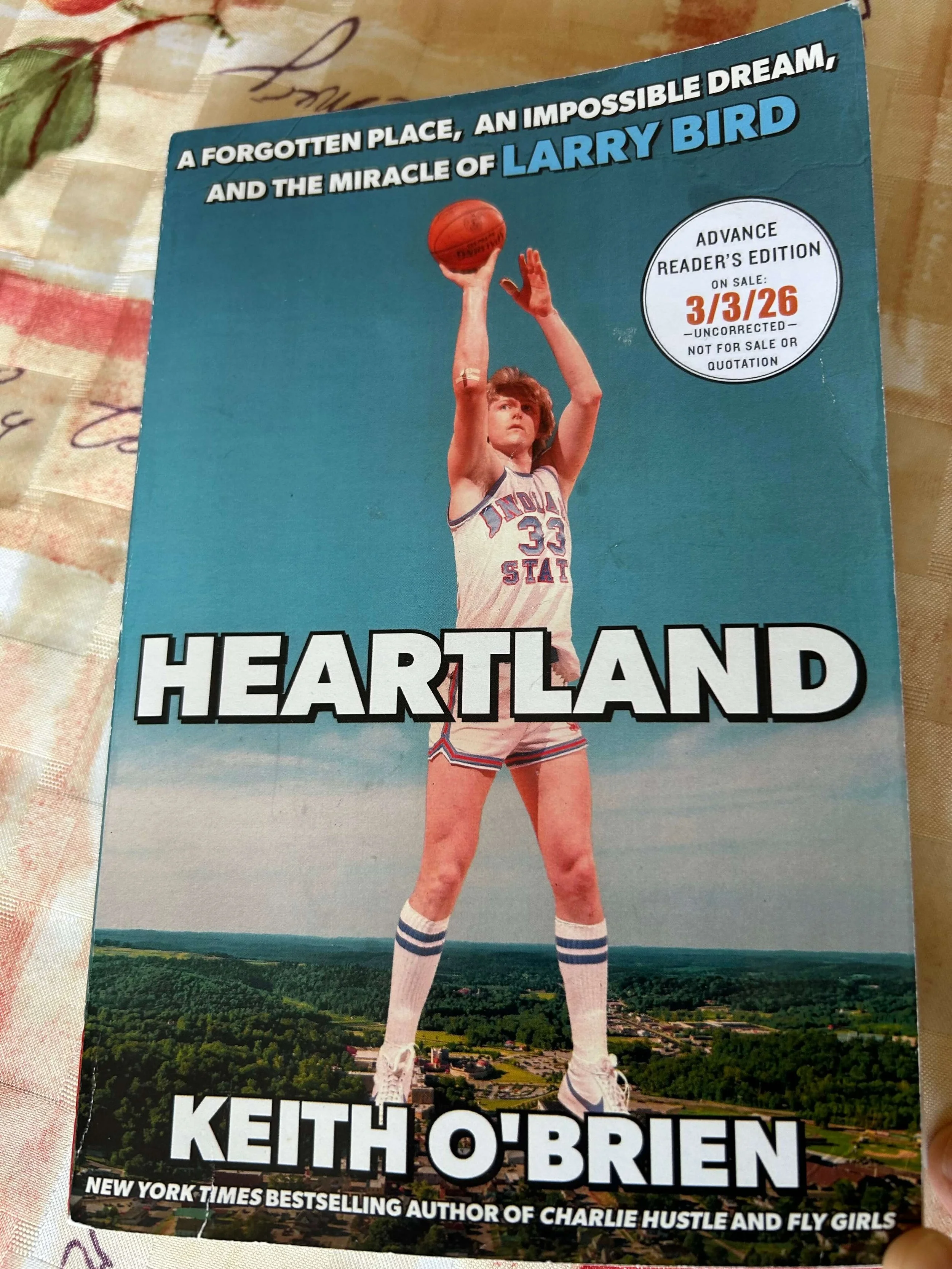

Heartland: A Forgotten Place, an Impossible Dream and the Miracle of Larry Bird (2026)

There have been a bunch of books written about Larry Bird, including ones penned by legendary Boston writers Bob Ryan (1989), Jackie McMullen (2000) and Dan Shaughnessy (2021). I’ve not read any of them, but I’m guessing they focused on his post-collegiate playing career with the Celtics and, at least in McMullen’s book, on Bird’s three-year stint as coach of the Indiana Pacers.

This book by the New York Times’ O’Brien shines the spotlight on Bird’s life from childhood until his junior year at Indiana State, when he led the Sycamores to perhaps the most surprising run to the NCAA championship game in history. It’s unauthorized — Bird declined to participate — but the author interviews many of those around him during those years, including high school and college coaches and teammates.

Covered are Bird’s underprivileged childhood growing up in rural French Lick, Ind., his father’s suicide, a marriage before his 19th birthday and a daughter from the short union, all of which he is reluctant to discuss with anyone. O’Brien stresses that Bird spent only three weeks at the University of Indiana not because of disdain for volatile coach Bobby Knight but because he felt overwhelmed by the enormity of the campus and school in Bloomington.

The book is well-researched and has some interesting nuggets, such as this: In 1977, the Indiana State and Evansville teams used the same DC-3 to charter flights for road trips. Flying the same plane the Sycamores were to use three days later, Evansville’s plane went down in bad weather outside of Indianapolis, killing all 29 passengers and crew members.

O’Brien accurately describes Bird’s distaste for interviews and the media, which he carried with him through his pro career. I covered the league during his final three NBA seasons and he was pretty much unapproachable. In college, the excuse was he was a private person who didn’t like anybody prying into his business. The idea of being a public figure never resonated with him. By the time he got to the end of his NBA career, he had decided he just didn’t want to deal with media, unless they were hometown reporters such as Ryan, McMullen. Shaughnessy, Steve Bulpett and Peter May.

There is some good stuff about the beginning of Bird’s strong relationship with Magic Johnson, with whom he would meet up when Indiana State and Michigan State collided in the 1979 national championship game. They were as unlike as possible in personality — Johnson loved the media and being in the spotlight — but both were driven, and work ethic helped get them to the top.

I found a lot of the book interesting — a good compilation of information about the formative years of one of basketball’s all-time greats. My review copy arrived well in advance of the book’s release on March 3. After that date, it will be available wherever books are sold. If you are a Bird and/or Celtics fan, it is worth the read.